Introduction

Estonia has been in the orbit of Russia’s strategic interests for many years and for many complex historical reasons. As a result, Estonia has experienced various types of influence activities on different scales. Since regaining independence in 1991, Russia’s so-called ‘soft power’ in Estonia is both traceable and observable in several domains, such as the economy, public diplomacy, political life, and culture. To pursue Russia’s geopolitical goals, it has been using various tools towards Estonia: media influence, cyberattack, compatriot policy, energy dependence, espionage activities, etc. In 1998, a comprehensive overview of Russia’s attempts to influence economic, societal, and political processes in Estonia was published in the annual reviews of the Estonian Internal Security Service.

A classic example is the Kremlin’s support and funding of people (e.g., representatives of the Legal Information Centre for Human Rights and the Russian School in Estonia) who actively promote anti-Estonian propaganda narratives at international events abroad. Moreover, counter-intelligence provides evidence about ongoing violent activities against Estonia and the preparation of computer-related crime. There is also an acknowledgment of threats posed by activities of pro-Russian GONGOs which focus on the negative impacts on Estonia’s internal security.Additionally, monitoring of similar attempts has been included in the Estonian Foreign Intelligence Service’s annual reports on security environment assessments beginning in 2016, and the Estonian Information System Authority annual assessments highlighting cybersecurity events.

The International Centre for Defence and Security, one of the leading think tanks in the Nordic-Baltic area, has also produced numerous studies and analyses dedicated to the assessment of Russian strategic interests in Estonia. Among such interests, experts highlight the creation of tensions, sowing confusion and mistrust within the society, rewriting recent history, and amplifying discrediting lies about Estonia on the international stage. Russia retains a diverse toolbox of influence activities whose intentions are far from friendly. As one of the interviewed experts pointed out,

‘During the last two decades, Russia’s activities towards Estonia have been either chilly, neutral, or openly hostile, quite often with a hidden agenda to undermine the essence of Estonian statehood, to rewrite our history, to corrupt our politics, and make it in the end more similar to and dependable on Russia’.

There is a general consensus that Russia’s increased military activity and aggressive behaviour is mirroring its hostile influence activities. This can pose immediate threats to Estonia’s security, as it primarily depends on the Euro-Atlantic region’s security situation, relations between its neighbouring countries, and public resilience.

Vulnerable Groups

It is widely recognised that the Russian regime is extremely opportunistic. Therefore, it exploits the weakest points and the most vulnerable groups of the targeted societies and countries when planning and executing influence activities. This broadly sets the context in which Russia operates. It should be noted that 17 of the 24 surveyed experts agreed that Russian media tend to exploit Estonia’s economic, historic, societal, and ethnolinguistic contexts in an attempt to spread its hostile narratives.

In Estonia, one of the most obvious groups to be targeted and influenced by Russia is the Russian-speaking population, which makes up about 28% of the general population of Estonia. Besides other groups, the interviewed experts considered this group particularly vulnerable to Kremlin-backed influence activities. Nevertheless, some ethnic Estonians might be clustered around other small and rather uninfluential groups, which can be considered as a possible target for Russia’s activities, with a reference to some business people whose commercial interests are strongly linked with Russia. This may also include a small percentage of pacification-minded people who think NATO is just provoking or even irritating Russia. Some other pro-Kremlin narratives might seem to be somewhat appealing to those ethnic Estonians who are strongly nostalgic for their Soviet past, are socio-economically disadvantaged, and/or support xenophobic rhetoric.

Still, as pointed out by one interviewed expert, ethnicity provides a cognitive shield of protection:

‘There is a strong sense that, because of a brutal history and fresh memories of the Soviet occupation, because strong anti-Russian narratives remain in many families, almost all ethnic Estonians have a kind of immunity against the totalitarian lies and disinformation campaigns delivered nowadays by the Kremlin. Unfortunately, it is not the case for many local Russians, whose historical background is different. They should start learning and accepting the truth, not a Kremlin version of it’.

For a dozen years, Russian-speakers have been portrayed as quite monolithic and a rather inactive part of Estonia’s society. Although, clustered exclusively according to language, this group is indeed very heterogeneous and multidimensional in terms of its ethno-cultural background, citizenship, political activity and preferences, educational and socio-economic parameters, proficiency in the Estonian language, media consumption, etc. The Russian-speaking population of Estonia is one of the most researched groups within the society mainly because of the state-supported and state-directed integration process. Some recent studies give an exhaustive overview on its various descriptive parameters as well as highlight major challenges to the integration process. According to one of the interviewed experts,

‘Approximately 15% of Russian-speakers have very weak state identity, they do not affiliate themselves with the Estonian state or society, they do not honour our national symbols, and they prefer to live mentally in the Russian space’.

According to the results of the integration study, five main patterns of Russian-speaker integration emerge: (A) successfully integrated (21%), (B) Russian-speaking patriots of Estonia (16%), (C) critically minded people (13%), (D) little integrated (29%), and (E) unintegrated passive (22%). Another recent study suggests distinguishing four main clusters of Estonia’s Russian-speakers in the following terms: assimilation (23%), separation (34%), integration (22%) and ignorance (19%). Evidently, one of Russia’s goals is to obstruct or diminish societal cohesion, because there are such divisions in Estonia.

Until the provocative events of April 2007, relations between ethnic Estonians and local Russian-speakers had been remarkably peaceful. The next peak of noticeable polarisation between the two groups began in 2013 and was caused by the developments in Ukraine. The crisis, followed by the war, revealed the sizeable influence of ethnic heterogeneity, and the power of minorities to cause severe political unrest when feeling oppressed and underprivileged. Until then, many Estonian politicians and policymakers did not fully realize that formal indicators of integration, such as language proficiency or citizenship, are indeed poor indicators of a meaningful sense of belonging among local Russian-speakers or their perceptions of the state and national security.

At the same time, the issues of native language in regards to citizenship or the teaching of the native language at school have been irresponsibly over politicised in almost every election since regaining independence. The recent municipal elections on October 24, 2017, once more demonstrated the trend of the Russian card being widely played by several Estonian political parties. The crisis in Ukraine added another dangerous dimension to an already complicated situation. Beginning in 2014, the position and perceptions of local Russian-speakers in Estonia have been publicly discussed and presented through the prism of security both on a national and international scale.

The question, “Will Narva be next?” suddenly became displeasingly popular. The securitisation of one particular group within the society might raise some unjust concerns about its loyalty and consequently lead to a deepening distrust among other members of society. One of the interviewed experts rightfully noted that Russia makes both visible and hidden efforts to consolidate the Russian-speaking population outside of the mainstream Estonian society. The effects raise the social and political salience of cultural issues, leading to linguistic and ideological confrontation.Among the most active means for that is pushing Russia’s compatriot policy as well as ensuring Russian media domination and its attractiveness. To quote an expert,

‘Russian television invites Estonia’s Russian-speakers to join a virtual ‘Russian World’, the same mental universe in which many Russian citizens live, a world united by language, culture, religion, history, and blood’.

Media Landscape

In general, three main media segments can be distinguished in Estonia: national Estonian-language media, local Russian-language media and foreign media (including Russian-language media in Russia). Several indicators lead to the conclusion that in Estonia the media enjoy a high degree of freedom. According to the World Press Freedom Index, Estonia ranks 12th as of 2017. This is the highest ranking among the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Estonia shares first place with Iceland on the global list “Freedom on the Net 2017”. There have been no documented cases of violent government interference into media policy, and freedom of the press is generally perceived as an absolute right. Naturally, freedom of expression and freedom of speech are protected by Estonia’s constitution and by the country’s obligations as a member state of the European Union.

While there is a general awareness of Russian information campaigns designed to manipulate public opinion, there have not been any incidents of banning content from Russia. On the other hand, since the Russian-language media are considered by several information-security experts to be a tool for spreading disinformation and hostile propaganda in and against Estonia, it is necessary to take a deeper look at the patterns of media consumption.

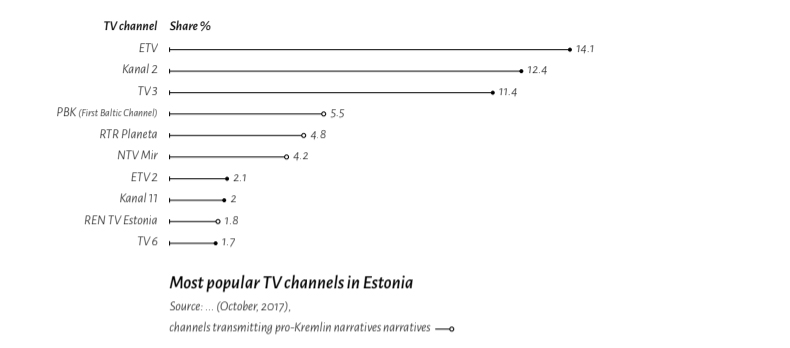

In October 2017, data from Estonian media monitoring demonstrated that the most popular TV channels (daily share) among Russian-speakers were: PBK (First Baltic Channel) (15.9%), RTR Planeta (14.1%), and NTV Mir (11.4%). The listed TV channels can be reached through normal cable television. Naturally, Russian-speakers also prefer Russian-language radio stations (as of summer 2017): Radio 4 (13.5%), Russkoje Radio (12.6%), and Narodnoje Radio (11.5%). In 2014, more than 70% of local Russian-speakers claimed that an important source of news information was Russian-language TV channels.

The web-portal rus.delfi.ee is the most visited by Estonia’s Russian-speakers. Other popular websites in Russian include: seti.ee, vecherka.ee, ria.ru, kinozal.tv, mke.ee, and kinopoisk.ru. Interestingly, social media networks are a more important source of information for young Russian speakers than for young Estonian speakers. Another study indicates that local Russian-speakers write comments to online articles more than ethnic Estonians. Overall, there are still some big differences in the patterns of media consumption between ethnic Estonians and Russian-speakers in Estonia. For instance, the main conclusion of one recent study is that Russian-language social media networks are being actively used for generating and distributing hostile narratives and toxic disinformation.

One of the interviewed experts suggested that the consumption of Russian-language media might prove that the vast majority of local Russian-speakers live in Russia’s mental space, and therefore, could be influenced by hostile narratives:

‘They are extremely accustomed to obtaining news from, enjoying entertainment, and watching movies on the Russian channels, or spending their time on social media networks like VK or OK, where the content is usually charged with uniquely toxic views and has extremely huge lies or weird versions of the truth. Very often, the picture does not correspond to reality at all’.

Fourteen of the 24 surveyed experts shared the opinion that Russian media is generally trusted among local Russian-speakers in Estonia. Similar assumptions have been made in other studies of media. The result of this is that multiple recommendations also have been made focusing on how Estonian society can defend itself from Russia’s orchestrated disinformation. Some scholars argue that the deregulation of media undervalues the potential of Russian disinformation and fails to fully equip Russian-speakers with the necessary protection against hostile propaganda.

Legal Regulation

In general, the Ministry of Culture is responsible for Estonia’s broadcasting policy. The role of independent media service controller is given to the Estonian Technical Surveillance Authority under the administration of the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communications.

The applicable EU legislation includes the AudioVisual Media Services Directive. There is also a set of specific regulations in Estonia, which along with the code of ethics, affects local media. The broadcasting sector is regulated directly by the ‘Media Services Act’ and ‘Estonian Public Broadcasting Act’. These set quite strict regulations on broadcasters and guarantee freedom of operation, protection of information sources, and the right to reply, etc. Media self-regulation consists of the Estonian Press Council. In 1998, a Code of Ethics for the Estonian press was adopted, and it is used as the main instrument for media accountability.

According to interviewed experts, the current legal foundation provides a solid base for media activities in Estonia; however, there might be some unregulated issues to be potentially exploited by disinformation campaigns:

‘As fake news spreads very quickly and can bring along reputational damage, not just for persons but also institutions and organisations, we might see in the future some regulatory gaps and consequent delays in responding to that’.

Moreover, there are other laws that indirectly regulate the media landscape. Namely, the Estonian Penal Code provides protection from activities that publicly incite hatred, violence, or discrimination based on nationality, race, sex, language, origin, religion, sexual orientation, political opinion, or financial or social status, if the activity results in danger to the life, health, or property of a person. Defamation was decriminalised in 2002 and civil defamation cases are regulated by the ‘Law of Obligations Act’. The ‘Personal Data Protection Act’ restricts the collection and public dissemination of an individual’s personal data. No personal information that is considered sensitive—such as political opinions, ethnic or racial origin, religious or philosophical beliefs, health, sexual behaviour, or criminal convictions—can be processed without the consent of the individual.

Institutional Setup

Today, there is broad political consensus on and wide societal acknowledgement of the threats imposed by Russia’s hostile activities against Estonia. Many Estonian experts agree on the need to have an adequate and clear understanding of the challenges and current vulnerabilities. A course of action has been stipulated in the Estonian security policy, ‘National Security Concept 2017’, based on shared views and results of analytical studies.

This document addresses the current security environment while framing national diplomacy, military defence, protection of constitutional order and law enforcement, conflict prevention, and crisis management. It also specifically addresses the issues of economic security and the supporting infrastructure, cybersecurity, protection of people, resilience, and cohesion of society. Explicitly, it provides definitions of strategic communication and psychological defence as well as highlighting the importance of generating reliable information and general awareness aimed at strengthening national resilience.

As previously noted, the situation is being continuously monitored by the security services. The same services are informed by the public about the most sophisticated and imminent threats to information and psychological security. According to several of the interviewed experts, the societal resonance to this threat helps to calibrate some countermeasures:

‘We trust our citizens and their feedback provides us assurances for open communication, which is crucial for strengthening national resilience’.

Respective activities are coordinated across the Estonian government’s ministries and agencies through the National Security and Defence Coordination Unit. This unit advises the prime minister on national security and defence matters, and coordinates the management of national security and defence. While communicating to the public, each state institution coordinates its actions with the main principles listed in the Government Communication Handbook. Almost all interviewed experts expressed the confidence that they observe a high level of institutional development in the sphere of information security in Estonia. The same applies to the level of comprehensiveness of the legal frameworks in terms of detection, prevention, and disruption of informational threats and vulnerabilities.

In Focus

In 2011, the National Centre for Defence and Security Awareness (NCDSA) established an Estonian non-governmental expert platform for strengthening national resilience by means of applied research, strategic communication, and social interactions. NCDSA’s long-term vision is a secure society that is psychologically resilient, socially cohesive, and resistant to hostile influence. The NCDSA runs a state-supported training programme called Sinu Riigi Kaitse. The programme’s aim is to inform Russian-speaking communities of Estonian national defence and security issues by initiating and organising public events. It also strives to induce discussions that promote awareness of the Estonian, NATO, and EU security and defence policies among Russian-speakers in Estonia. Additionally, the NCDSA monitors and analyses security- and defence-related perceptions of Russian-speakers in Estonia. NCDSA’s most recent study is an analysis of Russian-language public posts and profiles on social media in Estonia. Among other activities, the NCDSA produces Russian-language materials aimed at inspiring and empowering young Russian-speakers by highlighting personal success stories in Estonia’s security and defence sector.

Among other state institutions and in addition to military means, the Estonian Ministry of Defence plays a vital role by supporting and strengthening the bond between citizens and the state. The ministry has a long-standing tradition of conducting public opinion surveys on national defence, the results of which are also analysed through the prism of the native language. These results reveal not only the dynamics of public opinion over the last 17 years but also worrying differences between societal groups.

According to the interviewed experts, the major gaps in security perceptions of ethnic Estonians and local Russian-speakers are mainly related to NATO’s enhanced forward presence in Estonia as well as relations with Russia. For instance, 67% of local Russian-speakers and just 23% of ethnic Estonians support stronger security cooperation between Estonia and Russia. At the same time, 73% of ethnic Estonians and 23% of local Russian-speakers agree that NATO is the best bet for Estonia’s security. Proponents of Estonia’s membership in NATO amount to 31% of local Russian-speakers and 91% of ethnic Estonians—a threefold difference. Predictably, 89% of ethnic Estonians and just 27% of local Russian-speakers approve of NATO’s military presence in Estonia.

There are also big differences in the views of the two groups regarding the war in Ukraine, with 68% of local Russian-speakers and just 2% of ethnic Estonians reporting they think Ukraine bears the most responsibility for the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Meanwhile, 6% of local Russian-speakers and 78% of ethnic Estonians viewed Russia as being responsible for the conflict.

There is arguably no coincidence that these are also the topics around which a higher degree of Russian disinformation can be observed. As discussed previously, it could be suggested that Estonia’s national security-related opinions are largely shaped by pro-Kremlin media channels,taking into account the trust-based receptiveness of many local Russian-speakers in Estonia towards Russian propaganda.

Digital Debunking Teams and Media Literacy Projects

All interviewed experts share the view that the independence and secured freedom of Estonia is strengthened by involving active citizens in the national security conversation. Several initiatives have been adopted and refined across all levels of government and civil society. Non-profit organisations and citizens’ voluntary initiatives have an important role to play in reinforcing national resilience. As an interviewed official of the voluntary national defence organisation Estonian Defence League stated:

‘Being very creative and flexible, motivated volunteers can achieve some tangible results in supporting the state activities in the field of defence and security. Our contribution plays a vital role in diversifying activities that minimise the harmful effects of pro-Kremlin propaganda’

The wider dissemination of knowledge and skills related to national security is regularly supported from the state budget. For example, it is coordinated and organised through the National Defence Course at schools nationwide. Although such training courses are primarily focused on security and defence, there are at least several lessons within the curriculum dedicated to hybrid threats, hostile activities, and the use of information as a weapon. This was (emotive not academic) spotted by an interviewed national defence teacher:

‘My students ask me all the time about some fake news and even about manipulation in social media. Of course, I teach them the basics of media literacy and also present some good examples of debunked myths. It works better when you as a teacher explain it thoroughly, not just suggest boring reading from the internet’.

Additionally, Senior Courses in National Defence are held twice per year in both the Estonian and Russian languages for adult audiences of politicians, senior state officials, military officers, local government officials, top economic and opinion leaders, cultural and educational practitioners, journalists and NGO representatives.

In Focus

An international cooperation platform, Resilience League, was established to train young professionals and experts in practical skills and tools for promoting the transatlantic security and defence agenda as well as strengthening national resilience against hybrid threats. This programme is supported by the Estonian Ministry of Defence, NATO Public Diplomacy Division and Friedrich Ebert Foundation. It unites experts into a professional network with the goal of developing and implementing innovative methods against hostile ideologies and harmful influence. Additionally, it regularly organises various training events and conducts studies. The format of the international schools includes lectures and interactive seminars based on educational discussions and interactions. This format is led by experienced specialists and recognised practitioners from NATO, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Denmark, Georgia, Finland, Ukraine, and other countries.

Remarkable support is provided to several non-profit organisations that deal with the development of national defence and informational security. For instance, the trilingual (Estonian, Russian, English) blog of Propastop is aimed at contributing to Estonia’s information space security. The blog is run by a group of volunteers, many belonging to the Estonian Defence League. Propastop brings to the public deliberately disseminated lies, biased or dis-information in media and other cases of manipulating information. Propastop compares lies with real facts, shows the motives behind the actions and identifies the people interested in manipulating information. Propastop mediates information related to blog topics from state agencies, current media, and literature. Propastop restricts itself only to exposing propaganda, but does have the ambition to become a web site that contains a compendium on propaganda. The flagship and oldest daily newspaper of the Estonian press, Postimees, regularly re-publishes interesting stories from Propastop.

Being part of the Estonian Public Broadcasting, one of the most listened to radio channels among local Russian-speakers, recently started a new rubric dedicated to increasing general media literacy and discussing with experts various topics related to disinformation campaigns and fake news. The rubric is supported by the Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Estonian Ministry of Defence. The CEPA StratCom programme, joined by an Estonian media expert, produces regular briefs and reports on the situation in Estonia. These are often cited in the local press because they are translated into Russian and Estonian.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Almost all experts contributing to this research share the common opinion that Estonian society is remarkably resilient because of vivid historic memories and close interactions between the government and civil society. Nevertheless, special attention should be paid to vulnerable societal groups, such as local Russian-speakers, whose informational and psychological resilience might be attacked by disinformation campaigns through hostile narratives or active measures coordinated by Russia or its proxies. Among the realistically applicable recommendations suggested by the experts in this report, the following three deserve particular attention:

- The Estonian government should continue to involve active members of civil society in practical activities that strengthen national resilience. Different formats of involvement should be supported to capitalise on the synergetic contributions from respective NGOs and volunteers. This should not only be reinforced in national defence but also in areas of internal security, cybersecurity, information security, and psychological security. These activities should be perceived as a long-term investment into national security and their effectiveness should be measured in 7-10 years retrospectively.

- The promotion of national security-related values and virtues within the society should be regularly stated by political leaders and active citizens throughout different levels and on various platforms. These formats should include peer-to-peer, formal education, informal training, embedded in local events and everyday life, community-based approach, tangible presence in social media, recognition of active volunteers in different areas, etc. Such activities should encourage all members of civil society to contribute toward strengthening national resilience.

- A diverse ecosystem of and continuing symbiosis between state institutions, the private sector, and civil society should be promoted and financially supported as a key element to national resilience. Its reinforcement should be based on eliminating obvious internal and external vulnerabilities, providing qualitative and quantitative situational awareness to the decision-makers, adequately informing the general public about current threat assessments, and preparations for and success stories from minimizing the harmful impact of influence activities against Estonia. The characteristic keywords of the ecosystems must be flexibility, networking, complementary, consciousness, and professional dedication.