Introduction

Historically, Ukraine and Russia have been close neighbouring states. Moreover, for the largest part of their histories, Ukraine has been dominated by Russia and its predecessors. Ukrainian attempts to withdraw from the sphere of Russian influence have been rejected by Russia. Furthermore, during the period of its greatest domination, Russia attempted to control Ukraine by exterminating its elites and political opponents. Russia further ensured loyalty through a mixture of intimidation, the Russification of Ukrainian lands, deliberately engineered close economic ties rooted in their Soviet legacy and shared religious values. The Ukrainian Orthodox Church is subordinated to the Moscow patriarchy in order to preserve Russian domination on the Ukrainian terrain.

Starting in 1654, Russian/Muscovite tsars began to extend their control steadily over Ukrainian territory, and from this point on Ukraine faced the challenges of Russification and the attempts of assimilation. Russia was successful in imposing an imperial narrative on Ukraine by using existing instruments of control including linguistic proximity and common religion.

The Russian language was promoted as superior to the Ukrainian language, which was associated with lower social status. Since the two languages are closely related and share many common traits (vocabulary and grammatical structures), mutual comprehensibility is relatively high. Many Ukrainians are native speakers in both Russian and Ukrainian, and have a lot of exposure to both languages, so bilingualism is prevalent in Ukraine.

During the 1920s, many of Ukraine’s spiritual leaders, artists and philosophers, who produced some of the nation’s greatest works, were either shot or sent to labour camps (gulags) where they would die of hypothermia and/or exhaustion. This loss of the Ukrainian elite was later called the “Shattered Renaissance» (a term proposed by the Polish publicist Jerzy Giedroyc). Moreover, the Great Famine of 1933 resulted in a further weakening of the Ukrainian nation and its elites. Loyalty to Russian elites was a matter of survival, and it had an impact on the further development of relations between Ukraine and Russia.

The effects of the termination of elites, the Russification and the construction of loyal attitudes through the use of terror and intimidation has created a strong ideological, economical, and political interdependence. As a result, both Russia and Ukraine share close cultural, ideological, and economic ties.

The established historical ties and loyalty towards Russia are so strong that, even in 1991 when Ukraine gained independence after the collapse of the Soviet Union, not that many things changed. Ukraine was a country intellectually decapitated, for which the effects of Russification and artificially constructed loyalty to Moscow (not to mention close economic ties with Russia) assured dependence. This could be further illustrated by the generally positive attitude of Ukrainians towards Russians. However, this started to deteriorate in 2012, and during the period of 2012 to 2015 the number of those holding very positive or positive opinions about Russians decreased from 80% to 30%. By 2017, only 34% had a positive attitude towards Russians.

The Russian minority population is another instrument of influence which allegedly accompanies the historical dominance of Ukraine. Russians are the second most numerous ethnic group in Ukraine. In 1989, they made up 26.6% of the population, a figure which had fallen 4.8 percentage points to 17.3% by 2001. Although 2001 was the last time a population census was conducted, polling data from 2017 show that Russians accounted for only 6.3% of the Ukrainian population in that year. Thus, the impact of this factor of influence is gradually decreasing.

If we consider religious proximity, the Russian Empire cooperated closely with the Orthodox Church, which was seen as important tool of legitimisation and stability. Today, Russia continues to follow this policy, using the Orthodox Church as an instrument of its politics of hegemony while supporting the institution’s aspirations. In Ukraine, this policy is facilitated by the fact that a majority of Ukrainian Orthodox believers declare themselves members of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church headed by the Patriarch of Moscow (there is also a Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Kyiv Patriarchate, which emerged in 1992 but remains unrecognised by canonical Eastern Orthodox).

Despite the victory of Viktor Yushchenko (often perceived as an anti-Russian politician) in the 2004 election, Ukrainian political elites abstained from organising anti-Russian media campaigns. Throughout this period (2004 to 2013), Ukrainians never held negative views of Russians, only turning against the Russian state and its leaders because of Vladimir Putin’s aggression.

Vulnerable groups

Based on the above proximities and consequent vulnerabilities, the Russian Federation is shaping narratives which have an impact on the population of Ukraine.

The Kremlin’s disinformation campaign targeting Ukraine uses a wide variety of techniques. It adapts its messages to different audiences, whether in eastern Ukraine or Western Europe. It not only brazenly seeds disinformation, but ensures that its lies are entertaining and emotionally engaging, and fits them into a strategic narrative tailored to match the preconceptions and biases of its audiences. In order to make this content appealing, Russia is prepared to fabricate stories entirely, using photos and video footage to suit Russia’s needs. A full range of media, from cinema to news, talk shows, print, and social media are engaged in promoting official Russian narratives.

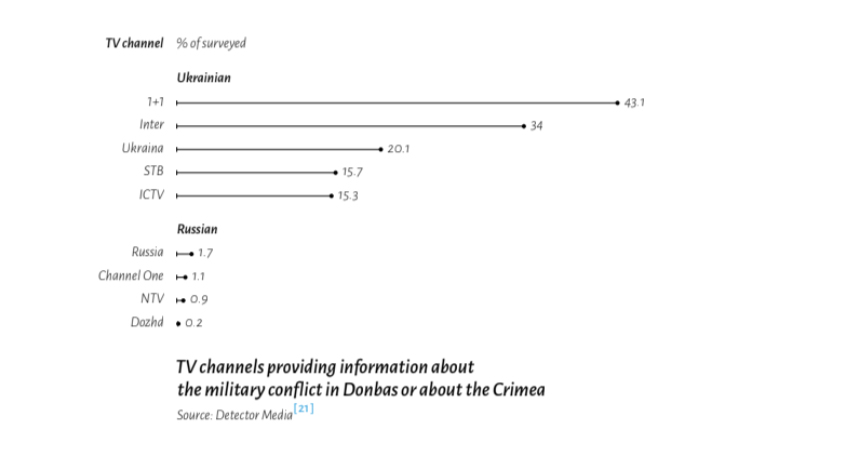

The Russian language and media are used as one of the channels of influence (in particular, the Russian-speaking population and Russian minorities in Ukraine). Russian media dominate in the eastern part of Ukraine, and are almost the exclusive source of information in the regions of Donetsk and Luhansk, neither of which are controlled by the Ukrainian government. However, according to data obtained by StopFake,disinformation is spread throughout Ukraine. A survey conducted by this organisation revealed that the main channels of Russian propaganda are Russian traditional media (identified by 45% of the respondents) and Russian Internet media (34.5%).

Allegedly, common religion is also a precondition for channelling propaganda. Conscious of the role played by Pope John Paul II in supporting the Solidarity movement in Poland, thereby contributing to the demise of the Soviet Union, the Russian leadership started using the same techniques to strengthen Russian imperial imperatives through the Russian Orthodox Church, which consists of 12 069 parishes.

A useful tool for defining vulnerable groups in Ukraine is the Index of the Efficiency of Russian Propaganda, released by Kyiv International Institute of Sociology in 2015. According to the results of this research, people over the age of 70 are slightly more vulnerable to Russian propaganda. People with a higher education are slightly more resilient to Russian propaganda. Education doesn’t play a key role due to a lack of media literacy skills and low demand for alternative sources of information (according to the data obtained by StopFake 58.4% of the respondents do not feel they need additional knowledge or skills to detect propaganda). However, key differences can be identified in geographic terms. The inhabitants of the western and central regions of Ukraine are the least vulnerable to Russian propaganda. The Index of the Efficiency of Russian Propaganda places vulnerability four times higher in southern and eastern Ukraine than in the western part of the country. The authors of the Index suggest that the main counter-propaganda efforts should be applied in the Odessa and Kharkiv regions.

Media landscape

The Ukrainian media landscape has been taking shape since the country gained independence in 1991. In the course of the initial privatisation process in the early 1990s, which was marred by corruption, a few oligarchs accumulated large amounts of capital by gaining control of the key industries of the country. As a result, the mainstream media outlets were obtained by the business elites who had privileged relations with the authorities.

At the same time, efforts to strengthen independent journalism in Ukraine were undertaken. Western donors including the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), National Endowment for Democracy, Internews, and the International Renaissance Foundation (Open Society Network) alongside the governments of the United Kingdom, Germany, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark supported independent media. Funding went to educational programmes for journalists, development of information legislation that meets democratic principles, journalistic projects, and support for investigations.

According to Freedom House, Ukraine was mostly evaluated as partially free in terms of freedom of speech, except for in 2003, 2004 and 2014, when the country was marked as not free. The lack of freedom of speech and the dependence of media on their owners, amongst other things, led to the media being used to foster political interests and agendas, with delays in reforming state-owned media, intimidation and attacks on journalists and impunity for the perpetrators. However, at the same time a new generation of journalists was gradually emerging.

In 2000, independent journalism in Ukraine experienced a major setback when Georgiy Gongadze, the founder of the opposition website Ukrayinska Pravda, was murdered. It was one of the most high-profile criminal cases and attacks on independent journalism in Ukraine. Gongadze criticised the authorities, investigated President Leonid Kuchma and the activities of his entourage. For these actions, journalist received phone threats. On September 16, 2000, he disappeared, and six months later his headless body was found in the forest near Kyiv. Indirectly, the tragedy led to the Orange Revolution of 2004. Only in 2013 was former senior police officer Oleksiy Pukach, the hired assassin who had killed the reporter, tried, convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. Pukach’s paymasters still haven’t been found.

The vulnerability of the information space in Ukraine was very high at the beginning of 2014 due to some inherited preconditions. First was the formidable dependence on foreign states and media corporations, the vast majority of which were of Russian origin. This primarily manifested in the appointment of Russians as top managers at Ukrainian channels. Also there was a dominance of Russian channels and media products on Ukrainian cable networks. Second, faced with only modest support for the domestic film industry, all national and regional TV channels were filled with Russian TV serials and films transmitting pro-Russian narratives. Third, the Ukrainian media market was characterised by excessive political pressure and a concentration of mainstream and regional media in the hands of oligarchs and businessmen close to Yanukovych. Public media was openly censored by the central and local authorities. In this environment, it is no wonder that Ukraine was forced to start building an information security system from scratch in the media space.

The start of Revolution of Dignity of 2013 to 2014 gave birth to conflict journalism in Ukraine. The journalists required new skills, such as fact-checking in extreme conditions, mastering the basics of safety and so on. By 2014, it was clear that Russia was waging a disinformation war against Ukraine, which included the Russian media’s one-sided coverage of events, distortion of facts, outright lies, etc. The realisation of these facts has impacted the development of Ukrainian journalism, for example through the launch of public broadcasting.

A recent poll from Internews Ukraine revealed a steady decline in the number of Ukrainians consuming Russian media (across all outlets) in Ukraine, a trend which has been continuing over the past three years. The levels of trust in Russian television in Ukraine fell from 20% in 2014 to just 4% in 2015. For online Russian media, it dropped from 16% in 2014 to 8% in 2016, and for print it fell from 8% to 2%. Trust in Russian radio also fell, from 8% to 3% within the same period. In 2017, only 1% of respondents said they consumed Russian media, compared to 4% the year before. One of the experts interviewed admitted:

‘The restriction of the Russian Federation’s influence on the information space of Ukraine had a positive effect. At least, it narrows the window of possibilities for Kremlin manipulators. Therefore, I personally and my organisation support the prohibition of Russian film products and the prohibition of Russian TV channels, as well as language quotas on radio and television’.

The Law on the System of Foreign Broadcasting of Ukraine kickstarted the creation of Ukrainian information content for foreign consumers. In October 2015, the Multimedia Broadcasting Platform of Ukraine was launched, incorporating the resources of the TV channel UA|TV and the National News Agency Ukrinform.

In 2017, Ukraine was ranked 102nd in the World Press Freedom Index. The situation had slightly improved compared to 2016, when Ukraine was ranked 107th.

According to an assessment by Freedom House, Ukraine in 2017 was defined as partly free. In this regard, Ukraine has made significant progress in comparison to 2013, when it was marked as not free. However, in recent years there has been some slow-down in the progress of reforms related to media freedom (but at the same time more attention is being paid to measures counteracting Russian propaganda and legislation, strategies and doctrines, alongside a special budget aimed at financing the respective measures).

Despite the mentioned positive developments there are still grounds for concern. In particular, with the start of the war in Donbas, Russian project leaders had to rethink their policies and began faking objective journalism, instead of pushing straightforward and crude propaganda. Projects do use the services of some genuinely pro-Ukrainian journalists, who do their work to high professional standards, but in general they on the 80/20 Pareto principle, providing 80% of neutral information and 20% of Russian propaganda. Among websites transmitting Russian narratives, InfromNapalm names Vesti, UBR, and Strana.UA. According to Ukrainian Internet Association data, in December of 2017 these resources had the following Internet audience: Strana.UA – 12% (ranking ninth in the top 100 Ukrainian news websites), Vesti – 8%, UBR – 4%. Research on propaganda in the Eastern Partnership countries adds the TV channel Inter, one of the most popular in the country, to this list. The National Council of Television and Radio Broadcasting of Ukraine ranks Inter sixth among the most viewed TV stations.

Legal regulation

Following the annexation of Crimea in 2014, work aimed at creating specific information security documents was launched. In April 2014, the National Security and Defence Council (NSDCU) adopted measures to improve the development of state policy for the information security of Ukraine. It tasked Ukrainian government and state institutions with drafting some legal and conceptual documents: the Strategy for The Development of the Information Space in Ukraine, the Informational Security Doctrine, the Strategy for Cybersecurity in Ukraine, and to draft laws on Cybersecurity in Ukraine. The decision also sought to find legal solutions to counter information aggression by foreign states, by virtue of banning selected foreign television channels from broadcasting in Ukraine or creating special accreditation and protection regimes for journalists.

Since 2014, the Ukrainian authorities have adopted a number of reforms, including media ownership transparency and access to state-held information. The Law on Transparency of Media Ownership was adopted on September 3, 2015, establishing one of the best legal frameworks in Europe. Although the legislation is in place, it is often implemented poorly. Transparency in the media sector should be improved. One expert interviewed for this study said:

‘The main threat in information security area is an oligarch controlled media market. In Ukrainian realities, this often turns into censorship by the owners’.

The State Committee for Television and Radio Broadcasting of Ukraine has been assigned to lead work on developing the Strategy for the Development of the Information Space and the Information Security Doctrine. In September 2014, the State Committee presented the draft Strategy for public discussion. Although the document was prepared following the decision of the National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine to react to Russian information aggression, the Strategy was met with numerous concerns from civil society and independent media experts. The core concern was that the draft Strategy greatly echoed the Strategy for Information Society development adopted in 2013.

In 2015, with the establishment of the Ministry of Information Policy, the coordination centre has shifted towards this new institution. A special expert council has been established under the ministry, tasked with the creation of a new draft of the Information Security Concept. Despite international support and the inclusive and transparent process of drafting, the Concept did not become law. But, at the same time, the ministry took up the baton of development of the Information Security Doctrine.

The first stage in securing Ukraine’s media space was of a restrictive nature. Since 2017, the National Council of Television and Radio Broadcasting of Ukraine has restricted the broadcast of 77 Russian TV Channels on cable networks in Ukraine. It is important to bear in mind that, as of 2014, there were 82 Russian cable TV channels in Ukraine. The Ukrainian State Film Agency, in accordance with the norms of the Law of Ukraine on Cinematography, cancelled the state registration of films produced in Russia and released after January 1, 2014.

In November 2016, the Law on Amendments to the Law of Ukraine on Television and Radio Broadcasting initiated a gradual introduction of quotas for songs and programmes in the Ukrainian language in radio broadcasts. In October 2017, the Law of Ukraine on Amendments to some Laws of Ukraine Regarding the Language of Audiovisual (Electronic) Mass Media established that transmissions, films and news in Ukrainian must account at least for 75% of the total length of the programmes and films. According to the law, local broadcasters must have at least 50% of programming in Ukrainian.

In April 2017, the National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine (NSDCU) added Russian legal entities Yandex, Mail.RU Ukraine, VKontakte, Odnoklassniki, and others to the sanctions list. The decision of the NSDCU was enacted by Presidential Decree in May 2017. According to the Ministry of Information Policy of Ukraine, this led to a drop in the number of VKontakte users, from nine million to 300 000, which proves that Ukrainians support the decision.

In 2017, the president of Ukraine signed legislation on the Cybersecurity Strategy of Ukraine, after a number of severe cyberattacks on the telecommunication systems of state institutions and entities of critical infrastructure. In this domain, legal efforts were advanced with the adoption of the Law of Ukraine on Cybersecurity in Ukraine in September 2017.

In February 2017, the new Information Security Doctrine of Ukraine was adopted. It defines the national interests of Ukraine in the information sphere, the threats to their implementation, and the directions and priorities of the state policy in the information sphere. However, despite its progressiveness and relevance, this document has not yet formed the basis for the development of an integral normative system of building information security. Many respondents from Ukrainian state institutions confirmed that they did not take this document into account while planning their activity in information security area.

In June 2017, the government approved the first Action Plan on the implementation of the Concept of the Popularisation of Ukraine in the world and of promoting the interests of Ukraine in the global information space. The document was prepared by the Ministry of Information Policy and envisages very deep inter-agency cooperation.

In this vein, one should also mention the Public Diplomacy Strategy, which the MFA is still in the process of creating.

In 2017, the Strategies of Information Reintegration of Donbas and Crimea were prepared, and the implementation process started. The documents are aimed at the creation of preconditions for the reintegration of Crimea and inclusion of the temporarily occupied territories of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts into the Ukrainian informational space and the promotion of pro-Ukrainian narratives, and envisages institutional and organisational steps.

Institutional Setup

The Information Security Doctrine (ISD), adopted in February 2017, proposes an enhanced institutional mechanism:

- The National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine

- The Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine

- The Ministry of Information Policy

- The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine

- The Ministry of Defence of Ukraine

- The Ministry of Culture of Ukraine

- The Ukrainian State Film Agency

- The National Council of Television and Radio Broadcasting of Ukraine

- The State Committee for Television and Radio Broadcasting of Ukraine

- The Security Service of Ukraine

- Intelligence Services of Ukraine

- The National Institute for Strategic Studies

- The State Service of Special Communications and Information Protection of Ukraine

The document also acknowledges that the implementation of the Doctrine is possible only with the proper coordination of efforts by all state institutions.

Key measures and activities in accordance with the provisions of the Doctrine will be determined by the National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine. In April 2017, the Service for Information Security was established within the new structure of the Staff of the NSDCU.

It would be appropriate to mention here the Committee on the Freedom of Speech and Information Policy of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraineas a part of the institutional framework in the information security domain. This parliamentary body is in charge of preparing and overseeing all draft laws in the information policy and security domain.

On an executive level, one has to include the press services of ministries and regional state administrations in the framework. Although absent in the ISD, they are mentioned, along with the parliamentary committee, in the system of public institutions in field of the information policy indicated in the MIP reports and action plans.

A significant part of information security coordination and implementation was taken over by the Ministry of Information Policy, established in January 2015. The ministry, for the moment, is the main body in the system of the central institutions of executive power, which forms and implements public policy in the areas of media development and information security. As of 2016, the ministry had formed four strategic directions for the development of information policy:

- Development of the information space of Ukraine;

- Public StratCom system development;

- Information reintegration: annexed Crimea, temporarily uncontrolled territories of the Luhansk and Donetsk regions, internally displaced persons;

- Popularisation of Ukraine and its values in the world.

As many experts confirmed, the existence of the ISD and clear indication of the institutional framework has not contributed drastically to the effectiveness of the implementation of information security policy. As one expert put it during an interview:

‘There are some significant steps towards improvement. This is primarily the Information Security Doctrine, which covers information interests. This is very important because it is the basis, but now we have to look at the division of powers in public authorities. This mechanism, which is prescribed in the Information Security Doctrine, and, in fact, is well-written, should be implemented. However, there are problems with implementation because, if we look at the list of powers, we come to chaos. And I think this chaos in the division of powers in the area of information security is the main regulatory barrier’.

The first and most serious problem is that no functions audit was conducted prior to the elaboration and adoption of the ISD in the realm of information security. Functions sometimes overlap, and there are sometimes gaps in information security performance. As one of those interviewed described it:

‘The doctrine is an important thing for those who made it and for the main executor. It seems to me that this doctrine lacks the involvement of other authorities. Even for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, this is not what we use every day. It is not a reference point. I consider this to be the main problem of this document’.

There exists a traditional level of interaction between the state ministries and agencies, as well as with some NGOs, on information security and media issues, but this interaction does not extend to the utilisation and building of an all-encompassing and comprehensive system of monitoring and reaction to information security challenges.

However, some positive developments took place in 2017 after the adoption of the ISD, and these might be considered as progress in implementation in terms of strategic vision and coordination of efforts.

In July 2017, a project team was formed within the framework of the creation of the system of state strategic communications, which included representatives of the MIP, the NSDCU, the National Institute for Strategic Studies and NGO StratCom Ukraine. During meetings in July and August 2017, the overall design of the project was determined and a detailed project plan was developed.

In 2017, the Ministry of Information Policy also created an inter-agency commission for popularising Ukraine in the world, including representatives from ministries, businesses, NGOs and PR specialists. From the outset, the Commission has been tasked with creating the official brand of Ukraine and taking stock of all the initiatives of this kind done by government bodies and business.

In terms of cooperation with NGOs and civic initiatives, one of the experts said:

‘Such cooperation exists, but it lacks cohesion and communication channels between civil society and state authorities. On the other hand, one should realise that the state authorities may not always allow themselves to stick to all the proposals offered by of the public. Let us not forget that democracy does not mean unanimity, but democracy is a precondition for national interests and ways of implementing them. They may be different, but they must at least be somehow agreed’.

Many experts from NGOs mention a good level of cooperation, although this is highly dependent on their specific project activity.

Kulakov, a project director for Internews Ukraine, said:

‘Systemic cooperation starts with projects. For instance, there was a project on freedom on the Internet. A task force was established. We cooperated with the Security Service of Ukraine, Ministry of Defence, Ministry of Information Policy and the Internet Association. In other words, it is systemic cooperation. However, when a project finishes contacts are there but cooperation becomes sporadic, which is often the case for the third sector’.

Civic activists also mention the cooperation platforms created by the MIP and MFA (Expert Council and Public Council under the MIP and Public Council under the MFA).

In Focus

Russian singer Samoilova banned from attending the 2017 Eurovision Song Contest in Ukraine

This is a positive example of the coordination of efforts between different Ukrainian public authorities to protect the information space. In March 2017, on the eve of the Eurovision Song Contest in Kyiv, the Security Service of Ukraine issued a travel ban on Yulia Samoilova, a Russian singer with disabilities, who was supposed to take part in the contest. The argument was clear and legitimate from the Ukrainian side. Samoilova had previously taken part in a concert in Crimea after its annexation, crossing the Ukrainian state border outside Ukrainian checkpoints, which is prohibited by Ukrainian legislation. The Kremlin’s aim was to discredit Ukraine by portraying it as immoral and ineffective. The Samoilova case was one in a series that the Kremlin applied in this disinformation campaign. But, due to the well-thought approach to the communication side of the decision, Ukraine succeeded in creating the truthful image.

Digital debunking teams

Debunking teams have been serving a crucial role in fighting Kremlin-led propaganda since the start of aggression against Ukraine. Many of these groups appeared spontaneously as a reaction the Kremlin-backed disinformation campaign surrounding the annexation of Crimea in February and March 2014. Due to the unpreparedness of the Ukrainian state authorities, volunteer and civil society groups performed a lot of activity in this realm. Even now, the ISD acknowledges the importance of civil society involvement in countering Russian disinformation.

There are different types of the initiatives on the ground taking into account the diversity of tools applied by Russia in its disinformation war. They comprise fact-checking teams, open source intelligence communities, investigative journalism groups, media hubs, and expert networking agencies, social media initiatives, cyberactivists, and IT companies with specialised software.

The first initiative to mention is the project StopFake, established by Kyiv Mohyla Academy lecturers and researchers in March 2014. The website of the project initially focused on debunking Russian propaganda about events in Ukraine. As time passed, it evolved into an information hub where the team studied all aspects of Kremlin propaganda. StopFake’s information products are translated into 10 foreign languages to increase outreach. The initiative states its independent status and non-affiliation with any Ukrainian institution.

Information Resistance started as a non-government project in March 2014. It aims to counteract external threats to the informational space of Ukraine in the main areas of the military, economic, and energy sectors, and in the sphere of information security. Information Resistance functions as an initiative of the NGO Centre for Military and Political Studies. It is operated by Ukrainian reserve officers and is widely known for thorough fact-checking of the news and some inside military information delivered from the occupied territories of Ukraine.

InformNapalm is a volunteer community that was also launched in March 2014. Its main task is debunking disinformation provided by Russia. The international team is made up of more than 30 people from 10-plus countries. It focuses on fact-checking and investigative journalism connected to aggression and its impact on Ukrainians. Due to close work with other institutions from the information security realm, InformNapalm provides debunking with in-depth analysis and detailed reliable information in more than 20 languages. It has also issued a handbook of Russian aggression in Ukraine, called ‘Donbas in Flames. Guide to the Conflict Zone’.

Almost at the same time, in March 2014, the Ukraine Crisis Media Centre (UCMC) was founded by a group of media experts and civic activists to enhance Ukraine’s potential for resistance in the information space. UCMC is widely known for its press centre, which allows Ukrainian and foreign experts, politicians, and representatives of the civic sector to use this platform to inform domestic and external audiences about events in Ukraine. This often helped the Ministry of Defence and General Staff press services to deliver regular briefings and updates about the situation in the Anti-Terrorist Operation (ATO) zone.

