Introduction

The Republic of Moldova declared its independence from the USSR on August 27, 1991. However, Russian forces have remained on Moldovan territory east of the Dniester River supporting the breakaway region of Transnistria, composed of a Slavic majority population (mostly Ukrainians and Russians), but with a sizable ethnic Moldovan minority. According to the 1989 census, the population of Transnistria was composed of about 40% ethnic Moldovans, 28% Ukrainians, and 25% Russians. In 2004, the authorities of the breakaway region took another census, but the results are disputed due to a lack of transparency of the process. At the current time, we can assess that the breakaway region strives not to be part of Moldovan media space. The broadcasts from the right bank of the Dniester are jammed, and the frequencies of Moldova TV broadcasters have been redistributed to rebroadcast Russian content.

This report does not cover the breakaway region of Transnistria, as it presents a different model and structure of the media landscape, oriented towards pro-Kremlin narratives and direct ‘state’ support of controlled media outlets. Also, there is a lack of reliable data on media consumption trends as well as a real connection to the Moldovan media market.

Regarding the social structure of Moldova, data from the last census states that over 82% of the population is Moldovan/Romanian speakers. The other ethnic groups are categorised under the artificial ethnolinguistic term ‘Russian speakers’. This is reminiscent of the Soviet period when the interaction between different ethnic groups was through the Russian language. This makes them more vulnerable towards manipulation, as they are prone to consume media products coming from the Russian Federation as well as local products aimed at them. For example, the sputnik.md website, a satellite website with connections to Russian power structures, publishes most of its content in Russian and some in Romanian.

A high level of trust in the church is a constant of Moldovan society. According to the Opinion Barometer, over 70% of the population trusts the church, this being the highest level of trust in any social organisation. The Moldovan Metropolitanate has close ideological and economic relations with the Russian Federation, developing lucrative business models based on its exemption from income taxes. A recent investigation uncovered business ties to Russian companies selling votive candles at dumping prices to the Moldovan church. These ties, as well as the political activism of the church, makes it an active player that may be promoting foreign interests in Moldova. One of the experts interviewed within the research explains:

‘Since the declaration of independence of Moldova, the church has backed numerous candidates at every election in the parliament. Be it the Socialist Party or a former Secret Service director turned politician. The church had close ties with the Communist Party when it was in power and … is promoting interests close to the Russian Federation’.

The country signed and ratified an Association Agreement with the EU in 2014, which fully entered into force in July 2016 after ratification by all EU member states. Currently, the parliament of the Republic of Moldova is dominated by an alliance of the Democrat Party and the European People’s Party of Moldova, the government is composed almost exclusively from representatives of the Democrats. In November 2016, Igor Dodon, the leader of the pro-Kremlin Socialists Party, became the president of the Republic of Moldova and promotes closer ties with the Russian Federation and the revision of the Association Agreement with the EU. According to one of the experts, the very existence of the Socialists Party poses risks to national information security:

‘Compared to Ukraine, the Republic of Moldova presents a worse political situation in the relationship with pro-Kremlin propaganda. The Ukrainians have banned the pro-Russia Regions Party, and we still have the Socialists Party. Together with President Igor Dodon and the affiliated media holding they represent the key threat to our information security’.

From an economic standpoint, Moldova remains Europe’s most impoverished economy. In 2014, 1 billion USD was stolen from three Moldovan banks: Banca de Economii, Unibank, and Banca Sociala. The theft had a political component with the implication of the former prime minister, Vlad Filat, who was sentenced in the case, as well as other high-level officials. As one of our anonymous respondents put it,

‘poverty is an important factor in the sensitivity to propaganda, as a person striving to feed oneself will not have the time to consume media content, and if one does, it will not be quality content’.

In 2015, protests erupted in the capital Chisinau with participants claiming that all the governing parties had been involved in the theft of the 1 billion USD, asking for early elections. The left pro-Kremlin parties, as well as right extra-parliamentary opposition, have used this narrative both in national and local elections since that period.

While the EU has become the most significant trading partner of Moldova, with over $3.5 billion in overall trade, Russia remains one of the most significant destinations for Moldovan economic migrants. Also, the Russian market is the second biggest export destination for Moldovan goods with over 11% of total exports for the first quarter of 2017. Another big issue is the country’s energy dependency on Russian energy resources and over 6 billion USD of debt accumulated by the country, including the Transnistrian region.

Vulnerable Groups

The groups which are more susceptible to manipulation through mass media than the population in general are ethnic minorities that must consume Russian media products, Orthodox churchgoers, and the elderly. These groups have limited access to alternative media to check facts and they trust media channels that can be used for manipulation.

The Republic of Moldova presents an ethnic diversity common in most post-Soviet countries, with some local peculiarities. According to the last census in 2014, 75.1% of the population was declared Moldovan, Romanians were 7.0 %, Ukrainians, 6.6%, Gagauz people, 4.6%, Russians, 4.1%, Bulgarians, 1.9%, Roma, 0.3%, and other ethnicities, 0.5%.

Compared to the last census, the share of the population that identify themselves as Moldovans decreased by 10 percentage points (pp), and those who declared themselves Romanian rose by 4.8 pp. In the last 10 years, the percentage of those with Russian and Ukrainian ethnicity decreased by 1.9 and 1.8 pp, respectively, and the percentage of ethnic Bulgarian, Gagauz people, and Roma people did not change.

There is still an ideological differentiation between the ethnopolitical terms Moldovan and Romanian. The ‘two’ languages are the same, a fact confirmed even by the Constitutional Court of Moldova, but some politicians use the ‘Moldovan’ narrative as an argument against closer relationships with Romania, NATO, and the EU. Another issue with ethnic diversity policies in the Republic of Moldova is that for an extended period all of the minority ethnic groups have been treated as ‘Russian speakers’ in the educational system and media outreach. Rather than translating legislation into all the minority languages, the state has decided to present it to the public in only Romanian and Russian. At the same time, all the minority language schools in the Republic of Moldova have Russian as the primary language and the minority language as the secondary one.

