Introduction

Poland’s foreign policy and the political discourse after 1989 was built upon two fundamental goals: European and Atlantic integration (in the EU and NATO) and support for the independence and democratisation of its post-Soviet neighbours (Belarus, Lithuania, and Ukraine). The tensions between Poland and Russia in the 1990s were mostly based on Russia strongly opposing Poland’s membership in NATO. Despite this, Poland joined the alliance in 1999 and the European Union in 2004.

Since 2007, the government of Civic Platform tried its own ‘reset policy’ towards Russia with the launch of the ‘Kaliningrad triangle’, i.e., meetings between the foreign ministers of Poland, Germany, and Russia, and starting visa-free local border traffic (LBT) between two Polish voivodeships and the Kaliningrad region in 2012. However, the Polish ‘reset’ was later abandoned because of two main factors: the Russian aggression against Ukraine in 2014 and the long-term consequences and disagreements between the countries after the plane crash in Smolensk, Russia, in April 2010 that killed Polish President Lech Kaczyński and almost one hundred other high-ranking Polish officials, dignitaries, their family members, and crew.

The change of policy affected various areas. A year celebrating Polish culture in Russia in 2015 was canceled. When it comes to the military sphere, Poland strengthened its efforts to attract more NATO attention, as well as the deployment of U.S. troops to Central Europe. Mutual cooperation between Russia and Poland ceased once both the ‘Kaliningrad triangle’ meetings and the LBT agreement were suspended. Finally, economic cooperation also suffered because the sanctions on Russia and its counter-sanctions affected trade.

Polish officials and intelligence agencies acknowledged the role of Kremlin propaganda in Poland and Russian secret service activities in Europe. Back in 2015, the Polish Internal Security Agency published a report stating that the Russian intelligence services remained very active in Poland.In 2016, two events within the country were recognized as especially vulnerable to Russian secret service activity and internet trolls. One was the Warsaw NATO Summit. The other event was World Youth Day, a meeting of Catholics from across the world who came to see Pope Francis and celebrate their faith.

In 2017, the political situation in Poland was very tense. The judiciary reforms introduced by the government of Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS) were found to breach the rule of law by the European Commission and opposed by part of Polish society. What is more, Polish diplomacy had some problems finding a common language with its counterparts from Germany and Ukraine, and with representatives of the EU Commission and the European Parliament. In early 2018, Polish-Israeli relations also grew tense. Considering the Kremlin’s mechanisms, one may argue that political and diplomatic controversies inside and outside of Poland in 2017 became and still are fertile ground for manipulation and other disinformation activities.

Vulnerable Groups

Experts who follow and analyse the Kremlin’s strategy to influence and shape people’s opinions in various countries do not have a solid and unified explanation on whom to consider vulnerable to disinformation in Poland. The problem of a Russian-speaking minority, discussed as a vulnerable group in several other countries, for instance, in Latvia, Estonia, or some Eastern Partnership states, does not exist in Poland.

Russian TV is not popular in Poland since it is unavailable and most Polish people do not speak Russian at all or only at a very low level, so cannot be influenced by Russian-language media. This makes the potential threat of Kremlin manipulation much more blurred. Yet, one may distinguish some groups of people that for various reasons fall under this category.

One group seems to be vulnerable to direct Kremlin propaganda and consists primarily of older people nostalgic about the pre-1989 period when Poland was a satellite country of the Soviet Union.

‘This people often were well established in a previous system, working, for instance, in the security services’.

The group is a recent phenomenon on the Polish internet, and its late arrival is explained by two factors:

‘Those people are older than the average internet user and it took some time for them to learn how to use social media’ and ‘they stopped hiding their political views’.

In the past, the members of this group felt alienated, but once the low level of the political debate helped them to discover that other people may have similar political views, they started to be more open. The members of the group are disgusted with the weak West and praise a strong Russia. They hate the ‘fascist’ government in Ukraine, but admire the strong hand of President Putin. They also see anti-Polish conspiracies coming from the EU side, the Jewish community, and Germany.

Another vulnerable group consists of those whose beliefs are located at the extremes of the political spectrum, i.e., far-right and far-left. In Poland, the far-right is considered nowadays a much stronger and influencing position than the far-left. The main traits of far-right groups with regard to their vulnerability are closely interlinked with some key characteristics of the first group analysed in this chapter.

The anti-Ukrainian, anti-German, and anti-European attitude is a common thing among this group. They find the West (defined as the EU and the U.S.) as a place of moral decay and view refugees as an existential threat to traditional European values, a ‘Trojan horse’ of the Islamic revolution sent to Europe. It is worth a mention that this group consists not only of people who live in Poland but also Poles who live abroad, for instance, in the UK.

Although in opposition to the West, the members of the far-right movement do not seek any partnership with Russia. They may favour some aspects of the Kremlin’s internal politics (for instance, their imaginary perception of Russia protecting traditional values), but at the same time they often view Russia as a military threat to Poland. This group remains immune to direct pro-Kremlin propaganda, aimed at opposing a ‘good Russia’ with a ‘bad West’. But at the same time, this group remains susceptible to an indirect Kremlin narrative, whose goal is not to create a positive image of Russia in Poland but only to seek results beneficial to Moscow.

