Established in 1992, diplomatic relations between the two countries were not especially well-developed, although gradual rapprochement was happening. Following the downing of the MH-17 flight by the Russian forces in the East of Ukraine, the bilaterals received a brand-new impetus for development as Ukraine and Australia both were the injured parties to the case. It was then that it could be clearly seen that events happening in one country could have implications and influence the interests of another country, even if both are divided by thousands of miles. In 2022, Australia became one of the major donors to Ukraine in the aftermath of Russia’s full-scale invasion of the country, being the second largest non-NATO contributor. It has also imposed a significant number of sanctions aiming to hold Russia accountable for international law violations.

For Australia, the regional configuration of powers is among the primary security concerns. In particular, rising China prompts Australia to strengthen its security alliances. Thus, Ukraine and Australia have a common interest in upholding the rules-based international order and countering threats from increasingly belligerent neighbours. Still, China is Australia’s biggest trade partner. Consequently, Ukraine’s example in tackling economic dependencies might be crucial.

In bilateral relations, the cooperation between Australia and Ukraine was marked by the uneven trade in the years following Ukraine’s regaining independence. The immediate aftermath of the full-scale invasion was the fall of Ukraine’s exports to Australia and the rise of Ukraine’s imports from there signifying the destructed value chains and the need for an external supply of goods. Australian coal exports became one of the main ways of economic cooperation, helping Ukraine survive through the brutal winter of 2022/2023, with Russia attacking all major power facilities.

Importantly, the cooperation between Ukraine and Australia is not limited to economic cooperation. There is room for cooperation in the science sphere, in counteracting cyber threats, developing the military-industrial complex, and testing existing weapon samples in real-life battles.

A crucial element in bilateral relations is the Ukrainian diaspora in Australia. With about 38,000 Ukrainians living now in Australia, it is important to develop cultural cooperation. For Ukraine, it means maintaining ties with the Ukrainians abroad and finding ways to integrate them into Ukraine’s social and political life, as well as seeking their help in promoting the country’s interests.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

A BRIEF HISTORY OF UKRAINE’S RELATIONS WITH AUSTRALIA IN 1991-2014

BILATERAL RELATIONS BETWEEN 2014 AND THE PRESENT TIME

- Political cooperation

- Trade Relations

- Ukrainian diaspora in Australia

CURRENT SITUATION AND COOPERATION POTENTIAL

- Current regional setup and challenges

- Opportunities for Cooperation

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Political cooperation

- Security cooperation

- Economic cooperation

- Social cooperation

.

INTRODUCTION

The Russian invasion of Ukraine, first in 2014 and then in 2022, has drastically changed Ukraine’s perspective on its bilateral relations. Having found itself in a position where the international community support, both from the so-called Global North and Global South, is of crucial importance, Ukraine started building and elaborating its international relations with the countries that previously not always have been the focus of its attention. This also applies to developed middle powers, with which no strong and sustainable relations have been developed due to the geographical location and the then-priorities of the foreign policy.

Located on the other side of the world, twelve thousand kilometres away, Australia was considered a distant country, with the potential for cooperation being rather small. This perception started to change due to Ukraine’s rising awareness of the scale of globalisation, the interconnectedness of the states, and the importance of securing the support of not only the European powers and the US.

Undoubtedly, Australia’s involvement in Ukraine’s case was triggered to a large degree by Russia shooting down the MH17 plane in 2014, with many Australians aboard. Since then, the cooperation has remarkably evolved, and Australia became one of the largest non-NATO contributors to Ukraine’s defence in times of full-scale Russian aggression. At the same time, the Ukraine-Australia bilateral relations still have the potential to evolve and become more profound in light of the common challenges the two nations face.

This paper strives to delve deeper into the bilateral relations between Ukraine and Australia and explore opportunities to enhance the existing cooperation. The paper starts by studying the retrospective of Ukraine’s relations with Australia since Ukraine regained its independence and up to the present day.

The study further examines the current political and security situation in the world, both in the Indo-Pacific and globally, focusing on the events and trends relevant to Ukraine and Australia in terms of their cooperation. The paper also explores the economic situations in Australia and Ukraine, as well as the challenges and common implications of this. An important part of this research is to outline key opportunities for cooperation between Ukraine and Australia in the named spheres.

Complemented with an analysis of the Ukrainian diaspora functioning in Australia, the paper then provides policy recommendations for Ukrainian officials working in the field of foreign affairs to ensure cooperation between Ukraine and Australia is organised with a deep understanding of a global context and mutual benefits that it could bring in the rapidly evolving modern-day environment in Ukraine and globally.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF UKRAINE’S RELATIONS WITH AUSTRALIA IN 1991-2014

To understand the dynamics of Ukraine-Australia relations, it is necessary to look into the history of bilateral relations – whether it is upward or downward. For the purposes of this analysis, the history of Ukraine’s relations with Australia is divided into two main periods: (1) 1991-2014 – from Ukraine’s regaining its independence to the start of the Russian invasion in 2014; (2) 2014-present – the period of the hybrid Russia aggression against Ukraine, as it was characterised with the increasing degree of cooperation between Ukraine and Australia and following the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine that served an additional boost to the bilateral relations between Kyiv and Canberra.

Australia recognised Ukraine’s independence in late 1991 and sent a note to the newly established Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, expressing a wish to establish diplomatic relations. Importantly, Australia indicated that no permanent Embassy would be opened in Kyiv and asked for the Australian Ambassador to Moscow, Cavan Hogue, to be able to serve as the non-resident Ambassador to Ukraine. In March 1992, Ambassador Hogue became the second ambassador (after the German ambassador) to have presented his credentials to the President of Ukraine, Leonid Kravchuk. Notably, even before formally recognising Ukraine’s independence, an Australian Senator and Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade, Gareth Evans, visited Ukraine and announced that Australia would establish a consulate in Ukraine headed by the honorary consul. Minister Evans stressed that Australia is looking forward to economic cooperation and collaboration in the educational and scientific sphere; he also mentioned the future non-nuclear status of Ukraine.

From these first interactions highlighting the beginning of the Ukraine-Australia bilateral relations, it could be argued that, initially, the Australian government took the “waiting position”, being neither willing to be too proactive right from the start nor to write Ukraine off immediately. It can also be seen that Ukraine is not yet considered a sufficiently important country despite being a large state geographically and population-wise. Russia was still seen as a master power in the region, a centrepiece of the diplomatic relations with its ex-colonies.

Simultaneously, Ukraine has not been very active in developing bilateral relations with Australia in the first years after regaining independence. Only in the late 1990s did Ukraine first transform the honorary consulate in Melbourne into the consulate general in Sydney and later established the Embassy in Canberra. Eventually, the Ukrainian Embassy in Canberra was opened in 2003. Yet, it was not till 2014 that Australia established a resident Embassy in Kyiv.

BILATERAL RELATIONS BETWEEN 2014 AND THE PRESENT TIME

Political cooperation

Following Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea in March 2014 and the subsequent invasion of Ukraine’s Eastern territories, Ukraine became one of the centrepieces of global politics. It would not be an over-exaggeration to state that the turning point for bilateral relations was the downing of the MH17 over Ukrainian territory by the Russia-controlled illegal military units that killed 298 people, of which 38 were Australians. The increased interactions and dialogue that followed this tragedy accelerated the creation of a resident embassy of Australia in Ukraine later that same year.

The investigation of the tragedy together with Belgium, Malaysia, the Netherlands, and Ukraine – as well as holding Russia responsible for the attack as was concluded by an investigative team – for a long time became the cornerstone of Australia-Ukraine relations. The MH17 catastrophe demonstrated that nothing is too distant, and one cannot remain unconcerned only because something is happening far away and does not affect one directly – because, at one moment, it could.

In 2014, the Ukrainian President visited Australia for the first time, and for the first time the Australian Foreign Affairs Minister visited Ukraine. This was followed by more state visits of ministers and MPs on both sides in later years. For example, Stephen Parry, President of the Senate of Australia, visited Ukraine in 2017, and a Ukrainian delegation comprising the Minister for Defence, the Minister for Interior, and the Vice Prime Minister for European and Euro-Atlantic integration paid a visit to Australia in 2018. In 2018, a Ukrainian veterans team participated in the Invictus Games held in Sydney.