The language question is a painful one in most ex-Soviet countries, and legislators avoid regulating it outright to prevent provoking a social backlash. At the same time, this has created a situation in which most of the ethnic minority representatives speak their native language and Russian equally, rather than the state language. Moreover, final exams in the Moldovan/Romanian language have in the past caused conflict, for example, between the Moldovan authorities and the leadership of the Gagauz Autonomous Region, which threatened to issue parallel high school diplomas for those who failed them. Thus, by choosing not to deal with the issue of promoting minority languages but rather adopt Russian as a proxy language, the state has led most ethnic minorities to consume media mostly in Russian. This is reflected in voting options as well. The northern districts, densely populated by Ukrainians and people in the Gagauz Autonomous Region, seem to favour pro-Kremlin candidates, both in local and national elections. Based on these factors, we can safely conclude that the Ukrainians and Gagauz people are highly vulnerable to pro-Kremlin propaganda.

Another group sensitive to pro-Kremlin propaganda is the close followers of the Moldovan Orthodox Church, which is under the authority of the Russian Orthodox Church. Hundreds of zealots protested against an equal rights law in 2013, claiming it was the first step to legalising same-sex marriages. The law merely guaranteed protection against discrimination in working relationships. Most of the protesters declared that they were blessed by the head of the Church to participate and would do it again if asked. While 90.13% of the population of the Republic of Moldova claim to be Orthodox, most are not ardent followers. At the same time, a significant number of frequent churchgoers can be influenced by narratives promoted by the Church.

A third group sensitive to media manipulation is the elderly. According to official data, more than 718 000 Moldovans are retired. The media literacy of this category of people is more limited than the general population, as are their internet skills. They rely on traditional sources of information and informal communication to get news. Also, their limited income does not allow them to buy newspapers or magazines. This is exploited by parties that produce papers and distribute them free of charge. Often these publications promote fake news, such as a story about 30 000 Syrian refugees who were supposed to come to Moldova if the pro-Western candidate, Maia Sandu, was elected president. This type of media is hard to track, as many of them do not indicate the number of issues or the authors of the articles they print. One of the interviewed experts stresses the vulnerability of the elderly to media propaganda and disinformation this way:

‘The elderly, especially in rural regions, have a tougher time distinguishing between propaganda and actual information. While the younger generation may use alternative sources from the web, the older people are “bombarded” by Russian and local propaganda. The media education projects should target them for sure”.

According to the last Opinion Barometer (April 2017), over 60% of people older than 60 would vote for joining the Russia-led Eurasian Union. For comparison, from the 18-29 age group, only 36% would vote for the same. One explanation for this situation could be Soviet nostalgia, widely present among older people.

Media Landscape

According to the 2016 Freedom of the Press Index, Moldova is partly free. In March 2015, parliament provided the legal background to require TV and radio companies to disclose their final beneficiaries, as well as board members, managers, broadcasters, and producers. The national authorities have also used national-security reasons to bar several Russian journalists from entering Moldova, declaring them ‘undesirable persons’.

In the Reporters without Borders ranking, Moldova in the 2017 World Press Freedom Index ranked 80th, falling four places compared to 2016. The organisation assesses the Moldovan media market to be diversified but also incredibly polarised. It points out that the editorial positions of the media outlets depend on the interests of their owners or affiliated politicians. An important issue in the media climate is the lack of independence of the broadcasting regulatory authority.

The IREX Media Sustainability Index gave Moldova a 2.3 (out of 4) in 2017, comparable to the 2016 score and placing it at the ‘near sustainability level’. The index emphasizes problems with the independence of the Broadcasting Coordination Council (BCC), media ownership, and access to information for journalists. These problems persist, especially in the justice system, which tries to anonymise decisions based on data-protection principles while looking to make it harder to investigate corruption cases.

The EU-funded Media Freedom Watchproject’s ranking of the Eastern Partnership countries (Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan) states that Moldova has made significant progress regarding guaranteeing media freedom. This leads to the conclusion that the press in Moldova is relatively free by most accepted standards.

The BCC register includes 126 programme services, including:

70 television stations:

- 32 broadcast via terrestrial channels, including four satellite channels,

- 31 distributed only via cable networks; and,

- 7 broadcast exclusively on satellite.

56 radio stations:

- 55 broadcast via terrestrial frequencies, including one through satellite;

- 1 through wired diffusion.

According to the list published by the BCC on its website, of the 70 television stations, five have national coverage: Moldova 1, Prime, Canal 2, Canal 3, and Publika TV. Of the 56 radio stations, eight have national coverage: Radio Moldova, FM Radio, Publika FM, Radio Plai, Hit FM, Vocea Basarabiei, Fresh FM, and Noroc Radio.