Finally, we should point out there are people who are prone to believe that politics is based on conflict and mistrust, rather than on mutual trust and compromise. In this category we could find a group that is vulnerable to anti-Ukrainian and anti-German propaganda or any other actions aimed to raise the tension between Poles and some other nations or institutions by presenting them as a threat to Poland, Polish interests, or as Polonophobes in general. This raising of tensions results in Poland’s losing its position internationally and slipping into self-imposed isolation. The antagonism was especially noticeable in regard to Polish-Ukrainian relations. Once on the fringes, the anti-Ukrainian agenda reached the mainstream of political discourse. Similar developments could be noticed recently with regard to Germany or the European Union.

It has to be acknowledged that the vulnerability of a certain group of people to the mentioned manipulation is not used solely by the Kremlin. The Polish political authorities (especially the government) stoke these tensions (willingly or not) in Polish society and try to take advantage of it. External actors, such as the Kremlin, are only secondary contributors or beneficiaries of the conflict.

Media Landscape

Freedom House in 2017 ranked Poland as partially free’, according to the Press Freedom Report, though a decade prior Poland had the status of ‘free’ . This status changed with the political developments in the country after the right-wing PiS came to power in 2015 and, among some other changes, weakened Polish democracy, limited journalists’ access to lawmakers in parliament, and appointed government-acceptable media managers to Polish public TV and radio broadcasters.

The ‘Media Pluralism Report’, a project co-funded by the EU and implemented by the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom at the European University Institute, assessed four dimensions and presented the main risk areas for media pluralism and media freedom: basic protection, market plurality, political independence, and social inclusiveness.

The scholars revealed that the following indicators are at high risk of violation in Poland: (a) media ownership concentration; (b) cross-media concentration of ownership and competition enforcement; (c) commercial and owner influence over editorial content; (d) political control of media outlets; (e) independence of public state media governance and funding; and (i) access to media for women. The report assessed the situation in the country after PiS came to power.

Once PiS took control in October 2015, a new law was passed terminating the contracts of the heads of public television and radio broadcasters. Journalists with state media (TV channels and radio) who criticized the new government and the political course it had chosen were either asked to resign or dismissed. There were also some journalists who resigned due to political reasons in protest against the political changes. As of February 10, 2018, according to the Journalism Society, 234 journalists had lost their jobs.

There are two main journalist associations in the country: the Association of Polish Journalists and the Journalism Society. As one expert said, they ‘produce statements’ about misconduct in media and concerning media regulation rather than focus on the defence and protection of freedom of information and open government.

On October 27, 2017, amendments to the Press Act were introduced almost unanimously. They obliged journalists to obtain the interviewees’ approval to publish their responses. That made it impossible to publish an interview in Poland without the advance consent of an interviewee. The European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, in its decision regarding Wizerkaniuk v. Poland in early 2011, condemned the provisions requiring the authorisation of interview responses and found them to be a violation of the right to freedom of expression.

Grzegorz Piechota, a research associate at Harvard Business School, warned that the current government, driven by anti-German sentiment, might change regulations on foreign investment in the media field (so-called ‘re-Polonization’). This could affect the ‘investments of Ringier Axel Springer [the owner of the largest internet portal, Onet, and the largest tabloid, Fakt], and Verlagsruppe Passau [the publisher of the majority of the regional newspapers and web portals across Poland via its subsidiary Polska Press]”.

At the same time, investigative journalism in Poland is underdeveloped. One of the experts informed that there are just six or seven professional investigative journalists in the country and they are mostly concentrated in Warsaw, while there is almost no investigative reports from the regions. The media outlets have no additional budgets to allow investigative reporters to spend months working on a piece. There are two kinds of investigative initiatives created by journalists in Poland: the Reporters Foundation (Fundacja Reporterów) and OKO.press. Both mostly rely on foreign funding and crowdfunding.

Meanwhile, it is worth mentioning that the British government ‘is ready to improve the UK-Poland cooperation to counter the Russian disinformation in the region [emphasis by the author], including some new joint strategic communications projects’. The production cooperation between the BBC and Belsat TV (a Polish state-funded TV channel broadcasting in Belarus) is one such initiative. The overall sum of the cooperation equals 10 million GBP, with the UK side contributing 5 million GBP and Poland expected to provide a matching amount.

To sum it up, the media environment in Poland is highly politicised and divided. The significant change happened after the presidential elections in 2015, and the situation in media now is deteriorating. The national level of political propaganda and disinformation appears to be a threat and a topic for public discussion more often than any foreign state or party influence.

However, none of the Polish media outlets (TV, radio, print, or digital) obviously relay Kremlin-influenced narratives or messages, unlike those found to be published by individuals in some closed or public groups of special interest on Facebook or by thematic GONGOs, such as the Warsaw Institute Foundation.