Shortly after the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukraine appointed the new Ambassador to Australia, Vasyl Myroshnychenko, who received and continues to receive rave reviews in Australia (Vasyl the Bushmaster’ is more arms dealer than ambassador, Ukrainian ambassador steals the show at Australian Defence Industry Awards ) and is famous for using all possible tools to mount support, for instance, including lobbying arms supplies through Eurovision stars.

In turn, Australia has taken a very active position in condemning the Russian aggression. In July 2023, Australian Prime Minister Antony Albanese said:

“Australia, of course, is a long way from Europe. But one of the things that this war has done is remind us that in today’s interconnected globalised world, an event such as the land war in Europe has an impact on the entire world. We’ve been impacted by our economy, [and] we’ve been shocked by the brutal invasion and the disregard for the international rules-based order, which we had come to think was something that we hoped would be a permanent presence. So, it is important that the democratic world react to defend the rules-based order”.

Australia’s unwavering support of Ukraine was evidenced through all resolutions in the UN General Assembly, the application of sanctions, and humanitarian and military support to Ukraine provided from the start of the invasion.

In 2022, Australia supplied to Ukraine as part of the humanitarian aid over 79,000 tons of coal, supporting Ukraine amid Russia’s strikes on Ukrainian energy entities. In late 2023, coal supplies remain one of the main topics for Ukraine-Australia cooperation, as the major Ukrainian NPP remains seized by the Russian Federation.

In March 2023, Australia imposed sanctions on 90 individuals and 40 entities of Russia, having stakes in Russia’s war, not to mention the provision of 90 Bushmasters and the commissioning of 70 service people to train Ukrainian soldiers in the UK.

As of June 2023, Australia is one of the largest non-NATO contributors to Ukraine. Since March 2023, Australia has been sending 100 so-called “card-board drones” to Ukraine monthly as part of another 30 million USD aid package, with the drones proving to be highly effective. In October 2023, Australian media published reports of transferring Slinger counter-drone systems to Ukraine. By December 14, 2023, it had committed 910 million AUD, of which 730 million AUD were for military support

(~616 million USD in total, and 494 million USD for military purposes). At the same time, Australia has declined, so far, the Ukrainian request to provide Hawkei armoured vehicles.

Additionally, in July 2023, Ukraine inquired about the condition of “dozens of F-18 fighter jets”. This question proved to be “complicated” for Australia, and the talks are still ongoing. As of December 2023, the Ukrainian government has continued to push talks about 41 Hornet F/A-18 fighter jets, of which 14 could be readied for transfer. Although the negotiations about the provision of fighter jets are tough, Australia has deployed to Germany its E-7A Wedgetail aircraft with up to 100 crew and support personnel for six months “to protect a vital gateway of international humanitarian and military assistance to Ukraine”.

Importantly, Australia also supports the legal action against Russia, having joined Ukraine’s application to the International Court of Justice challenging Russia’s claim to have invaded due to Ukraine having conducted genocide in its Eastern territories. Besides, Australia is among the countries that backed Ukraine’s suggestions to strip Russia of its UN Security Council veto powers, underscoring the need for UN SC reform and the constraints on using veto rights.

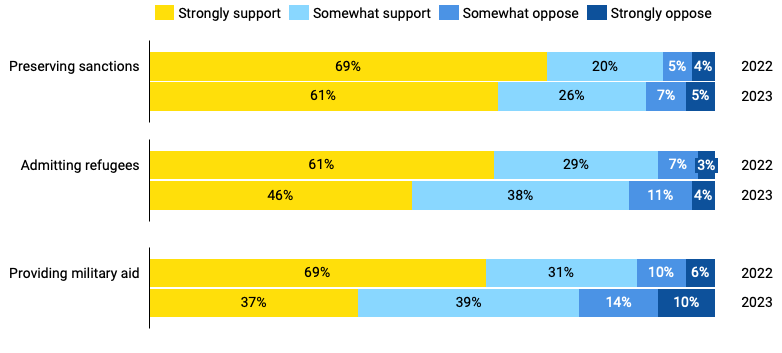

Australian population support remains high, although small signs of its decrease are also evident in the Lowy Institute Poll 2023.

Graph 1. Popular support of Ukraine in Australia, 2022-2023, %

Source: Lowy Institute

On December 9, 2023, Australia announced the appointment of the new Ambassador of Australia to Ukraine – Paul Lehman, with experience in Papua New Guinea, Nigeria, and Afghanistan, with his previous focus being Development and Governance. Although the new Ambassador does not seem to have recent experience in the Eastern European region, his background in countries that have recently experienced internal or external conflicts would be useful for his new position. His previous focus on governance and development suggests Australia would pay more attention to the structural reforms within Ukraine.

Australia helps Ukraine not only in terms of political, security, and economic cooperation. Following the start of Russia’s full-fledged aggression against Ukraine, Australia launched the Ukraine-Australia Research Fund, supporting short-term visits of Ukrainian scholars to Australia and giving access to Australian research facilities to Ukrainian scientists. Twenty-one grant recipients affected by the war were awarded 330,000 AUD (~223,000 USD).

Trade Relations

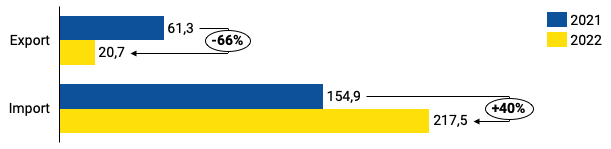

Talking about economic relations, Ukraine and Australia did not have a sufficiently developed trade for the first fifteen years of Ukraine’s independence. It started growing in 2008 and continued to grow until Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014. Recovering from the consequences of the 2014 annexation and occupation, the amount of trade started growing again. In 2021, according to the UN Comtrade Database, Ukraine’s exports to Australia constituted approximately USD 61.3 million, whereas imports from Australia constituted around USD 154.9 million, which was a substantial increase both for exports and imports as compared to 2020.

Graph 2. Exports to Australia and imports to Ukraine by year, million USD

Source: UN Comtrade Database

Recovering from the COVID drop in trade, in 2021, reportedly, the main export sectors for Ukraine to Australia were metallurgy and machinery, as well as fats and oils of both animal and vegetable origin. Whereas Ukraine mostly imported mineral fuels, machinery, pharmaceuticals, optical devices, wool, jewellery, paper, and cardboard.

Following the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, the trade relations changed significantly, with exports to Australia reaching USD 20.7 million and imports from Australia – USD 217.5 million. Due to the hostilities in Ukraine’s territory, the countries witnessed a sharp decline in exports and a certain upsurge in imports, attributable to the overall economic blow Ukraine received because of the invasion.

Graph 3. Exports to Australia and imports to Ukraine in 2021-2022, million USD

Source: UN Comtrade Database

Most metallurgy and machinery facilities are located either in the now-occupied territories or near the frontlines, where they were either damaged or needed relocation. However, the fall in exports probably would have been bigger unless Australia had introduced the cancellation of import duties. In the summer of 2023, the abolition of import duties was extended for an additional year.

Importantly, Ukraine sees economic cooperation as one of the priorities in its bilateral relations with Australia, as evident from Ukraine’s Ambassador’s comments at the Melbourne Chamber of Commerce saying that a free trade agreement with the EU creates access to one of the world’s largest markets for Australia and overreliance on China in terms of supplies and poses a strategic risk for Canberra.

Ukrainian diaspora in Australia

An important piece of the jigsaw of the Ukraine-Australia bilateral relations is the Ukrainian diaspora in Australia. Ukrainian immigration to Australia peaked after the end of World War II and the collapse of the Soviet Union. With over 46,000 thousand Ukrainians populating Australia in 2016, another 11,400 people received humanitarian visas as of January 2024. There has been a huge influx of Ukrainians to the country, and Australia has warmly welcomed them. Since the start of the invasion, they have been pretty vocal in their support of Ukraine, demanding the Australian government’s action.

The main organisation bonding all Ukrainians in Australia is the Australian Federation of the Ukrainian Organizations (AFUO), which unites 22 national community organizations with social, cultural, religious, educational, and other focuses. The member organisations include regional representations of Ukrainian communities from Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland, Australian Capital Territory, Southern Australia, Western Australia, and Tasmania. This means that Ukrainian communities are represented in all six Australian states and one of the internal territories. These territories together encompass close to 99% of the Australian population. This proves that the Ukrainian community is developed and vibrant, striving to help their home country even from afar.

The Ukrainian diaspora has been particularly active in the state of Victoria. It claims that the majority of people of Ukrainian descent live in Victoria and New South Wales. The Association of Ukrainians in Victoria unites scouting groups, cultural clubs, social clubs, and schooling groups. Virtually all Ukrainian communities across Australia organize cultural events, as well as humanitarian and military fundraisers for Ukraine and the Ukrainian refugees in Australia.

Among other AFUO member organizations are scouting, women, and youth organisations. There are also active catholic and autocephalous Christian eparchies. Cultural and educational organisations of Ukrainians are also active. Importantly, there is a functional Australian Ukrainian Chamber of Commerce, helping develop business ties and engage Australian businesses in investing in Ukraine and trading with it.

As experience shows, having an active diaspora is vital for developing relations with a country and maintaining its support. Thus, Ukrainians who settled in Australia, who are of Ukrainian descent, and who arrived in Australia after 2022 are important actors within the framework of bilateral relations between the two states.

The history of bilateral relations between Australia and Ukraine demonstrates an increased commitment on both sides and great potential for the relation development which will be addressed in more detail in the next chapter.

CURRENT SITUATION AND COOPERATION POTENTIAL

To see the prospects of Ukraine-Australia bilateral relation development, one needs to take a closer look at the situation both countries have found themselves in and the potential overlap in their interests. While the situation of Ukraine and its interest in gaining more support is clear-cut, it makes sense to dive deeper into why Australia needs to invest in this relationship. This chapter will focus on Australia’s political, economic, and security situations and challenges, as well as on possible opportunities for cooperation with Ukraine.

Current regional setup and challenges

Australia’s stance in the international arena is shaped to a large degree by its relations with Western countries and with the countries of the Indo-Pacific, which create over 60% of the global GDP. The governing doctrine for the country has long been “trade profitably with China while being securely protected by US military power”. As of 2015, some of the Australian political elites were talking about over-dependence on the US security-wise and were even sympathetic to Russia’s annexation of Crimea. It is doubtful that the sympathetic views of dictatorships persist after ten years of increased belligerence from both Russia and China, making the doctrine at least somewhat outdated. Together, Australia and Ukraine are Western and democratic countries standing for the same values, and their cooperation continues to unfold in this direction.

Faced with the North Korean nuclear threat, territorial disputes in the South China Sea, and the overall increased polarisation in the world, in the last few years, Australia has invested heavily in building its alliances, in particular, the AUKUS Treaty. On the one hand, this is evidence of the closer alignment with the Western allies – the US and the UK. On the other, the AUKUS Treaty famously put an end to a submarine production contract with France, thus creating an unnecessary rift between the democratic states, leading to France taking Australia out from the list of its strategic allies, which was later mended, though.

In general, the AUKUS Treaty, with its acquiring of nuclear submarines, serves as a sign of the growing concern over China’s position in the region, while also leaving Canada and New Zealand – the long-standing Five Eyes allies – out of the agreement, due to their lack of willingness to take a stronger stance on China.

Additionally, Australia’s political and security posture is formed by the Quad dialogue between Australia, Japan, India, and the US, and by the now partly obsolete ANZUS Treaty involving New Zealand and the US. The return to Quad dialogue in 2017 signals the growing importance of the Indo-Pacific and the renewed relevance of security arrangements in the region.

Australia has free trade agreements with a number of nations. For instance, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) allows Australia to enjoy FTAs with Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, New Zealand, Singapore, and Vietnam. Similarly, Australia has separate FTAs with China, Japan, the Republic of Korea, the UK, the US, etc.

Although politically speaking, Australia tries to keep its distance from China, economically, China still remains Australia’s major trading partner, both in terms of exports and imports, enjoying in 2023 a surge of 13% and 9% respectively, as compared to the last year. China accounts for approximately 30% of Australia’s exports and 21.4% of Australia’s imports.

Other top trading partners include Japan, India, Korea, Singapore, and the US, with total exports reaching USD 454 billion (AUD 686 billion) and imports – USD 349 billion (AUD 527 billion). Australia’s trade with Japan and the US has also grown remarkably – 24% and 20% respectively in terms of exports, and speaking about imports – 26% rise in trade with the US, and a staggering 103% in trade with Japan. This could signal, in part, the wish to enhance ties with the democratic allies and strengthen economic cooperation.

In 2022, Australia’s top export commodities were coal, iron ore, natural gas, education-related travel, gold, and petroleum. For imports, the main goods and services traded were refined petroleum, motor vehicles, freight transport services, personal travel, and telecom equipment.

Russia’s war against Ukraine and the sanctions subsequently imposed on the Russian Federation boosted prices for Australian thermal coal, driving high demand, for instance, from Europe and Japan. As a result, in 2021-2022, the coal export revenue increased by 73 bn AUD, about 186%, out of which between 21 billion and 39 billion could be directly attributed to Russia’s invasion.

Opportunities for Cooperation

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine serves as an impetus for Australia, on the one hand, to review its military capacities, bolster its defence efforts and production capabilities, and, on the other hand, regain its position in the world arena, including its reputation in the human rights sphere. It is an opportunity to learn from the experience of probably the largest conventional war since World War II.

Australia and Ukraine are far more interconnected than they might seem at first glance. The existing cooperation benefits both countries and makes each of them stronger – individually and collectively – in the international arena. There are clear steps that could be outlined in each sphere of cooperation: political, security, economic, social, etc. A valuable resource is the Ukrainian diaspora in Australia, which is willing to engage in promoting their respective country.

Ukraine’s experience in countering threats from a much stronger country could prove useful to Australia. Moreover, inadvertently, Russia’s aggressive war Ukraine is currently facing could serve as an impetus for Australia’s strengthening of its global political position and intensifying its trade with partners.

Considering the Chinese threat, it is hugely important to become more self-reliant both economically and from the point of view of security. For Australia, the regional configuration of powers is among the primary security concerns. In particular, rising China prompts Australia to strengthen its security alliances, as 75% of Australians believe China will likely pose a military threat to Australia in the next 20 years. Ukraine’s example can provide an invaluable lesson in diversifying supply chains and eliminating dependence on a particular market both in terms of exports and imports. Coal trade also might be a pertinent topic for future collaboration. Apart from that, gaining access to European Union markets through Ukraine could also potentially be an appealing opportunity. Through the Australia-Ukraine Chamber of Commerce, it is possible to deepen ties between the two countries’ businesses and facilitate trade development.

Additionally, since Australia is currently not producing a single missile, it is important to start looking into Ukraine’s experience of reinvigorating its industrial defence complex. Already existing cooperation between Ukraine and Australia in the military sphere could be enhanced through joint analysis of the use of provided arms. For instance, the cooperation could be built around the improvement of “cardboard drones”, given the experience of its real-life combat application and the modifications that Ukrainians had made to the provided weapons. This is just one of the examples, and it applices to almost all types of weapons sent to Ukraine. Australia could also explore opportunities for establishing joint military production facilities, given Ukraine’s experience and understanding of the most effective combat tactics. Ukraine’s progress in developing effective drones and organising their production is something that could prove a viable topic for military and scientific exchange.

Besides, Ukraine’s way of dealing with Russia, a powerful maritime state, without having limited navy capabilities is quite interesting to study. The use of maritime drones for intelligence and assault purposes might be of particular relevance for planning the mitigation of risks of possible confrontation with China. Lessons learned from the port blockades and navigation route disruption, both pre-war and during the war, are important spheres for Australia as a maritime state.

Undoubtedly, Ukraine has enormous experience in combatting cyber threats and disinformation, which could be of particular use to Australia, considering China’s belligerent way of using both cyber and information spaces. Australian professionals in relevant fields could be particularly interested in exchanging experience and learning lessons to counter the Chinese threat more effectively.

Peace Formula, introduced by President Zelenskyy in 2022, opens additional spheres for cooperation. For Australia, issues of nuclear security, energy security, protection of the environment, upholding the global rules-based order and the respect for territorial integrity might be especially pertinent. In line with it is the support in the creation of the special military tribunal against Russia for the crime of aggression and enhanced cooperation in the sphere of finding legal mechanisms to transfer USD 300 billion frozen Russian central bank assets to Ukraine. This could also help lay the path for transferring frozen assets of Australia-sanctioned companies and individuals in the amount of at least USD 45 million.

Following the establishment of the Ukraine-Australia Research Fund, it is possible to enhance research and development cooperation since Ukraine has an advanced human capital. Moreover, Australia can engage more profoundly in the reconstruction efforts in Ukraine. Although Australia signed the Lugano Declaration at the Ukraine Recovery Conference 2022, at the URC 2023 in London, it was represented only by the High Commissioner to the UK, with the Foreign Affairs Minister Penny Wong prioritising other commitments. Despite the limited engagement of Australia in the recovery efforts, Australian businessman Dr Andre Forrest committed USD 500 million to the Ukraine Development Fund at the URC 2023.

Bilateral relations between Ukraine and Australia are a vivid example of how countries might find something in common, even if it does not seem plausible. This report suggests that bilateral relations should be studied further and enhanced to effectively tackle contemporary issues of modern-day international politics.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Australia-Ukraine bilateral relations have a lot of potential considering the challenges of the modern world. There are several main recommendations in key categories that can be highlighted.

Political cooperation

- Collaborate on expanding the Australian sanctions regime against Russia, including preventing the circumvention of sanctions.

- Focus on supporting Ukraine’s efforts to create a special tribunal on the crime of aggression.

- Work on finding a joint solution to the issue of frozen Russian central bank assets aimed to be used as reparations in order to be able to use it with regard to Russia’s frozen assets in Australia.

Security cooperation

- Work on expanding the nomenclature of weapons supply to Ukraine, such as the Hornet fighter jets and the Hawkei armoured vehicles.

- Enhance cooperation in the cyber sphere through experience exchange.

- Explore non-conventional threats to national security to counteract them effectively.

- Explore opportunities for joint military production.

- Launch cooperation on maritime security, threats in the maritime domain, new technologies and navy cooperation for both military and civilian purposes.

Economic cooperation

- Extend cooperation on coal supplies to help Ukraine overcome Russian shelling of power plants and electricity grids.

- Strengthen business ties through Chambers of Commerce and promote the expansion of exports and imports in goods and services (e.g. real estate, manufacturing, winemaking and investing in vineyeards in Ukraine ).

- Support Ukraine’s EU accession through technical expertise, pushing the reform agenda and political advocacy to create wider global value chains.

- Facilitate Australia’s involvement in the recovery of Ukraine both on public and private levels through government support and encouraging access of Australian contractors to Ukraine’s recovery market.

Social cooperation

- Ensure sufficient support is available for Ukrainian refugees in Australia allowing them to integrate and contribute to the Australian economy while they stay within the continent.

- Maintain cooperation on humanitarian assistance to the population of Ukraine.

- Deepen scientific cooperation in order to drive joint scientific and academic ventures to advance common knowledge of humankind.

- Organise cultural exchanges to dive deeper into each other cultures and facilitate diversity.

- This list of recommendations is not exhaustive but indicative and could indeed be amended and updated.

The publication is prepared within the project within the framework of the “New Global Partnerships for Ukraine: Expert Diplomacy and Advocacy”. This publication was compiled with the support of the International Renaissance Foundation. Its content is the exclusive responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the International Renaissance Foundation.