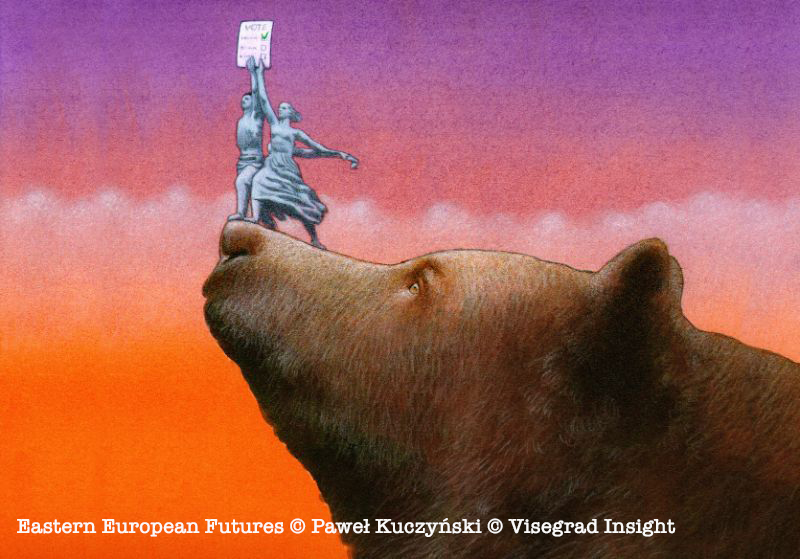

It follows a global rise of popular protest movements with a discernible impact on the political process across the world. People in the streets or ‘people power’ is what drives an agenda of greater prosperity, access to education and expanded economic opportunity. Although this is based on a domestic, bottom-up driver of activism, to some degree independent from foreign actors and external variables, this trajectory is characterised by a stagnant and distracted West and an ineffective or disengaged EU.

Developments in recent years have led to a constructive and realistic reassessment of past failures, a recognition of the need to change the fundamentals of prior approaches and the recognition of the limited inherent capacity to drive change in the region from the outside. This coincides with a declining Russia, which is neither appealing nor a model for the Eastern Partnership countries, thereby only bolstering the reliance on home-grown activism focused on practical domestic needs and aspirations.

Within the parameters of this more localised scenario, there is no real prospect of greater integration nor any significant aspiration for EU membership in the short-term, but rather, a strategy of self-sufficiency to deliver on the practical expectations of citizens.

This means that the EaP countries are somewhat left to their own devices and create a promising and more authentic opportunity for greater intraregional cooperation as well as interconnectivity. Yet such possibilities are hampered by a resistant and recalcitrant leadership in some of the countries, which in response provokes greater civil society mobilisation and bottom-up pressure. Just like the non-violent success of ‘people power’ of the Armenian “Velvet Revolution” example, societies in other countries seek to take control.

In response, the EU offers limited support in these emancipatory efforts. Although there is some symbolic encouragement from the Nordic and Baltic states, the Franco-German tandem plays more of a pivotal role. But the uniform response from EU officials and member states’ leaders is limited to an offer of moral and principled support for the movements, well short of any new funds or tangible forms of assistance. Despite these limits, the local movements do not expect more. The EU’s message is taken as a confirmation for their own local strategy of self-reliance and self-sufficiency as the only way forward.

Following this, new leaders emerge spontaneously from civil society and are endowed with far greater credibility and credentials than the post-Soviet generation who they first marginalise and then replace. These new leaders leverage their local legitimacy into an avenue for taking on the burdens of tackling corruption and strengthening the rule of law, and forging a foundation for sustainable reform.

A central achievement of the resulting political program is the ability to expand into economic reform, pushing an agenda of transparent privatisation, closing down and consolidating inefficient state-owned enterprises, and relying on market competition to weaken and eradicate oligarchic structures in the economy. As an outcome, the reforms bring closer integration among the six states, with a preparatory discussion about a regional free trade area. Despite a weakened Russia, there are no major strategic realignments because of a tacit agreement with Kremlin: direct interference and hybrid warfare are excluded if the countries’ vow to maintain the pre-existing parameters of foreign policy. While this pragmatic agreement offers some superficial stability, there is no lasting resolution of the frozen conflicts in the region nor any other major foreign policy breakthrough.

There are some improvements in the educational sector, recognised as vital for the institutionalisation of sustainable reform. These gains include greater private-public partnerships, more institutional competition in higher education and an increase in teacher salaries. Additionally, the countries pursue trade diversification, with a search for new partners, such as China with its alluring One Belt One Road Initiative, and emerging markets in Asia and Latin America.