According to the Public Opinion Research Centre, ‘the Poles usually get the inland and world news and other information from TV (64%) and then from the internet (about a third of them—21%—as frequently as from TV)’. Only 8% of the respondents use radio as the first source of information and 4% of them use print media.

The public survey recently conducted in Poland by the International Republican Institute shows that the population uses public and commercial TV (36% and 32%, respectively) to get political news while only a quarter of the respondents (21%) use online media. The senior group (60+) prefers public (55%) and commercial (29%) TV, while younger people (18-29) frequently use some online sources (43%). A third of Poles uses social media as a source of daily news and almost half never uses any alternative source of information, only leading media outlets.

It is interesting to note that the 2018 Edelman Trust Barometer, assessing the level of trust in traditional and online-only media compared to search engines and social media platforms in Poland, says that Poles trust them almost equally (54% vs. 51% comparatively). Basically, it means that people equally trust online media (published by journalists) and social media (the opinion of a particular person, usually not a journalist). During an in-depth interview, it was said that the growing number of closed groups on Facebook might be a source of manipulation and disinformation dissemination, where it is more difficult to confirm the identities of accounts holders or the initiators of such groups.

The 2017 Reuters Institute Digital News Report underlines, nevertheless, that the media environment in Poland is ‘polarised and increasingly partisan, (while) the news media in Poland continue to be trusted by the public’. According to the 2017 Digital News Report, 53% of the population uses Facebook as a source of information; 32% prefers YouTube, and 10% chooses Facebook Messenger for getting news. One of the interviewed experts also highlighted this tendency as one of the ‘pitfalls’ on the way to critical thinking development, and the daily need for diverse sources of objective information.

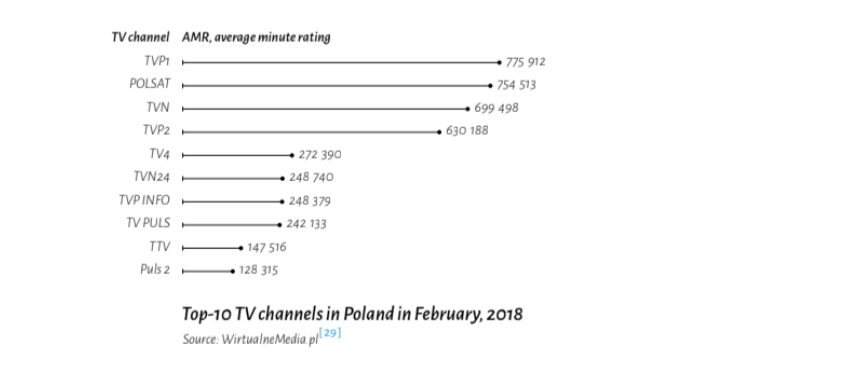

The Polish TV market is divided between the leading three conglomerates: the public broadcaster TVP, the private broadcaster POLSAT, and the International Trading and Investments Holding SA Luxembourg Group ITI. There are also some minor TV channels that work as joint ventures: Canal+, HBO, EuroSport, Discovery, MTV Poland, and others.

The leading web portal about media and media monitoring is WirtualneMedia.pl. It assessed the 150 most popular TV channels in 2017 in Poland. TVP1, TVP2, and TVP Info belong to the public broadcaster (TVP); Polsat and TV4 belong to the private broadcaster (POLSAT); TV Plus and Puls2 are owned by Telewizja Puls, a Polish private commercial channel mostly broadcasting entertainment, series, and documentaries; and TVN, TVN24, and TVN7, owned by the ITI Group (since March 6, 2018, TVN group is owned by Discovery Communications, a U.S. company).

The Polish Institute of Media Monitoring ranked the most opinion-forming TV channels in Poland. Of these, TVN24 and TVN are owned by the ITI Group and appeared in the top-10 TV channels list, TVP Info belongs to the public broadcaster (TVP), POLSAT News to the commercial broadcaster Polsat, and TV TRWAM is a regional TV channel owned by the Lux Veritatis Foundation and broadcasts social, religious and musical programmes.

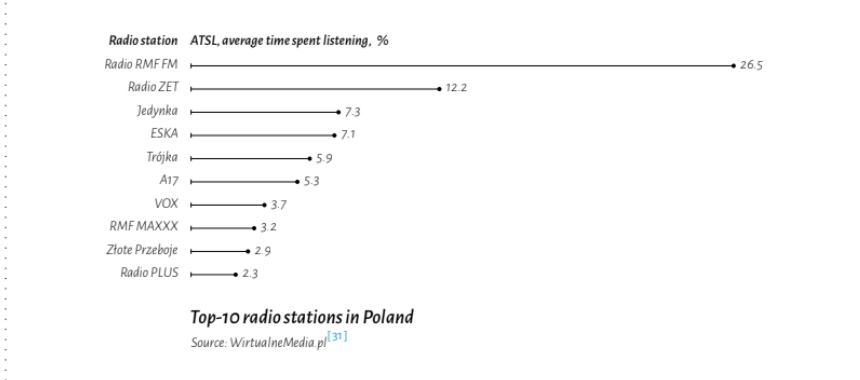

The Polish radio stations are split across ownership. Among those that belong to public radio broadcasters is Polskie Radio (both FM and digital), commercial broadcasters, including the leading ones from the Bauer Media Group, Lagardere (Eurozet), Grupa ZPR Media, Time Group, and Agora, and non-commercial stations, such as the 20 or so regional Catholic stations, including the biggest, Radio Maryja.

The top-10 radio stations include mostly commercial stations (ESKA, RMF MAXXX, Złote Przeboje, Radio Plus, Radio WAWA, Meloradio, Radio Pogoda, Rock Radio, and ChiliZet), and A17, online radio stations. It is important to emphasize that the popularity of Polish media stations varies depending on the region.

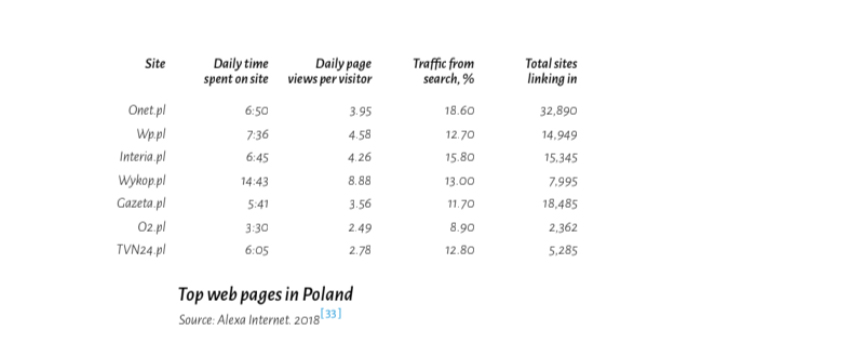

Online media is a growing segment in Poland, with two types of media identified. There are web portals that offer some news services together with a web-hosting service, email, search engine, and online chats. This is a hybrid model of media, combining both online and news services. According to the ‘Online Advertising in Poland: Development Perspectives 2016/2017’ report, spending on online media maintenance nearly doubled from 2011 to 2017 (from 16% to 30%).

The second type of digital media is subscriptions to print media websites. This is a promising alternative for traditional media losing readership from vending. The largest print media editions provide online subscriptions (with the content identical in print and online), as well as .mobi (for MobiPocket Readers and Amazon Kindle Readers) and .epub (for smartphones, tablets, computers and e-readers) versions. The top-5 media editions leading in online subscriptions in 2017 were Rzeczpospolita (11 300 online subscriptions), Dziennik Gazeta Prawna (10 722), Puls Biznesu (3 373), Parkiet Gazeta Giełdy (1 729), and Gazeta Wyborcza (1 661).

In focus

Radio Hobby

Radio Hobby has been broadcasting since the end of 2008 in Warsaw and its closest suburbs—Bialoleka, Targowek, Praga Polnoc, Tarchomin, Legionowo, Secock, Wolomin, and Radzymin (as the ‘Foreigners in Warsaw’ report revealed, these areas are inhabited by immigrants from neighboring countries to the east: Belarus, Ukraine, Russia. The target audience is described as men aged 25-50. The radio transmits contemporary music, local business (e.g., how to start your own business and became an entrepreneur), share job vacancies from the regional employment department, promotes an eco-friendly and sustainable lifestyle, and has a special programme for drivers. Every day at 9 p.m., the station transmits a Russian cultural and information programme prepared by Radio Sputnik, promoting the Kremlin interpretation of world events. The editor of the station declined to comment.

Source: Polskie fejki, rosyjska dezinformacja. OKO. Press tropi tych, którzy je produkują.

Legal Regulation

There is a deficiency in the specified legal acts about information security and information threats in Poland. Several corresponding provisions can be found in some legal acts and regulations about particular government offices. It should be noted that in the security documents, ‘information security’ is frequently understood as ‘cybersecurity’. There are two key security documents that require more attention to the information security issue.

The ‘Concept of Defence of the Republic of Poland’ (published in May 2017) finds the ‘aggressive policy of the Russian Federation’, ‘including the use of such tools as disinformation campaigns against other countries’ as one of the main threats and challenges. The Concept does not contain any precise developments or tasks regarding information security.

The ‘National Security Strategy’ (published in November 2014) interprets information security as part of cybersecurity efforts (for example, article 84 describes cybersecurity as including ‘the information fight in cyberspace’; article 85 explains ‘information security’ as the ‘security of classified information (…), ensuring the information security of the state by preventing unauthorised access to the classified information, and its disclosure’).

The Strategy underlines that the Polish Armed Forces (Siły Zbrojne RP) are responsible for ‘the development of the operational capabilities of the Polish Armed Forces’ including the raising of the ‘level of training and the ability to use professionally advanced (…) information tools’ (article 117).

The Parliamentary Commission of National Defence pointed out in February 2015 that the National Security Strategy should be coordinated ‘between the Ministry of Digital Affairs and the military structures’. It seems that no further suggestions were made. The new National Security Strategy is now being drafted by the National Security Bureau (BBN). As the head of the BBN, Paweł Soloch, said, ‘there is a need for system changes’ now since the Strategy was drafted before Russia’s annexation of Crimea, when some new challenges emerged, including hybrid warfare, cyberattack, information warfare, as well as asymmetric terroristic threats’. Soloch highlighted that all these menaces are to be included in the new draft.

The ‘Doctrine of Information Security’ was started as a draft in 2015 by the BBN as a response to the increase in hybrid threats, propaganda, disinformation, and psychological influence operation by foreign states and non-state actors. The Doctrine is supposed to be the key document clarifying the scope of responsibilities and the mode of cooperation and coordination between the government, private institutions, and citizens. The Doctrine is still in the drafting phase. According to the draft, the Polish strategy in information security, among other things, should include the ‘creation of compatible media (radio and TV)’ for minorities in Poland that can be a match for Russian media targeting those groups, as well as the facilitation and support of broadcasting efforts in Belarus (article 31). The document says that the detailed tasks will be developed in the ‘Political and Strategic Defence Directive’, the ‘Strategy of National Security Development’, and some other tactical regulations.

Institutional Setup

The expert said that the

‘Polish government does not openly communicate on the information security issue’.

While working on this report, six government institutions (listed below) were contacted by with an in-depth interview request, but no communication or response was received. Therefore, the information provided in this section is based on the LEX Omega (by Wolters Kluwer Polska) and open sources.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs ensures the ‘efficient and continuous circulation of the critical information in the ministry and its foreign branches, in particular, a) acquires the critical information from all available sources, including the constantly monitored media; b) verifies and processes the critical information for the purposes of the recipients’ competence; and c) immediately relays the critical information to the competent addresses in the ministry and its foreign branches, as well as, if necessary, in other public administration institutions’ (and the Consular Department is responsible for this, article 40). The Polish MFA is under internal political attack nowadays, first of all being criticized for the politically questionable policies towards many countries, with the most burning ones towards Ukraine (‘we are experiencing the biggest crisis in the relationships from the Khmelnytski Uprising’, said Paweł Kowal, the former Vice-Minister of the MFA) and Israel (‘the relations are broken, wasted’, commented Bogdan Borusewisz, the deputy speaker of the Senate). The recently published article in Polityka magazine’s print version, titled ‘Zaginione ministerstwo’, says that ‘barely 40-50 among 2 500 MFA servants graduated from Russian universities’.

The scope of the responsibilities of the Ministry of National Defence does not put any special emphasis on information security. The Department of Strategy and Defence Planning is, among others, responsible for the ‘non-military defence preparations programming, and organising of the operational planning process in the public administration bodies for the external security threat and wartime.

eTh BBN (Biuro Bezpieczeństwa Narodowego, or National Security Bureau) is the government agency working under the president of Poland regarding national security issues and providing research and organisational support to the National Security Council, the constitutional advisory body of the president on internal and external state security. The BBN , among other tasks, is responsible for ‘monitoring and analysing the strategic environment of national security (both internal and external)’, and ‘developing and reviewing the strategic documents (concepts, directives, plans, and programmes) in the field of national security (…)’.

It is important to note that the BBN defines ‘information security’ as a ‘trans-sectoral security area, the content of which refers to the information environment (including cyberspace) of the state; a process aimed to ensure the safe functioning of the state in information space through the domination of its own internal domestic infosphere and effective protection of the national interests in the external (foreign) infosphere. This is accomplished through the implementation of such tasks as: ensuring the adequate protection of information resources, and protection against hostile disinformation and propaganda activities (in the defence dimension) [author’s emphasis] while maintaining the ability to conduct offensive actions in the area against potential opponents (states or other entities). These tasks are laid out in the strategy (doctrine) of information security (operational and preparatory), and for them to be implemented, the appropriate information security system is maintained and developed’.

The Internal Security Agency is responsible for the ‘recognition, prevention and detection of threats to security essential from the point of view of the continuity of the state, functioning of ICT systems of public administration bodies, or ICT network systems covered by a unified list of facilities, installations, devices, and services included in the critical infrastructure’ (para 2a, article 5) and ‘obtaining, analysing, processing, and transferring to the competent authorities information that may be essential for the protection of the internal security of the state and its constitutional order’ (article 5, para 4).

The Foreign Intelligence Service, a Polish secret agency tasked with gathering public and secret information abroad, is responsible for ‘obtaining, analysing, processing and transferring to competent authorities information that may be essential for the protection of the internal security of the state and its constitutional order’ (article 6, para 1).

The Ministry of Internal Affairs and Administration (MSWiA) is the public administration body responsible for the public administration and internal issues, as well as issues connected with national and ethnic minorities. The Department of Public Order is responsible, among others, for the supervision of activities connected with the protection of people and public safety. This is the only department that might be responsible for information security in the ministry.

The State Protection Service (SOP) was created on February 1, 2018, in compliance with the ‘Law on State Protection Service’, introduced on December 8, 2017, and reporting to the MSWiA. The SOP restructured the Office of Government Protection, which was deemed to be ineffective in many issues. The service is responsible (article 3), among other tasks, for dealing with crimes against security, crimes against communications security, offenses against freedom, crimes against honour and physical integrity, crimes against the public order, attacks and active assault against persons, the recognition, prevention, and detection of crimes committed by SOP officers, and conducting pyrotechnic and radiological reconnaissance of the premises of the Sejm and Senate. According to the law, the SOP can use secret cooperation, among others, with an editor-in-chief, journalists, and other people involved in publishing while implementing their goals and objectives (article 66). This cooperation is possible after obtaining the consent of the head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Administration.

The Institute of Information Activities at the Academy of War in Warsaw. The institute is responsible for academic and analytical research activities in the field of information security for the purposes of the academy, the Ministry of National Defence, and the Polish Armed Forces, including training for operational, tactical, and strategic specialists and experts in the field of the military and public administration institutions. The institute conducts regular meetings and training, including some guest lectures on the issues, such as a recent one by Dr Sergey Pakhomenko (Mariupol State University, Ukraine) or the conference called ‘Russian resources in the Intermarium and the Possibilities of their Employment in the Infowars Against Countries in the Region’.

There are also some special bodies that focus on strategic communication: the Government Information Centrum, which is responsible for online and other media communications of the highest government institutions; the Interministerial Team for the Promotion of Poland Abroad at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which ‘coordinates tasks of the respective ministries regarding such issues as the protection of the good name of Poland […] (and) drafting a coherent and comprehensive strategy for the promotion of Poland abroad’, as well as the Chancellery of the President. The scope of the responsibilities of the government spokespersons are defined by a special regulation.

To sum up, information security in Poland is a rather legally and institutionally underdeveloped issue. Poland might be categorised as poorly resilient and highly vulnerable to information threats. The developed, ostensibly institutional system lacks clear coordination in the field of information security. More attention was given to cybersecurity rather than to information security. There are two main cybersecurity documents that support this argument: the draft ‘Cybersecurity Strategy for 2016-2022’, and the ‘Cyberspace Protection Policy of the Republic of Poland’. The draft document also introduces the establishment of the Cybersecurity College and a Government Representative for Cybersecurity. In March 2018, the Polish prime minister established a new position of Government Representative on Cybersecurity, who will report to the Ministry of National Defence.

Digital Debunking Teams

Poland is only at the beginning of the road in the process of developing initiatives that will be primary focused on fact-checking. Arguably, the most recognizable one is OKO.press, an internet portal gathering journalists whose job is mostly to verify the statements made by politicians and other public figures. OKO.press journalists prepare both short comments and longer analyses regarding the current political situation in Poland and try to cover all important topics, including internal developments and international relations between Poland and other countries and institutions. OKO.press was started by five journalists and is financially supported by Agora Holding (whose most well-known liberal media outlets are Gazeta Wyborcza and Radio TOK FM), Polityka (the leading liberal weekly in Poland), and private donors. Currently, the project runs on donations and is published by the Centrum of Government Control ‘OKO’ Foundation (Fundacja Ośrodek Kontroli Obywatelskiej ‘Oko’). All the content, including the analyses, investigative reports, and fact-checks, produced by OKO.press is available to its readers for free and is visited by around 2 000 visitors daily (93% from Polish IP addresses), with 46% of the visitors being redirected from social media and 30% being direct traffic.

Another fact-checking initiative is Demagog. Its journalists work as volunteers and their job is solely to verify Polish politicians’ statements. By comparing their speech with factual information, Demagog’s journalists verify whether the politician has told the truth or misled the audience (intentionally or unintentionally). The initial idea for the project came from U.S. platforms FactCheck.org and PolitiFact.com. The students from Masaryk University in Brno (Slovakia) first launched a similar platform called ‘Demagog’ in 2010, and later others were started in the Czech Republic, Hungary, and in 2014, in Poland. Demagog Poland launched a media-literacy project called ‘Fact-Checking Academy’. The academy, supported by the U.S. embassy in Poland, aims to raise media literacy in schools and among young people through workshops and lectures.

The Observatory of Media Freedom is a programme launched by the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights and Article 19 in 2008. Currently, the Observatory is running a project called ‘Monitoring of Threats to Free Media in Poland and Strengthening of Local Media Control Function’. The project is supported by the University of Warsaw (Law and Administration Department) and Maria Curie-Skłodowska University (Political Science Department). Its programme aims to raise awareness about media freedom and independence in Poland, including stimulation of public debate on the issue, some educational activities (citizen journalism), and media monitoring, including media-regulation monitoring as well.

Poland, however, does not have a well-developed market of fact-checking initiatives and debunking teams that deals with Kremlin disinformation. There are some initiatives implementing activities aimed at understanding how Kremlin influence actually works in Poland, and the actions of these initiatives are also worth mentioning.

The famous Stopfake initiative, responsible for debunking fake news about Ukraine has a version in Polish. Stopfake in Poland works to provide the Polish audience with examples of fake or manipulated news published by pro-Kremlin media outlets in Russia or in Russian-language media in other countries, such as Ukraine. Poland–Ukraine relations also happen to be a subject of such manipulated stories, with fake news coming mostly from the Russian media outlets and very rarely from Polish sources.

Another initiative, the Infoops, researches manipulation of information about Poland in foreign propaganda. That is a project initiated by the Polish Cybersecurity Foundation. One of its goals is to use social media while communicating about disinformation cases in Poland. The Cybersecurity Foundation launched a Twitter account, @Disinfo_Digest, aimed at providing daily reporting on the fake news produced by the Kremlin and other sources. The reports are not limited to Poland but also include some fake news spread in other countries.

The Russian Fifth Column in Poland is a Facebook platform whose authors regularly post information about the connections between Polish activists, politicians, and members of academia with some people from Russia and other countries who spread a pro-Kremlin narrative. The editors of Russian Fifth Column in Poland gather and reveal evidence showing examples of promoting anti-Ukrainian, anti-NATO, and anti-EU attitudes and explain their connections to the pro-Kremlin surroundings.

The Centre for Propaganda and Disinformation Analysis is an NGO aimed at raising awareness about manipulation and propaganda mechanisms, and explaining the threats of propaganda to national security. The centre already has published some analysis on information security and disinformation, including the report ‘Russian Disinformation War Against Poland’, and a policy paper, ‘How to Build Information Resilience of Society in Cyberspace while Countering Propaganda and Disinformation’.

Besides the described initiatives, one should mention the individual reports and analysis prepared by Polish experts or journalists aimed at debunking Kremlin disinformation in Poland, such as the reports ‘Threat of Russian Disinformation in Poland and Ways to Counteract it’ ‘Russian Soft Power in Poland. The Kremlin and Pro-Russian Organisations’ or ‘Information Warfare in the Internet’.

In Focus

Adam Kamiński’s Fake Facebook account

A person who called himself Adam Kamiński created a Facebook account, stating that he was the editor of Niezależny Dziennik Polityczny(Independent Political Magazine). He had 1 624 Facebook friends, and the deputy minister of National Defence was among them. This person used to publish and share articles from Niezależny Dziennik Polityczny but also some fake information or disinformation about the Ministry of Defence as well. In fact, Niezależny Dziennik Polityczny, in a comment to journalists, said that the person named Adam Kamiński did not work for the magazine and it had no record of him. The Facebook friends of Kamiński reached by the journalists told them they had never seen this person. When the journalists contacted Kamiński, he rejected to meet in person or have a Skype talk and responded only electronically. This case was revealed and investigated by Patryk Szczepaniak and Konrad Szczygieł, journalists of Oko.press, who found out that the profile picture of Adam Kamiński was stolen from a Lithuanian orthopaedist named Andrius Žukauskas.

Source: Polskie fejki, rosyjska dezinformacja. OKO.Press tropi tych, którzy je produkują.

Media Literacy Projects

The interviewed experts confirmed the alarming low level of critical-thinking skills among young people. The primary and higher education curricula demonstrate a lack of special blocs on critical thinking and media literacy, as well as a lack of qualified teachers who can teach those skills. The introduction of such courses is mostly bottom up from civil-society organisations. Such programmes are divided according to the age of the target audience: from schoolchildren to young activists, and from those who do not have any previous knowledge and experience to those who would like to enhance their skills and share the expertise.

Olimpiada Cyfrowa is a project launched in 2002 by the Modern Poland Foundation (Fundacja Nowoczesna Polska) and funded by the Ministry of Education and Sport and Ministry of Culture and National Heritage. The project targets secondary school pupils to raise their awareness about media skills and literacy, including critical analysis of information, media ethics, the language of media, and internet security. The project also motivates teachers to discuss security issues, the internet, media, and digital education in social media.

The Cybernauci project is aimed at training skills to be safe and secure on the internet. The project was launched by the Modern Poland Foundation in cooperation with Collegium Civitas. Its target audience is described as schoolchildren, their parents, and teachers. The project’s team organises various workshops to develop the pupils’ skills and competences on the safe use of online sources, soft skills for parents on how to talk with their children about rules on internet usage, and how to use digital resources in education for teachers.

The Orange Foundation (Fundacja Orange) is a non-profit organisation created in 2005 by the Polish telecommunications provider. The foundation aims to develop digital education, including children and youth’s media skills development. The educational competition ‘Safe Here and There’ (Bezpiecznie Tu i Tam) was launched by the foundation in 2016 to popularise safe behaviour on the internet and new media. This online course is available for free online.

The Gogito 21 project was launched in 2016 by the Centrum of Innovative Education to strengthen schoolchildren and teachers’ critical-thinking skills. The project was in the form of a competition. Any school could register a representative (a teacher) to form a club of pupils. Every competition participant received a handbook, could attend two webinars, and have mentor support. The club had to plan and implement an information campaign in media and make a short video. These materials could be awarded with a prize for the best performance.

In 2018, Facebook will open a new digital media hub in Poland. The hub will offer ‘training in digital skills, media literacy and online safety to groups with limited access to technology, including older people, the young, and refugees’. Similar hubs were opened in Nigeria and Brazil.

On February 16-18, 2018, a hackathon was held for the development of a ‘natural shield when it comes to common manipulation techniques on the internet, such as fake news, phishing, clickbait, cyber-extortion scams, etc’. Its participants were educators and activists who in 48 hours had the challenge of developing several ‘apps, games and quizzes’ in groups composed of 3-5 people, including a programmer, an educator, some journalists, a media expert, a copywriter, and an activist. A similar initiative by the Warsaw Legal Hackers, under the theme ‘Fake News. How to Catch Electronic War Dogs by the Tail?’ was held on March 14, 2018.

Conclusions

The conducted analysis of the societal vulnerability and government resilience to Kremlin disinformation in Poland revealed the complexity and multifacetedness of the situation. The interviewed experts and national politicians confirm that the Kremlin’s influence in Poland is rather ‘intangible’ and cannot be described as a mere production of ‘fake news’ or any ‘manipulated content’. In many ways, the Kremlin takes advantage of situations that emerge rather than creates or triggers it. In the previous year, Poland was involved in an array of internal and external tensions that heated up the negative atmosphere of relations with Ukraine, Germany, the U.S., Israel, and the EU. Those tensions established fertile ground for foreign manipulative influence in Poland.

At this stage, Poland has limited expertise and capacity to combat such vulnerabilities, as well as a low level of resilience to Kremlin disinformation operations or foreign manipulative media influence. A trend observed among many politicians is a growing tendency to call every information they disagree with ‘disinformation’ or ‘fake news’, no matter if the information is true or not. As a consequence, instead of fighting disinformation, some Polish politicians provoke or encourage it.

The underdevelopment of information security institutions (namely, the absence of a specified scope of responsibilities and power-sharing), the lack of cooperation and sustainable partnership among existing ones result in a high level of susceptibility to Kremlin-backed or other third-party information influence or targeted operations.

The lack of well-defined, comprehensive, clearly explained division of responsibilities and authority in legislation and regulations exacerbates Poland’s vulnerability in the information security field.

The country’s media environment faces a lot of challenges as well. The short-lived interest in information on the internet causes journalists to publish their materials quickly, sometimes without double-checking their sources and facts. While editorial desks struggling with a lack of funding, unable to invest in the investigative journalism, a well-functioning fact-checking body, training to strengthen journalists’ skills and competences, continuous media-monitoring, the launch of well-established media-literacy programmes, and other digital-debunking initiatives must be supported and strengthened in Poland on all levels.

The government institutions, as well as the media outlets and civil-society organisations are still in need of stronger cooperation, but, first and foremost, a clear comprehension of the current information threats. In this regard, it is not only the political elite that must be engaged but the civil sector and media should be ready to share their expertise and knowledge and work in concert.

To increase analytical expertise in the information security field and make civil-society organisations more active in the digital-debunking and fact-checking, the development of effective and well-functioning communications channels is both desirable and required.

Recommendations

To Government Institutions

- Establish a platform for regular meetings of government officials, experts, and civil-society representatives in the information security field. The experts from analytical institutions, academia, and civil-society organisations can share with and update government institutions on the most recent developments in the field, share the best international and national practices, and propose some new approaches and solutions.

- Introduce changes into the school and higher-education curricula and add obligatory media-literacy courses. Programmes, handbooks, and other materials prepared for established national civil-society organisations and initiatives should be used for this task too.

- Launch continuous training and sharing of information-security best practices, as well as the related workshops for the government officials and civil officers to strength their expertise and build the capacity to respond to the challenges. The international experience might be used for this task too (for example, from Estonia or Latvia).

- Support media-literacy projects for all age groups. Thus, civil-society organisations and initiatives will be able to provide their expertise and experience on this issue.

To Civil Society

- Cooperate on a regular basis in the exchange of expertise and experience with international civil-society organisations and actors who have extensive experience and involvement in local media-literacy projects and digital-debunking initiatives. Other countries’ experience can extend and expand the view of the country’s weaknesses.

- Maintain cooperation with the local civil-society platforms and actors to enhance the level of societal resilience to media manipulation and disinformation.

- Conduct education activities for all age groups on basic media literacy and media-manipulation awareness. Build up an experienced and professional team of trainers and experts able to conduct on-demand training and workshops for government officials, civil-society representatives and media people on advanced media literacy, psychological media influence, and manipulation.

To Media

- Support investigative journalism initiatives and programmes, with a focus on the local level. Engage experienced international and mature national investigative journalists to share their expertise and build new skills and competences of Polish investigative and digital journalism.

- Conduct training and workshops on media ethics and journalism standards on a regular basis.

- Launch editorial fact-checking boards in leading media outlets.