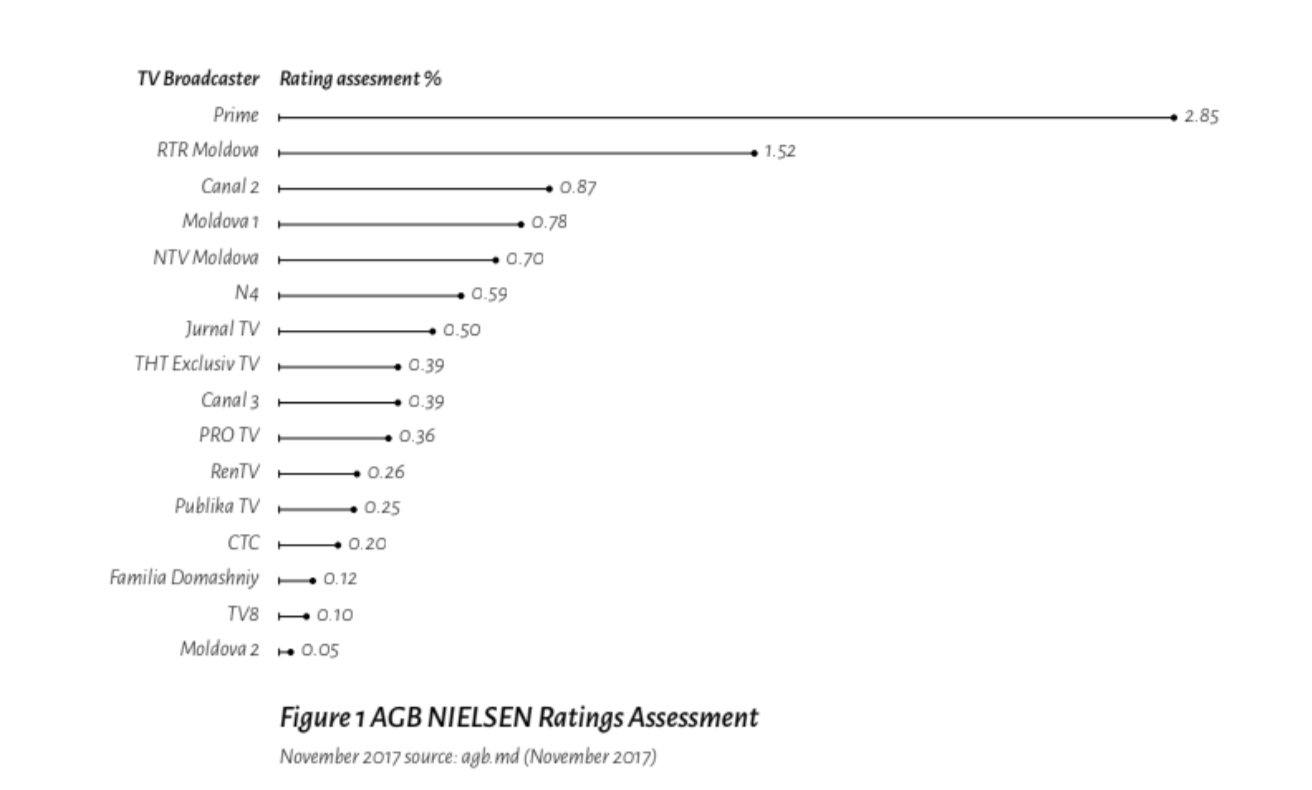

An audience measurement of television stations in the Republic of Moldova was carried out under the aegis of AGB Nielsen Media Research by TV MR MLD. Some broadcasters and NGOs have questioned the independence and objectivity of the research and development of the results.

According to AGB data, in November 2017, Prime had the highest average daily audience, with a rating of 2.85%. RTR Moldova ranked second with 1.52%, while Canal 2 was ranked third with 0.87%. Four channels—Moldova 1, N4, NTV Moldova and JurnalTV—have average ratings ranging from 0.78% to 0.50%, and the other eight stations have less than half a percentage point each in their respective rankings.

At least seven TV stations, including five of the top 10, rebroadcast Russian TV channels. These include Prime (ORT), RTR Moldova (RTR), NTV Moldova (NTV), TNT Bravo (TNT), Ren TV Moldova (REN TV), STS Mega (STC), and RenTV.

Experts point to the monopolisation of the media market as one of its challenges:

‘One of the biggest issues of the Moldovan media landscape is the monopolisation of the market … There are two main media “holdings” , one representing the government and governing party and another the president and the Socialists that promote manipulative content, both local and foreign … This multiplies the external factors’ effects tenfold’.

In general, Russian broadcasts dominate most of the top 15 TV channels, as shown by AGB measurement data for November 2017. Basically, for two-thirds of the top television channels (10 out of 15), the most watched are mostly broadcasts and programmes in Russian. They usually originate from Russian channels, Soviet-era production films, or TV series produced in Russia. The few exceptions are Moldova 1, Pro TV Chisinau, Publika TV, Realitatea TV, and, partly, Channel 2. Yet another concern is the specifics of the broadcasters’ business:

‘One of the biggest issues that promotes manipulative content is the business model of the broadcasters. Most of them are not profitable, but rather rely on obscure models of receiving money for promoting such narratives’.

An eight month study carried out in 2014 by the Electronic Press Association’s monitoring of eight television stations (Canal 2, Canal 3, JurnalTV, Moldova 1, Prime, Pro TV Chisinau, Publika TV, and TV7) also confirms the prevalence of Russian TV content. This study confirmed the prevalence of Russian TV content. Thus, two of the four private national broadcasters at peak hours transmitted Russian media products (other than artistic films) in a proportion of over 50% (Canal 3, 50%; Prime, 77%). At the same time, if we exclude movies, the programmes broadcast in Russian (including rebroadcasts) from the two television stations varies between 76% (Canal 3) and 80% (Prime).

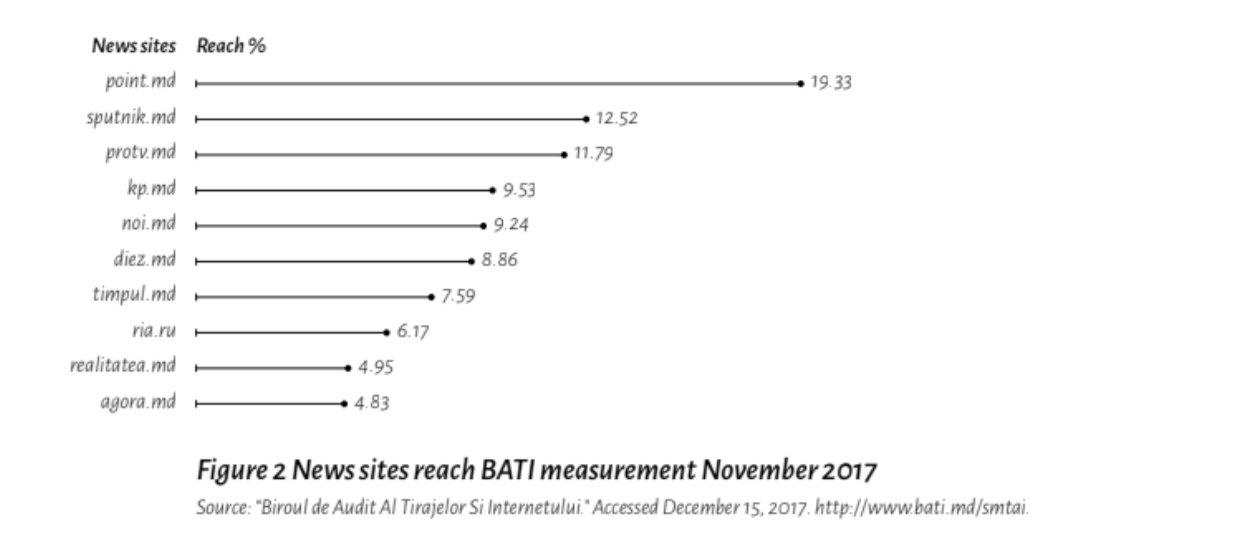

In relation to online media, the Audit Bureau of Circulations Moldova (BATI) issued the ratings shown in Figure 2 for October 2017. The ratings show that four out of the 10 most viewed news websites in Moldova, including the most popular site, point.md, promote pro-Kremlin positions. Furthermore, another top site also includes the Russian site ria.ru, which has a reach of over 6% of the population. The sister website of sputnik.ru, backed by the Russian government, Sputnik.md, has both Russian and Romanian versions to reach a bigger audience. Most of these sites were found to promote fake or manipulative news, according to local debunking initiatives.

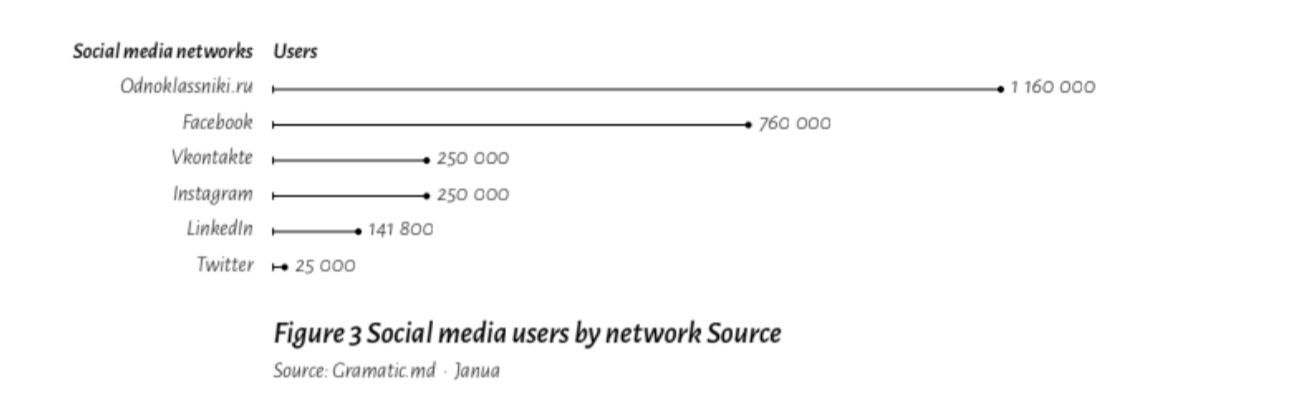

According to a report published by the digital communications agency Gramatic.md, the most popular social media network in Moldova is the Russian website Odnoklassniki.ru, with more than a million users. The Russian social media network Vkontakte ranks third, with more than 250 000 active users. The average profile of an Odnoklassniki user is a high school graduate (over 37%), who lives in the centre of the country (over 54%) and is 20-29 years old (over 31%).

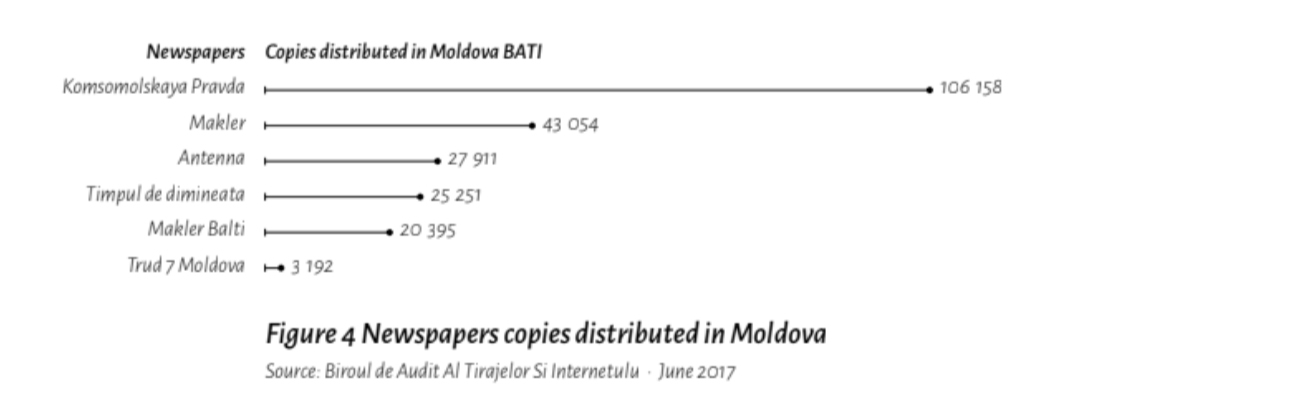

The newspaper business in the Republic of Moldova, as in most post-Soviet countries, is in decline, since many of the former consumers have switched to online versions of the same newspapers. The BATI statistics for June 2017 show there currently is only one daily newspaper, Komsomolskaya Pravda, which distributed more than 106 000 copies. The weekly publications’ statistics include two personal adverts newspapers, Makler and Makler Balti. There are also data on three other semi-major newspapers, Timpul de dimineață, with over 25 000 copies, Antenna, almost 28 000 copies, and Trud 7 Moldova, more than 3 000 copies. Only one of the newspapers on this list is published in Romanian. Two of the others, Komsomolskaya Pravda and Trud 7 Moldova, are known to take a position favourable to Kremlin narratives. Also, we must acknowledge that these distribution figures are voluntary and do not include local and party newspapers.

In the Republic of Moldova, the broadcasting domain began to be regulated in 1995, more than four years after the declaration of independence (1991), when the first ‘Law on broadcasting’ came into force, creating the BCC and empowering it with regulatory control and licensing functions.In the early years of the BCC, it approved numerous licenses for TV and radio broadcast without any limitations on content, including the language and provenance of materials.

In 2006, after the adoption of the new ‘Broadcasting Code’, the BCC elaborated a ‘National Territorial Coverage Strategy’ that has set some objectives for the promotion of national content and broadcasts in Romanian, which were significantly lagging the Russian-language content. According to one of the interviewed experts,

‘the adoption of the new “Broadcasting Code” has been in question since 2010. It was one of the issues stated in the Association Agenda with the EU. In order to have a strategic approach to fighting propaganda, this agreement should be fulfilled and translated into actions’.

Although the strategy was revised in 2011, its objectives of reaching 70% of broadcasts in the national language have yet to be met. So, from the analysis by AGB Nielsen Media Research, four out of the five most popular TV stations in the Republic of Moldova do not comply with the legal requirements. The schedules of Prime TV, RTR Moldova, NTV Moldova, and Channel 2 are widely dominated by Russian programmes and TV shows. Some of these present programmes acquired from Russian TV stations as ‘own productions’ due to the exclusive rights to rebroadcast on the territory of the Republic of Moldova. This loophole has not been closed by the BCC and is widely used to mask foreign media products as nationally produced while promoting the Russian propaganda agenda. Even entertainment products directly or subliminally support the interests of the Russian propaganda machine. This makes their domination over the Moldovan broadcasting market an avenue for disinformation and outright propaganda.

The Moldovan journalist community’s Press Council adopted the latest version of its deontological code in 2011. The document includes a series of rules for obtaining and processing information, as well as ensuring the accuracy and verifiability of the facts presented. Journalists must receive information from a minimum of two sources, quoting them when possible. The implementation of the code is the responsibility of the signatories. The journalists’ professional ethics committee is responsible for monitoring the implementation of the code. Nevertheless, the last published press release by this committee dates from 2008, and the website of the NGO community has been under reconstruction for a long time. This seems to be due to a lack of resources to continue the activity at even the low level of compliance within the code itself. Experts believe that the significance of the deontological code should be increased:

‘If you have local journalists who join international circles in promoting manipulative narratives, the community should step up and respond to it. While the fact-checking initiatives haven’t had it as easy as the “sexy” well-rounded arguments of fake stories, they should continue, as there is a clear need to debunk them’.

According to yet another expert,

‘I would compare the journalists to doctors who swear the Hippocratic oath and then ask for ‘gifts’ or money after the operations. We are a product of a society where moral rules without sanctions have little bearing. This is the problem with the deontological code’.

An adequate, sustainable system of self-monitoring in the media community relies on the availability of members who comply with the legal codes as well as the importance of ethical rules in the broader social context. Due to the structure of the Moldovan media landscape, it is unlikely that self-monitoring will have a high rate of compliance. A possible role for the application of the deontological code would be through ‘public shaming’ rather than implying a of journalist’s compliance with the respective norms. Nevertheless, the code has other positive functions, for example, the one made within the ‘Stop Fals!’ campaign, which refers to the code as upholding the standards of ‘good journalism’. Strengthening mechanisms monitoring the implementation of the deontological code could possibly enhance the capabilities to deal with propaganda and media manipulation.

Legal Regulation

The primary document that defines information security in the media dimension is the ‘National Security Strategy of the Republic of Moldova’, adopted by the Parliamentary Decision No.153 of July 15, 2011. Paragraph 47 states that challenges in the media sphere are part of the national security threats to the Republic of Moldova. In this respect, the strategy reported that the normative framework should be adjusted by the introduction of appropriate, active monitoring, control, and implementation mechanisms to protect Moldovan society from misinformation attempts and manipulative information from the outside. While capturing the essence of the issue, the strategy does not provide actionable and measurable outcomes and is limited to declarations of intent.

The law regarding the Information and Security Service (ISS) does not provide a clear framework for dealing with information security. The primary objectives of the agency are to deal with espionage, diversions, and other criminal offences from being attempted against national security. At the same time, most pro-Kremlin propaganda does not fall under the penal code and cannot be criminalised. The tools to monitor and limit foreign media influence are provided in Article 8 of the law, which states that the service can perform both information and counter-information activities. While the fight against foreign propaganda can fall under these two activities, it is not clear whether the service deals with these issues. According to the head of the Independent Press Association, Petru Macovei,

‘we should have a useful Information and Security Service able to monitor the financing of politicians and broadcasters. During the last presidential campaign, investigative journalists found schemes of offshore financing of broadcasters through the Bahamas, but the service chose not to act on it and “not to be effective”’.

An interesting initiative is the draft law No. 189 of June 13, 2017, proposed by the ruling Democrat Party. It puts forward a definition of information security that limits it to all measures to protect individuals, society, and the state from any attempts to propagate misinformation and manipulation from the outside. This definition describes with a reasonably high degree of accuracy two types of propagandistic activities, but it adds some uncertainty and contradicts the terms used in the ‘Information Security Concept’ drafted by the ISS and adopted by parliament.

Initially, it is worth mentioning that the set of measures described by project No. 189 refers to the state’s reaction to a range of potential security risks. Although useful, this concept cannot be considered ‘information security’, but instead, state policy to ensure information security. Further, by analysing the elements of hostile information activities described by the project, we note that two essential elements are reviewed: misinformation and manipulative information, which in the context of the definition, results in propaganda. In fact, researchers also distinguish between misinformation and misleading information, the latter being unintentional and, as a result, less prejudicial.

At the same time, this definition does not include propaganda activities that do not necessarily involve the output of erroneous information but the promotion of values and visions hostile to the Republic of Moldova, so-called ‘hostile narratives’. Also, there is the situation when two legislative drafts give an alternative definition to the term ‘information security’, so referring to the ‘Information Security Concept’ and the legislative draft No. 189 is not advisable.

In the Information and Security Service-promoted document, ‘information security’ is the state of protection of a person, the society, and country, which determines the ability to resist threats to confidentiality, integrity, and availability in the information space. This concept is used in the West to define cybersecurity and is part of a broader information-security umbrella. The problem is acknowledged by the interviewed experts:

‘There is a lack of consensus on the notion of “information security” and what the state should do about it. Moreover, I would say there is a lack of political will to effectively deal with this issue’.

There seems to be a lack of communication between the principal actors in national security policy in the Republic of Moldova and the non-alignment of draft normative acts in the same field. Also, both projects interpret ‘information security’ in a way limited to its sectoral aspects.

The only measure provided by draft law No. 189 is the introduction of a ban on the transmission of informational, informative, analytical, military, and political broadcasts from countries that have not ratified the European Convention on Transfrontier Television, except for the EU , the US, and Canada. One of the legal experts interviewed within this research says:

‘I have a more liberal view of the media market. There should be serious grounds on banning the rebroadcasting of some political views and they were not presented yet. If we are to fight propaganda, we should not use similar tools, but go after the final beneficiaries of media companies and ensuring transparency. The broadcasters should take their own obligations under the law more seriously’.

This measure, although easy to monitor, has several apparent shortcomings. Media agents may be re-registered in states that are signatories to the convention, or messages released in the broadcasts concerned may be modified for use in local broadcasts for formal compliance with the legal provisions. Also, the envisaged measures only affect broadcasting media and do not interfere with other media (print and online media, as well as the informal communication environment). In the case of developed propagandistic networks, the expected effect of the legislative changes will be short-term and will not affect the transmission of messages hostile to Moldova.

Another expert that we spoke to says the following:

‘This flagship initiative was speeded through a parliament’s hearing and adopted on the first and second reading during one day without respecting the norms on transparency and participation … Still, I consider that banning a TV broadcast should come through a court decision with respect for human rights’.

Another essential element of the legislative framework is the ability of the BCC to fight media manipulation. According to the ‘Broadcasting Code’,the BCC can license, suspend, or withdraw the licences of TV and radio stations, as well as fine them. Also, it can punish media outlets that promote propaganda narratives in cases when the information comprising the news is not accurate. Reality is distorted through montage tricks, comments, or titles. In some conflicts, the media outlet did not respect the principle of information from several sources.

While the three cases do not cover all the possible types of media manipulation, even these are used sparingly. Most of the circumstances found media outlets do not reflect reality. Instead, they use public warnings. A legal expert explains one of the reasons for the country’s vulnerability to foreign propaganda:

‘We have a public regulator of the media market that chronically fails to do its job. The situation with the Moldovan mass media is not a recent development. It functions just formally. It has become sterile. This is one of the causes of the fact that Moldova is one of the weakest states within the Eastern Partnership in terms of propaganda’.

For example, the monitoring of the campaign for the local referendum dismissing the mayor of Chisinau, Dorin Chirtoaca, caused the BCC to find irregularities in the news broadcast of five of the monitored TV stations. All received public warnings. This ‘slap on the wrist’ practice makes the existing mechanisms inefficient and favours impunity for media outlets promoting ‘fake news’.

Another issue with the current ‘Broadcasting Code’ is that the BCC does not have a clear mandate for monitoring broadcasts except during electoral periods. This can contribute to using it as a tool to ‘control’ the opposition press, as there is no certainty and predictability in the monitoring process:

‘The first problem of the BCC is that the nominations are highly politicised. It does not provide transparency in the decision-making process and does not require public hearings with the participation of civil society. This leads to politically motivated decisions like, for example, suspending the licence of the opposition TV station Jurnal TV’.

Another essential legislative act relevant to propaganda vulnerability is the ‘Law about the Press No. 243’, adopted on October 26, 1994. While it requests news agencies register with the Ministry of Justice, it does not make it compulsory and does not provide sanctions for failing to do so. The ministry could be, according to a representative of the Association of the Independent Press, a critical threshold for limiting the creation of ‘cloned’ news sites and deceiving ‘satire’ sites that promote propagandistic messages:

‘Many Russian entertainment TV shows and publications subtly promote pro-Kremlin narratives. This makes the efforts taken by the government less useful, as they target mostly political and military TV broadcasts’.

In principle, in the Republic of Moldova, there is no mandatory registration for the online press and any site owner can pose as representing mass media. In recent years, there has been a massive build-up of bloggers whose messages promote pro-Kremlin themes and favour the governing parties. Sometimes they are the sources of fake news or ‘leaks’ against the opposition:

‘Anyone with a limited amount of money could open up a website to promote fake news and get away with it. The legislation has no limits on it and no sanctions. I consider that there should be fines or other types of penalties for those who make it a profitable activity’.

The legislative framework of the Republic of Moldova is outdated and needs to be adjusted to the emerging threats to information security. But these efforts need to take a systemic approach, shaped by the updated ‘National Security Strategy’ to avoid legislative conflicts and provide sufficient mechanisms of control to ensure both adequate countermeasures and respect of freedom of the press.

Institutional Setup

The main actors dealing with media vulnerability in Moldova can be divided into three categories: state actors, civil society, and media outlets. Concerning the state actors, the following are critical players:

- Parliament, the representative of legislative power;

- The BCC, the primary regulator of the TV and radio markets;

- Ministry of Justice, the registrar of news agencies and newspapers;

- President, guarantor of national security; and

- The ISS, the body dealing with hostile information activities on the territory of the Republic of Moldova.

The reporting system in place has limited capacity for parliament to monitor the developments in media resilience effectively. Both the ISS and BCC report annually to parliament on general issues. They do not provide detailed sectoral reports and, for example, the BCC report is only discussed by the Commission on Culture, Education, Research, Youth, and Mass Media before being presented to parliament. This limits the capacity to focus on the issues in the report and does not provide sufficient access to relevant information to foster media resilience. At the same time, parliament could establish an inquiry committee to investigate hostile media activities on the country’s territory, but this does not seem to be the course of actions chosen by the political leadership.