Overall, however, the immediate and short-term benefits from major reform remain less than desired and the new leaders are challenged by dangerously high expectations.

As this threatens to trigger a loss of trust and popularity, the imperative is for an unprecedented degree of leadership and statesmanship, which can only be attained through accountability and the capacity to graduate from states dominated by individual democrats to systems defined by institutional democracy.

In ten years, carried by a global wave of protest movements, the Eastern Partnership countries are assertive in their pursuit of democratic standards and build up systemic resilience as a pillar of their sovereign resistance to foreign influence.

Country-specific scenarios

Armenia

The significance of Armenia has never been as highly recognised as its “Velvet Revolution” becomes the model for a ‘brave new world’. Across the region, civic activism is embraced as the most effective pathway to power and youth activism emerges as the agent of change. Within this new context, given Armenia’s small size, both in population and territory, the country is too small to fail, articulating and embodying an inspiring message that it doesn’t take many and it doesn’t take much for real change. Although there is a stark recognition of the inherent limits and failed policies of the EU and the West, an equally candid assessment finds fault and failure with the Russian model. Thus, politics becomes much more local, based on home-grown activism, but also more regional and global, with a new shared commitment to broader common issues.

Azerbaijan

Growing frustration over the failed reform process, deepening economic crisis and poor social conditions have led hundreds of thousands of people to the streets in Azerbaijan. Prolonged street revolts lead to violence and eventually oust the president who flees the country for Moscow. The power gap opens the door to a new violent confrontation between religious groups and the traditional secular opposition. Strong engagement of Azerbaijan’s civil society and support from the West that steps in out of fear for spillover effects for the entire region eventually helps tilt the victory towards the secular pro-democratic camps.

Belarus

Street activity and civil society play less of an important role in Belarus compared to other countries of the region, although Belarusian authorities are forced to pay notably a lot more attention to social requests. The government keeps severe restrictions on dissident public assemblies and political self-organisation of citizens. The leading role in changing the socioeconomic landscape and the rules of the game for businesses depends on young technocrats. This group of young reformers is gradually formed in the next decade as an upper-middle political class. However, they remain partially trapped under the existing political experience in their vision of reforms.

Georgia

Encouraged by the positive role the EU delegation played in dealing with the recent political crisis in Georgia, civil society actors search to emulate this role and focus on the strategic needs of the country. The protracted absence of robust democratic checks and balances, a lack of systemic reforms of the judiciary and government accountability endanger Georgia’s future as a functioning democracy. Civil society goes on the street to address these issues but also pressures the political class to change its state-centric approach and allow for the involvement of non-governmental actors. While the EU takes more distance after years of close relations, this empowers civil society organisations to fill the void.

Moldova

The internal divisions and limited capacities of Moldova, with no prospect of greater integration, may stall the reform process. Weak governance, corruption, oligarchy, weak economy and dependence on remittance from expatriate workers contribute to the outflow of the population. As a result, activism and reformist sentiments of civil society grow. The role of the youth in political processes is increasing. There is an understanding that the ability to change the political situation in the country directly depends on the level of political literacy of the population. More attention is focused on education, activism and strengthening the position of the younger generation. Democracy is gradually being strengthened in Moldova. Meanwhile, the country maintains an apparent neutral position in terms of foreign policy.

Ukraine

A new generation of civil society actors emerges in Ukraine. They enter politics and become a dominant voice for the future of the country, while conventional pro-EU and pro-Russian parties face decline. As a result, Ukraine strengthens its ambition to be a model and leader for the region. Georgia and Moldova are seen as key partners but the doors remain open for the other countries. Ukraine also attempts closer ties with Central Europe through existing regional platforms such as the Visegrad Group and the Three Seas Initiative. There is also deepening cooperation with emerging global players such as India and China, to compensate for limited domestic resources and a lack of support from the West.

Download the PDF

Editor-in-chief

President Res Publica

Wojciech Przybylski

Co-editor of the report

Joerg Forbrig

© Visegrad Insight © German Marshall Fund of the U.S.”

This publication is a result of a joint effort of Visegrad Insight and the German Marshall Fund of the United States to chart possible trajectories for the Eastern Partnership region. Project partners include the Slovak Foreign Policy Association, the Czech Association for International Affairs, the Hungarian Centre for Euro-Atlantic Integration and Democracy, the Foreign Policy Council “Ukrainian Prism”, the Belarusian House and the International Strategic Action Network for Security.

This report has been supported by the International Visegrad Fund. It does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Visegrad Group or the International Visegrad Fund. An earlier thematic report named Eastern Partnership 2030 Trends was developed with the support of the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs.