Introduction

Since the restoration of independence and statehood, Latvia has achieved remarkable results in democracy-building and overcoming its Soviet legacy. However, problems rooted in the Soviet era persist, making Latvia vulnerable and providing a path for the dissemination of Kremlin-led disinformation and propaganda.

Latvia, along with the other Baltic states, can be regarded as a success story in the transition to a liberal democracy, yet the consequences of Soviet occupation continue to be observed in almost all areas related to the national economy and the development of society. Since the restoration of independence in 1991, Latvia has been aiming to strengthen freedom of media and expression. Article 100 of the Satversme (Constitution) defines the foundations of Latvia’s media policy:

‘Everyone has the right to freedom of expression, which includes the right to freely acquire, retain, and distribute information, and express his or her views. Censorship is prohibited’.

According to the estimate by Freedom House in its ‘Nations in Transit’, Latvia consistently is third best among the 29 countries tracked in their consolidation of democracy. This puts the country ahead of others, including Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary, and only lagging behind Slovenia and Estonia.

Accession to the EU and NATO in 2004 contributed to Latvia’s consolidation of democracy and diminished Russian economic and political influence in the country. However, one of the remaining problems is the ethnically divided political environment, which diverts attention from other important issues and increases Russia’s influence in Latvia. There are other issues within the context of Russia’s informational influence to be addressed too, including the divided media space, segregated education system, and unequal regional development. For instance, Latvia’s eastern region of Latgale has more economic and social problems than other parts of the country.

Vulnerable Groups

Russia’s information campaigns in Latvia target and spread individualised content to specific groups in society. Among the major ethnic groups in Latvia, 61.8% are Latvian, 25.6% Russian, 3.3% Belarusian, and 2.3% Ukrainian. The highest proportion of Latvians is in the Kurzeme and Vidzeme regions and lowest in Riga and Latgale. It should be noted that the Russian compatriots’ policymakers try to cluster all Russian-speaking people into one. Thus, the executives of Russia’s information influence policy aim at a large part of the population of Latvia. This includes not only ethnic Russians, but Ukrainians, Belarusians, and others.

Russians living in Latvia are not a homogeneous group in terms of political opinions and values. Since the annexation of Crimea in 2014, several public surveys about general attitudes towards foreign and domestic policies in Latvia indicate significant differences between ethnic Russians in Latvia. Based on the data of these surveys, this part of the population can be roughly divided into three large groups: European-minded Russian-language speakers loyal to the Latvian state and the idea of its existence, ‘neutral’ Russians who are not sufficiently integrated into Latvian society but at the same time are not pro-Kremlin, and those who consider themselves Russian compatriots and support the ideas to construct a ‘Russian World’.

The Kremlin-led propaganda efforts are predominantly aimed at ‘neutral’ Russians (including Ukrainians and Belarusians), whose dissent over domestic policy and the economic situation in Latvia is used by Russia’s public diplomacy agents. However, it must be emphasised that this division is conditional. People may agree on one issue but differ on others, thus not falling into any of the three groups. The main point to remember is that Russia deliberately exaggerates the personification that the entire Russian-speaking population of Latvia always supports Russian foreign policy.

Media Landscape

According to the international organisation Reporters Without Borders’ ‘2017 World Press Freedom Index’, Latvia is ranked as the 28th most liberal among the 180 nations surveyed. This indicator can be considered a good achievement, but there are several problems on closer inspection. One that has been mentioned by several Latvian media and information-security experts is the disproportionately large presence of Russian media in Latvia. Māris Cepurītis, a researcher at the Centre for East European Policy Studies, and Rita Ruduša, director of the Baltic Media Centre of Excellence, mentioned in their interviews that the disproportionally large presence of Russian and Russian-language media that attempts to ensure Russia’s political influence in Latvia is one of the country’s major challenges to its information security.

This is especially noticeable in the package offers by cable TV providers. Russian radio stations are also represented in large numbers on FM radio. ‘Asymmetry’ is a keyword when talking about the entrenchment of Russian information channels in Latvia. Latvian public media in Russian – Latvian Radio 4, the United Latvian Public Media internet portal lsm.lv, and the LTV 7 channel, which broadcasts segments in the Russian language – cannot play the counterweight role to the well-funded and attractive Russian TV channels, such as RTR Planeta, NTV Mir, First Channel, REN TV Baltija, and others present in the information space. One of the major problems is the enormous difference between the funding of the Latvian and Russian TV channels. This contest is largely won by the Moscow channels (at least in primarily Russian-speaking markets).