On July 17, 2017, a working group focused on the improvement of mass media legislation was created to deal with a range of issues, including information security. According to the published agenda, the group aims to draft a ‘National Information Security Strategy’ as well as update legislation on mass media, targeting, amongst other issues, information security. This ambitious agenda, though, must contend with a series of issues. Civil society considers the BCC to be politically dependent, so extending its powers without ensuring its independence may not lead to a better media landscape, rather to undue political control over broadcasters.

Drafting the ‘National Information Security Strategy’ would be an essential step in promoting a better level of media resilience, but it must stem from the NSS, which needs to be updated since 2015 according to its own requirements. The adoption of this umbrella policy document though seems problematic due to the complex political landscape of the country. President Dodon is openly pro-Kremlin and he has made it clear that he will not accept the NSS because it would antagonise the Russian Federation. He has withdrawn the draft NSS proposed by the former president, Nicolae Timofti, claiming that its contents no longer correspond to the substantial changes that have taken place in the national, regional, and international security environment.

The position of the Administration of the President was made clear to us by one of its representatives:

‘The NSS must be geopolitically neutral to be approved by the president. At the same time, the adoption of an Information Security Strategy is a crisis waiting to happen. If it is going to be adopted as law, it must be approved by the president. He will likely reject a bill that will target the rebroadcasting of Russian media outlets. If he proposes a new NSS project that will not comply with the pro-European orientation of the current parliament, it will most likely be rejected as well. This stalemate is going to affect the process of the formulation of effective policies granting a better media resilience level’.

A third option is to adopt the ‘Information Security Strategy’ based on the existing ‘Information Security Concept’. This document only deals with cybersecurity and the integrity of confidential information. While the Ukrainian example shows that protecting critical information infrastructure is an imperative for the state, such decisions would represent a missed opportunity for parliament to promote a more comprehensive information-security policy:

‘One of the issues with the government implementing measures to protect information security is that they are not transparent. Earlier this year, some Russian diplomats and journalists were declared persona non-grata. At the same time, the ISS, as well as the government “failed to convince us” why that was needed or useful … If you declare yourself pro-European, you should act accordingly”.

The incentive policy proposed by parliament to promote national content represents a novel way to foster media resilience against the prominence of Russian content. At the same time, as we have pointed out earlier, the most essential broadcasters on the Moldovan market are closely linked to politicians. Most notable are the four most popular TV channels owned by the leader of the Democrat Party, Vladimir Plahotniuc, and people affiliated to him. The tax incentives might prove to be a way to maximise profits for the broadcasters without affecting the media resilience of the country:

‘The implementation of the ban on rebroadcasting Russian TV might stumble on economic interests. The Russian TV channels are popular and bring profit through advertising to some politicians. Politicians responsible for making decisions are unlikely to take decisions against their own business interests’.

As described above, the institutional cooperation on issues of promoting information security in Moldova is dependent on political aspects and fails to provide genuinely independent agencies to regulate the media market. This affects the prospects of improving the national policy on enhancing media resilience towards hostile activities.

Digital-Debunking Teams

In the Republic of Moldova, there are three major initiatives to expose and combat disinformation, including one that deals with reporting fake social media accounts used for promoting hostile narratives. The number of initiatives is not very impressive but the situation will change in time once Moldova will be able to access the Countering Russian Influence Fund (CRIF), estimated at 250 million USD for the fiscal years 2018-2019. The core issues for the local initiatives are essential funding and resources to monitor and efficiently report on ‘fake news’ and promote different narratives.

One of the first and the most significant initiative is the ‘Stop Fals!’ campaign initiated by the Association of Independent Press (API). Through this project, API aims to build the capacities of independent media and its network of member-constituents through specialised service provision. It also plans to develop a media campaign against fake and tendentious information (in partnership with the Independent Journalism Centre (IJC) and the Association of Independent TV-journalists in the Republic of Moldova (AITVJ). Among the activities to promote these goals, API supports writing and publishing journalistic materials revealing false and tendentious information. It has also produced several videos and audio investigations about propaganda and publishes a monthly newspaper supplement about propaganda.

As a strange sign of the project’s success, we can point to a fake (imitation) site called stopfals.com that appeared, promoting false debunking stories on the web under the real project’s brand. It is important to mention that ‘Stop False’ has chosen not to limit itself to the web and disseminates its findings to local newspapers to reach a broader audience that does not necessarily have the access or skills to use the internet.

Unfortunately, the campaign only deals with local content. This limits the capability of the campaign to fight against all the pro-Kremlin narratives concerning the Republic of Moldova that come from original Russian sources, and sometimes even Western media. This project can be best described as a useful tool to monitor local media and promote ‘fake news’ awareness culture in the country.

The Sic.md project has ambitious goals to identify lies, inaccuracies and manipulations in public impact statements and inform citizens in a simple and accessible way. Sic.md also deals with monitoring the public promises of politicians as well as notifying breaches of ethics in media and public declarations.

The website has a very user-friendly interface. The team strives to have daily posts that represent a synthesis of the day and long reads on complex issues linked to media manipulation. The website also has a report section for a user to email the debunking team. As one of the team members explains,

‘it’s really hard to convince someone in fact-checking messages with opposite views, if not impossible. Our goal is to equip our readers with arguments for personal interactions based on facts that might make a difference’.

Among the limitations of this initiative is that it is limited to one website, compared to ‘Stop Fals!’, which publishes its articles on several websites and newspapers. Additionally, it does not have a developed communications component, most likely because of a lack of resources.

Sic.md also can be considered a tool for political accountability, including for pro-Kremlin politicians’ declarations, which expands its coverage compared to the ‘Stop Fals!’ campaign.

The TROLLESS project was developed during the 2nd Media Hackathon ‘The Fifth Power’, organised by the Centre for Independent Journalism and Deutsche Welle Akademie. The primary purpose of the project, a browser extension, is to identify the sources of manipulation in new social media spaces and to isolate them.

The extension helps track false profiles or those who display suspicious or trolling activity on Facebook and other platforms. Users can report them for promoting interests, parties, ideas, causes, misinformation, manipulation, and distraction. This does not affect the availability of the fake accounts, but the people using the extension can see that those accounts have been reported and can analyse the situation accordingly. The Trolless community has more than 800 users on the Chrome platform, and the authors are considering extending it to other platforms like Mozilla or Safari. This project deals exclusively with social media and is only available to users who have installed the extension in Google Chrome.

The number of digital-debunking teams in Moldova is insufficient because of the limited resources available for this type of activity. All depend on foreign financial support and may not be sustainable for the long term if this support stops. According to the authors of the projects, the state has not shown interest in developing such initiatives and generally ignores the results of their activity.

Media Literacy Projects

Media literacy projects are also quite limited in Moldova. In analysing the last three years, we can emphasise the following three developments.

In 2014-2017, the Centre for Independent Journalism (CJI) organised 71 media education lessons, training nearly 2 000 students and teachers from all over the Republic of Moldova. During the activities, the participants learned how media works, what the role of the press is in society, what rules should be observed when writing a news story, how to distinguish false news, and how to avoid propaganda and manipulation in media. Visits were conducted in schools, high schools, universities, and youth centres.

Novateca is a network of more than 1 000 public libraries in each of Moldova’s 35 administrative regions, providing the public with 21st-century technology tools, digital literacy learning resources, and community services that address local needs. It has reached more than 450 000 visitors by improving their internet skills and accessing public services online.

The ‘Media Education’ course was developed and implemented by the Youth Media Centre in partnership with Deutsche Welle Akademie and the Ministry of Education in November 2015. It has included 63 young people aged 14 to 20 from four educational institutions (three high schools in Chisinau, Drochia, and Cahul, and the ‘Alexe Mateevici’ Pedagogical College in Chisinau). Among the topics addressed within the course were journalism ethics, use of social media and social networks, and manipulation in mass media. This course was also promoted by the TV show ‘Abrasive’, broadcast by public TV station Moldova 1 in 2015.

During the inaugural Mass Media Forum that took place on October 27-28, 2015, in Chisinau, former Minister of Education Corina Fusu declared that the institution was considering introducing several media education classes within the civic education discipline. This was based on the concept of integrating media literacy into school and university curricula as developed by the Independent Journalism Centre. Fusu saw it as a priority to educate young citizens to distinguish sources of information and develop a critical attitude towards mass media. However, this initiative has not come to fruition yet. At present, the Centre for Independent Journalism is piloting some elective media education classes for primary school. The head of the centre believes that the courses should be mandatory and should target high schools more than primary schools.

Conclusions

The Moldovan media resilience profile presents a fragmented and uneven landscape. The governing party has declared repeatedly that it prioritises the fight against propaganda but this has yet to transfer into clear policy measures. Some of the prior decisions in dealing with linguistic issues, as well as the lack of political will to implement the requirements of the ‘Broadcasting Code’ have led to a media market dominated by Russian media. The structure of media ownership suggests that this situation favours a series of political actors who allegedly control some of the most popular TV channels in the country.

At the same time, the implementation of more active measures to counter foreign propaganda may give the regulators means to limit the freedom of the press. Therefore, a prerequisite for implementation of sound policy against media manipulation should be ensuring the independence of the BCC and broad civil-society participation in the process of the selection of its members.

This study has also established a series of other recommendations for enhancing media resilience in the Republic of Moldova in the legal framework, policy measures, and civil society.

Recommendations

Legal framework enhancement:

- Review the ‘Law on the press’ to reflect the realities of the digital age and develop a registration system for news agencies and newspapers. This system should include nudging measures, such as rating media outlets that perform their roles without using manipulation techniques, as well as mechanisms to sanction media outlets that openly promote propaganda. Due to the sensitive nature of this review, it should take place in cooperation with the media community and use the standards of the deontological code promoted by the community. A balanced system would gain legitimacy and trust from the population, as well as discourage local actors who help promote propaganda.

- Close the loopholes in analysing ‘local media products’ and ensure the application of existing norms of the ‘Broadcasting Code’. This measure might be painful to implement in a short period and might require the BCC to give a grace period to broadcasters to adjust to the legal requirements.

- Clarify the role of the ISS in fighting foreign propaganda under close parliamentary scrutiny. The ISS can be instrumental in establishing who the ultimate beneficiaries of local media outlets are and monitoring the activities of foreign agents who give aid to local actors in promoting pro-Kremlin propaganda.

To the government and competent state bodies:

- The National Security Strategy should be revised per legal requirement to reflect the new security environment, which has shifted since 2011. Information security should not be limited to cybersecurity, as it is in the Information Security Concept adopted by parliament.

- A better reporting system should be created for the BCC, the ISS, and the Ministry of Justice to coordinate their efforts in ensuring information security. Parliament, as the primary democratic supervisor, could take a leading role in the operationalisation of the gathered information into policy decisions.

- The initiative to ban broadcasts from countries that have not signed the European Transfrontier Television Convention represents a ‘quick fix’ approach and will not lead to positive long-term effects. Media outlets can choose to register in signatory countries or to adapt media content with the help of national broadcasters. National authorities should promote their narratives to counter propaganda by using both official and unofficial channels, including the national public broadcaster.

- The Ministry of Education should restart the initiative to include media literacy in the school and university curricula, drawing on the success of existing projects in civil society.

To civil society:

- The media community should reactivate the Ethics Committee to analyse the results of monitoring of national media. The Press Council should promote signing the deontological code through a visible brand that the signatories of the code could use.

- Debunking initiatives should report current findings through official channels to the BCC. Although the sanctions applied by the agencies rarely represent an impediment to the media outlets that promote propaganda, they contribute to the dissemination of the results of the debunking teams and the news behind the false narratives.

- Media literacy initiatives should expand to include ethnic minorities and the elderly as communities susceptible to media manipulation and who may lack the necessary skills to analyse information critically.