Russian TV and radio channels are quasi media because the providers can only be partially monitored for compliance with Latvian legislation. Russian TV channels are provided by the authorised representatives of the Russian TV companies, who consist of Russian and Latvian entrepreneurs cooperating with the Russian channels. They receive permission from various channels to retransmit and attract sponsorship from Latvian advertisers. Within this context, the most significant in the Baltic states are the SIA Baltic Media Alliance and SIA Baltic Media Union.

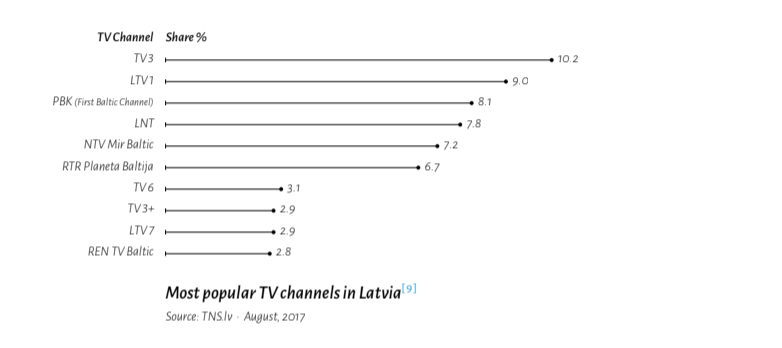

Chart No. 1 shows that the most popular TV channel in Latvia in August of 2017 was TV3 (a commercial TV channel belonging to the MTG group) with 10.2% of the market. The second most-visible channel was LTV1 (Latvian public media), with 9% of the total viewership. The third most-viewed channel was PBK, which accounted for 8.1% of the market. An important note, PBK is broadcast in Russian and about 70% of its footage is made in Russia (retransmission of First Russian Channel ORT) and presents a position favourable to the Kremlin. However, the local Latvian PBK news programs are politically more neutral than the channel’s news broadcasts created in Moscow studios.

LTV7 channel is the Latvian national broadcaster and parts of its programmes are in the Russian language. However, its 8th-9th place in the ratings indicates it is incapable of competing with the Russian channels NTV Mir Baltic and RTR Planeta Baltija, which are ranked fifth and sixth, respectively, among the most popular channels. Another important note, TV channels NTV Mir Baltic and RTR Planeta Baltija are the most active distributors of official Kremlin-backed propaganda in Latvia. PBK and REN TV Baltic have more entertaining programmes. Nevertheless, the content of their news and political discussion demonstrates they are not far behind the other two channels. Consequently, we can conclude that among the 10 most popular TV channels in Latvia, four spread Russian propaganda and disinformation. It can also be established that Russians and Russian speakers living in Latvia (Ukrainians, Belarusians, etc.) prefer PBK.

Commercial channels TV 3, LNT, TV 6, and TV3+ are ranked among the 10 most popular channels and are part of the MTG group. These channels enrich the Latvian media environment through their news broadcasts and entertainment programmes. However, the control of these channels by a single owner decreases competition on the media market.

This situation distorts the domestic policy process because, in part, constituents live within the disinformation and propaganda space of Russia. This leads to influence on Latvian citizens’ formation of their political views and preferences when supporting particular political parties. A 2014 poll showed that PBK Latvia’s news is very popular among the Russian-speaking population in Latvia. More importantly, this audience trusts it. The data showed that this news is mostly viewed by non-Latvians living in Latvia, and in comparison with other news channels available on Latvian TV channels, the majority of its viewers are non-citizens. In contrast, a survey carried out in 2016 concluded that the Latvian-speaking audience showed a lot of trust in LTV and Radio Latvia. The trust index of LTV reaches 72% (regular LTV viewers). The trust index for Radio Latvia is 82% (regular Radio Latvia audience).

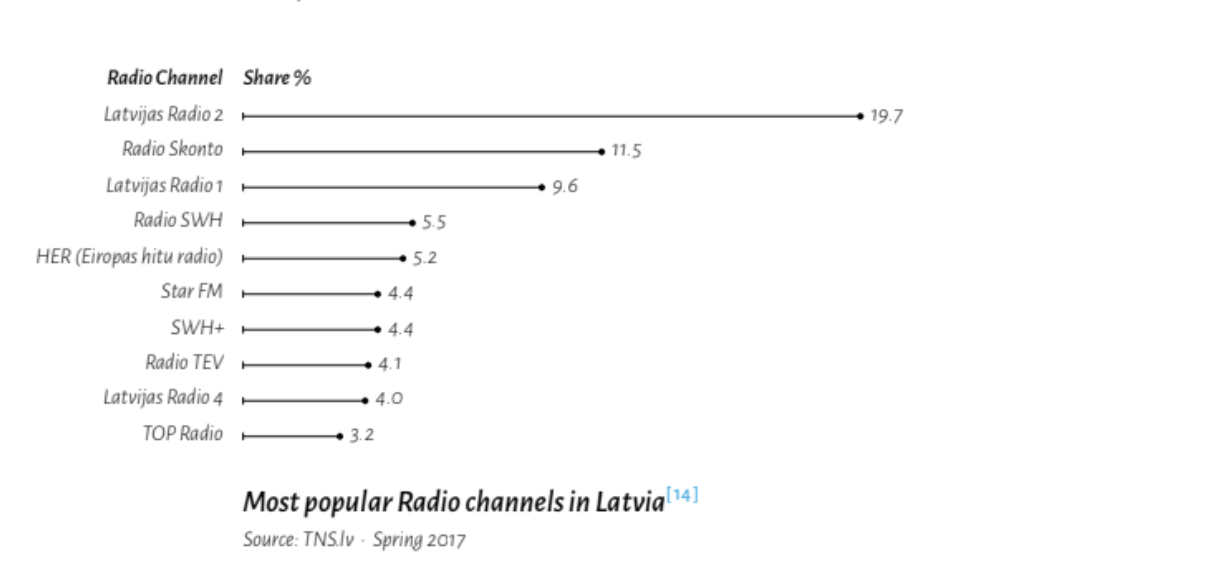

A relatively large number of radio channels operate in Latvia. This includes Latvian commercial and public radio available throughout the country as well as several regional radio stations. Latvian public media, Latvijas Radio 1 (news radio broadcasting in Latvian), and Latvijas Radio 2 (Latvian music radio), were ranked among the three most popular radio channels in spring 2017. This was a remarkable result considering the strong competition.

Three out of the 10 most popular radio channels in Latvia (SWH+, Latvijas Radio 4, and TOP Radio) broadcast in Russian. Latvijas Radio 4 is a public channel that attracts a significant segment of the Russian-speaking audience in Latvia, which is a positive phenomenon in the context of decreasing Russian influence on the airwaves.

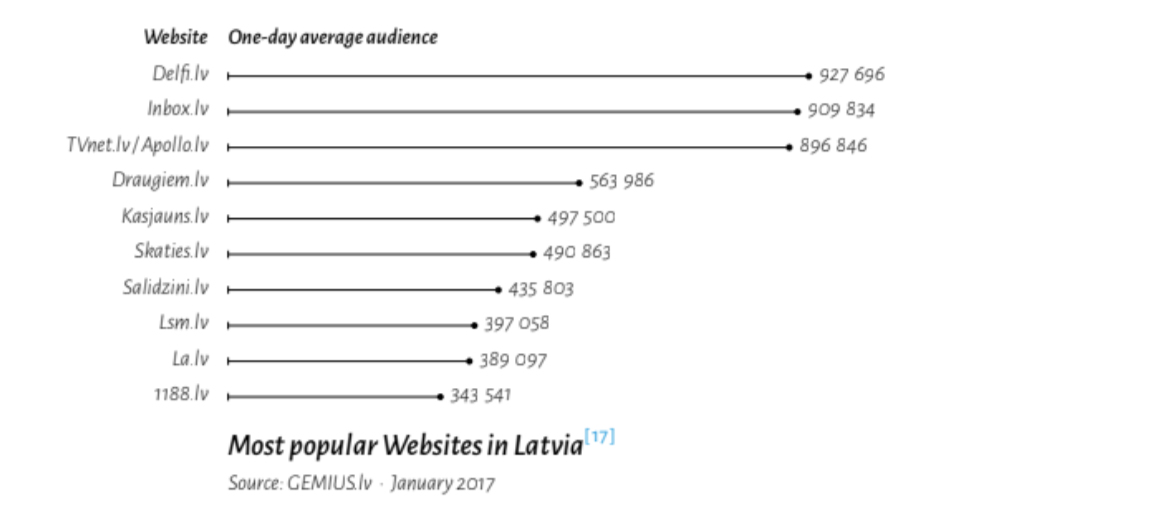

The internet is regularly used by 65% of the population in Latvia. According to 2017 figures, the top three websites based on a one-day average were: Delfi.lv (a news portal in Latvian and Russian), Inbox.lv (in Latvian and Russian), and TVnet.lv/Apollo.lv (news portal in Latvian and Russian).

It is essential to highlight the most popular news portals in Latvia were Delfi and TVnet, which make different content in Latvian and Russian. Such an approach does not necessarily contribute to the consolidation of society, because Latvians and Russians living in the same country encounter different reports and interpretations, even within the same media outlet. Both of these portals have a robust comment sections. Part of the comments are rather aggressive and verge on hatred. However, the web pages’ comment sections are not visited as intensely as 10 years ago. Many active commenters have moved to Twitter, Facebook, and Draugiem.lv (Latvian analogue). In part, Twitter comments have been automated. In its 2017 research, the Riga based NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence drew a significant conclusion that ‘Russian-language bots’ created roughly 84% of all Russian messages about NATO in the Baltic states and Poland on Twitter.

In 2017, a survey conducted by Latvijas fakti (Latvian Facts) showed that Delfi.lv is the county’s most popular news source, followed by two other internet sites (Tvnet.lv and Apollo.lv). Next are the TV channels, Latvian public television LTV 1 programme ‘Panorāma’ as well as the first channel of Latvian Television, and then the commercial channels (LNT, PBK and TV3). The Russian-speaking residents indicated their favourite portal was the Russian version of Delfi followed by PBK’s, and also the LTV 1 news programme Panorāma, among others. About a third of the respondents indicated they used media in Russian. Thus, the overlap between the sources of information used by the Latvian- and Russian-speaking audiences is minimal. The divided information space continues to maintain the split in the political environment among the population and facilitates the dissemination of Kremlin-backed fake news and propaganda in Latvia.

Self-regulation of the media environment in Latvia is aggravated by the existence of two professional journalist associations, the Latvian Association of Journalists (LŽA) and the Latvian Journalists’ Union (LŽS). LŽA was founded in 2010 and has more than 100 members affiliated with newspapers, magazines, radio, TV and internet media. There are also university lecturers among the members. Besides the these two, there are other media-related associations in Latvia, including the Association of Press Publishers of Latvia, the Latvian Association of Broadcasting Organisations and the Latvian Internet Association. Speaking about safeguarding ethical principles of journalism and supporting the professional growth of journalists, the most active and prominent is LŽA, currently headed by Rita Ruduša. She is also the executive director of the Baltic Media Excellence Centre. In general, it has to be concluded that the efforts of professional organisations alone are not enough to counteract the consequences of the massive Russian disinformation in Latvia.

The problem is that LŽS acts rather as a journalists’ trade union, not paying much attention to the ethics of its members. In turn, the Rita Ruduša-lead LŽA maintains a higher standard of professional ethics through its Ethics Commission, but not all Latvian journalists are members. The existence of two organisations rather hampers the process of effective self-regulation within Latvia’s media sphere.

Legal Regulation and Institutional Setup

Media regulation in Latvia mainly concerns the financing, monitoring, and management of broadcasting media (especially public media). According to media expert Anda Rožukalne, the press is poorly regulated and regulatory norms for internet media have not been developed. The regulatory framework of Latvian media is based on outdated normative acts: the ‘Law on the Press and Other Mass Media’, the ‘Advertisement Law’ adopted on December 20, 1990, and the ‘Law on Electronic Media’, adopted on July 12, 2010, which establishes the arrangements and rules for electronic media under the jurisdiction of Latvia. Control of compliance with this law is entrusted to the National Electronic Mass Media Council (NEPLP). The former director of NEPLP, Ainārs Dimants, has indicated in an interview that the Latvian internet media environment is not controlled sufficiently by the state authorities even though it has become an important part of the information space. Dimants also mentioned that it is necessary to raise the NEPLP’s legal capacity to allow it to react effectively to infringements in media activities.

Latvia is subject to Directive 2010/13/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council. This directive coordinates the provision of audiovisual services in EU countries. Unfortunately, the Audiovisual Media Services Directive allows media to be registered in any EU country as long as one of the company’s board members resides in one of these countries. This complicates the regulation of particular organisations within a single country because media is regulated in accordance with the legal acts of the country of registration. This means that channels and media companies working inside Latvia but formally established outside the country may not be subject to the Latvian regulator.

NEPLP adopted the ‘National Strategy for the Development of the Electronic Media Sector for 2012-2017’ following consultations with industry stakeholders. Among the strategic goals are the following: (a) strengthening and reforming public media by increasing their role in bolstering national culture and identity, and (b) providing information space in the Latvian language and the broadcasting of national electronic media throughout the whole territory of Latvia, especially in the eastern border area. In 2017, the NEPLP elaborated the ‘National Strategy for the Development of the Electronic Media Sector for 2018-2022’. One of the most important documents defining state media policy was mentioned in the 2016 ‘Cabinet of Ministers decree No. 667’, which adopted the ‘Latvian Media Policy Guidelines for 2016-2020’.

There is no distinct information-security doctrine in Latvia. Therefore, all of these concept documents both directly and indirectly affect the security of the information space. The ‘National Security Concept of Latvia’ (2011) also focuses on threats to the information space. For example, the concept concluded that,

‘Latvian as a state language and a unifying element of society has not been rooted in several areas, for example, in business and the information environment. Separate information spaces diminish the capabilities of the state to address all of society equally effectively; therefore, a certain part does not form a sense of belonging to Latvia’.

The following task is quoted among the array of solutions,

‘The state must ensure that obstacles are eliminated so that the national information space is accessible to the largest possible part of Latvian society that will take it in everyday use to obtain the necessary information’.

The activities by the NEPLP cover only part of the information-space issues. The ongoing events in the Latvian information space should be regarded in a wider strategic approach. The order by the Cabinet of Ministers of Latvia in the ‘Guidelines for Latvian Media Policy 2016-2020’ designates the Ministry of Culture as the institution responsible for the implementation of the guidelines. In 2015, the ministry established the Division of Media Policy, whose task is to develop media policy but not to monitor media activity in practice. However, according to most of the interviewed experts, Latvia lacks a serious national strategy for information-security policy. This is partly due to a lack of understanding among the political elite about the democratic importance of free media and high-quality journalism. For example, Executive Director of Re:Baltica Sanita Jemberga indicates that,

‘Latvian politicians are hardly declaring in public all the high-quality, free, pluralistic activities of media as a value’.

Jemberga adds that Latvia lacks empirical knowledge on the impact of Russian media on the practical actions of various groups of society.

Digital–debunking teams

There are several projects in Latvia debunking deception by Russian and local media, but given the massive presence of Russian media, one could not say such projects are sufficient. One successful example in news-checking is the ‘Lie detector’ section of the Latvian news portal lsm.lv, which checks whether Latvian politicians and officials are telling the truth. They select statements and examine the facts contained in the interpretative text. However, this is not a project related to Russia’s campaign of deception and lies but contributes to the maintenance of critical thinking of the audience, which becomes accustomed to the idea that facts should be verified.

Latvian media expert Mārtiņš Kaprāns regularly reveals Russian disinformation about Latvia, the Baltic states, and NATO on the website of the Centre for European Policy Analysis (CEPA, www.cepa.org). Kaprāns both illuminates the lies of Russian media and analyses the methods used by Russian propagandists. Once a month, an analyst with the Centre for East European Policy Studies (CEEPS), Arnis Latišenko, gives a few examples of deception from the most popular news portal in Latvia, Delfi.lv. Latišenko selects the most striking and typical instances of deception created by Russia while dispelling the lies.

In Focus

One of Latvia’s success stories was the creation of investigative journalism centre Re:Baltica. For several years, Re:Baltica has been studying various issues of public interest. This includes the social and educational spheres as they relate to media. In the context of Russia’s information influence, Re:Baltica’s research on the influence of Russian media and compatriots as well as the channels used for it in Latvia – such as the study ‘Kremlin’s Millions’ on Russia’s support for radical Russian activists in Latvia and ‘Russkiy Mir’ about Russian media influence in Latvia – are particularly valuable. Another example of an investigation is the article ‘Sputnik’s Unknown Brother’, revealing the three Baltic Russian-language news sites known collectively as ‘Baltnews’ that are secretly linked to the Kremlin’s global propaganda network. ‘Small-time propagandists’ is one of the most recent investigative reports about the disseminators of fake news on the internet.

On Facebook, ‘Elves Unit’, led by the former Latvian diplomat Ingmars Bisenieks, started operating in 2017. The task of the unit is to uncover internet trolling (messages, fake accounts) that spread fake news on social networks. Volunteer ‘elves’ communicate with each other about trolls and suspicious news sites on a Facebook group exchange and post relevant publications on their Facebook pages. The ‘elves’ also hold informative seminars and invite communications and policy experts to share their knowledge. Another example of propaganda illumination is media expert Jānis Polis’ project ‘Internet propaganda in Latvia’ at the website ardomu.lv. Polis highlights examples of propaganda in Latvia mostly related to pro-Kremlin political forces. This list can be concluded with one example from the most popular Latvian newspaper, Latvijas Avīze, where a separate section, ‘LA Atmasko (LA Unveils)’, regularly reviews instances of deception and misrepresentation in Russian media.

In Focus

Another success story is the creation of the Baltic Media Centre of Excellence in 2015, which is a platform for the development of smart journalism in the Baltics, Eastern Partnership countries, and other regions. The aim of the centre is to promote the professional development of journalists and strengthen the competence of media users and critical thinking. The centre collects and generates knowledge about media environments and audiences in the Baltic and other regions. This is also the region’s most important player in the field of media literacy.

A successful project in the detection of Russia’s lies is the TV3 program series, ‘Melu teorija’ (Theory of Lies), which once a week analyses current examples of defamation in Latvia by interviewing communications and policy experts on Russia’s disinformation tactics. Understanding Russia’s informative influence methods is also enhanced by the NATO Strategic Communication Centre of Excellence, located in Riga. The centre is headed by an experienced Latvian defence and information-security expert, Jānis Sārts, who previously worked at the Latvian Ministry of Defence. The centre accumulates knowledge of Russian communication strategies and shares it with NATO member state governments.

Awareness of Russia’s use of trolls to influence Latvian media and the consequences of its compatriot policy is also enhanced by Latvian think tanks the Centre for International Studies, The Latvian Institute of International Affairs, and Centre for Eastern European Policy Studies. The creation of the Information Technology Security Incident Prevention Authority (CERT), which helps reduce risks from cyberspace in Latvia, has been of paramount importance in increasing internet security.

These examples illustrate Latvian civil society activity with the aim of decreasing the impact and spread of fake news and propaganda organised by the Kremlin. These projects are grassroots initiatives that include journalists, communications and political science researchers, and NGO activists. It should be noted that the experts and non-governmental sector have reacted to the problem faster than the state institutions, thereby demonstrating the very advantages and effectiveness of civil society.

Media literacy projects

Awareness of the need to improve media literacy has grown in Latvia in recent years. In February 2017, the Baltic Media Centre of Excellence launched the new ‘Full Thought’ initiative, aimed at promoting media literacy among Latvia’s 10th-12th grade high-school students and their teachers. The following is the training content created for the ‘Full Thought’ internet platform: six video presentations on various topics of journalism with examples and exercises for better understanding are provided by leading Latvian journalists and media experts free of charge.

In April 2017, the Ministry of Culture, in cooperation with Latvian universities and the British Council, organised a conference cycle on media literacy entitled ‘The Power of Media Literacy: How to Obtain and Use It’. It took place in Latvia’s biggest cities (Riga, Valmiera, Rezekne, and Liepaja) where domestic and British media practitioners and researchers outlined their vision while simultaneously analysing how to strengthen the media literacy of each individual and the public as a whole. In the summer of 2017, the Ministry of Culture presented the results of the research on media literacy to the Latvian population. They showed that about half the population of Latvia lacked understanding about how to properly evaluate media information.

The Office of the Nordic Council of Ministers in Latvia, in cooperation with the Safer internet centre of the Latvian Internet Association, hosted a seminar on media education for student capacity-building on October 3, 2017, at Rezekne Technology Academy. Guest speakers included Kadri Ugur, an expert on media education in Estonia, and Klinta Ločmele, an expert on media policy at the Latvian Ministry of Culture.

As can be seen from these few examples, projects promoting media literacy have been launched in Latvia at state institutions and expert levels. At the same time, it should be noted that media literacy has not yet been put into formal education programmes.

Conclusions and recommendations

The experts interviewed most frequently mentioned the poor capacity of state institutions related to the media sector. This is partly because of a lack of funding, which makes Latvian information space vulnerable. Ruduša, the director of the Baltic Media Centre of Excellence, and Roberts Putnis, the former director of the Media Policy Division at the Ministry of Culture of Latvia, pointed out that one of the reasons for insufficient public funding is the lack of understanding among the Latvian political elite of the special role played by independent and professional media in protecting democracy. The same circumstance was mentioned as the reason for the absence of a security strategy regarding the information space in Latvia.

The rejection of new media regulation aimed at putting more stringent standards of professional ethics on their activities as well as on the transparency of their actions and ownership by requiring the re-registration of all media working in Latvia was exposed as a legal impediment to this problem. Some experts pointed to the ethnically divided political environment as a factor in Latvia’s vulnerability vis-a-vis Russia’s information campaigns. On a narrower scale it was pointed out that the Latvian government was not sufficiently supportive of public and regional media. Also, among the still-unresolved issues is the disproportionately small use of the Latvian language in the national electronic media environment, which does not correspond to the ethnic composition of the population. Due to the unregulated free media market, there are two different information spaces that have developed in Latvia in terms of linguistic, geopolitical, and democratic traditions.

The most frequent recommendations made by Latvian media and communications science experts are to increase the capacity and authority of supervisory institutions while also improving regulation of the media sphere. The quality of content in the Latvian media space would be facilitated by regulation of internet media, which at present does not occur at all. Improvements in the regulation of the television and radio spheres should take place not only at the national but also the EU level. In 2017, the Baltic states prepared recommendations for changes to the EU ‘Audiovisual Services Directive’ to allow better monitoring and control of Russian television channels registered in the EU (such as those in the United Kingdom or Sweden) but which do business in another country such as Latvia. Another recommendation for the Latvian government is to extend support for media literacy projects through integration into the education system.

There are numerous good examples of how Kremlin-supported misinformation and disinformation campaigns can be undermined at the civil-society level in Latvia and in the actions of some state institutions, but generally there is still a lot to be done at the level of government strategy.

This strategy must apply to several Latvian political spheres: foreign policy, public diplomacy, defence, development of education, and media. Latvian foreign policymakers and implementers should be aware that the activities of Latvian media under Russian control are part of Russia’s official foreign policy, so, reaction to it is permissible and necessary. An assessment of Russia’s information influence in the context of national security is the responsibility of defence and security institutions. Such assessments and analysis are already ongoing. However, Latvia’s leading politicians and officials must take practical steps on education and media policies. In the education sphere, reform of the segregated (Latvian and Russian) system, inherited from the USSR, should be continued to strengthen the position of the Latvian language. This would promote the integration of minorities, thereby decreasing Latvia’s vulnerability to Kremlin-led disinformation. Latvian higher-level officials should make announcements on the crucial role of independent, professional and well-sponsored media in a functioning democracy. But the statement should be followed by practical steps to increase support for Latvian public media as well as for the legal and human resources capacity of monitoring institutions.