Dating from 2014, Euromaidan Press (EP) is an online English-language independent media platform that focuses on events in and around Ukraine and provides translations of Ukrainian news, expert analysis and independent research. Its main tasks are to extend Ukrainian outreach abroad, and to promote non-partisan, non-biased information in the fight against the Kremlin-led disinformation campaign. Many of its news stories are devoted to the Ukrainian military fighting against Russia and its proxies in Donbas.

UkraineWorld is an overarching initiative proposed by Internews Ukraine in 2014 to bring together key Ukrainian and international experts and journalists interested in Ukraine, and to counteract Russian propaganda and disinformation. It functions as a communication network, mainly through the exchange of information. The website accumulates texts and analysis produced as a result of group discussions and debates.

Project Verify was launched by Internews Ukraine with the support of the Latvian Journalists Association in 2016. It is a verification assistant based on open data and online tools. It helps media users to draw their own conclusions about content needing to be verified.

The educational project LIKБЕЗ. Historical Front unites professional historians. The project community runs awareness-raising campaigns and debunking projects connected to historical narratives used by Russia. More than 50 Ukrainian historians have taken part in the project.

Some volunteer initiatives existed only for a short time in 2014, and aimed specifically to counter Russian propaganda. From March until May 2014, there was a special initiative launched by Ukrainian experts. A project called Ukrainian Information Front was devoted to establishing contacts with foreign media, mainly in the post-Soviet space, and delivering analysis and comments about the situation in Crimea and domestic politics in Ukraine. Although active for only a short period of time, the project united about 20 well-known Ukrainian experts from a wide array of policy areas. Contacts made by these experts with foreign media have been often used for delivering comments since then.

Since 2017, Western Information Front has been engaged in countering Russian information aggression and protecting good relations between Ukraine and its neighbours (Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, and Romania) from Russian provocations and disinformation .

Additionally, we have to mention some social media communities which are very visible in fact-checking and debunking activities. A group of volunteers named Group #IPSO #Trollbusters started its activity on Facebook by revealing the botnets used by the Kremlin, and the tactics and methods of their activity in social networks, at the end of 2014. In their posts, they also described changes in the narratives Russia used in its disinformation campaigns.

Similar to the previous group’s activity the volunteer initiative TrolleyBust has been engaged in detecting bots malicious accounts in social networks, and trying to ban them since 2014. In 2015, the initiative launched a special web service to detect and block Internet trolls and other sources of anti-Ukrainian propaganda. The aim is to give volunteers access to the toolkit and unite their efforts to clear the information space of propaganda oriented against Ukraine and Ukrainians. There are three main areas of focus for the ban: propagandists and pseudo-experts, bots and fake accounts, and other users that doubt the territorial integrity of Ukraine.

In 2014, the Boycott Russia Today FB community was launched. As well as calling for U.S. citizens to boycott RT, and urging U.S. cable and satellite TV providers to suspend RT from their channel line-ups, they regularly post myth-busting materials.

In 2015, under the umbrella of the Ministry of Information Policy, the Information Forces of Ukraine started. The aim of this Internet project was to mobilise users of social networks to counter Russian propaganda and extend the outreach of reliable information. Since August 2017, the project has officially been independent.

The initiative Ukrainian Cyber Forces is a network of Ukrainian IT specialists operating in cyberspace to block the bank accounts of terrorists and web pages with Russian propaganda. They are also active in investigating and reporting on the presence of Russian military personnel and equipment on Ukrainian territory. By the end of December 2017, they had blocked more than 200 websites belonging to Russians and separatists, as well as hundreds of web pages and blogs that published the personal data of Ukrainian servicemen.

Yet another very efficient group, Ukrainian Cyber Alliance (UCA), unites cyberactivists from different cities in Ukraine and all over the world. Since 2016, the group has performed a number of successful hacks on separatist web resources, personal emails and profiles. A recent famous flashmob campaign, #FuckResponsibleDisclosure, was launched at the end of 2017. Together with other IT specialists, the UCA has searched for vulnerabilities within government telecommunication systems, public web accounts and sites.

The Monitoring project OKO has been created by Ukraine’s Image Agency and Together for Ukraine, both of which are NGOs. The project consists of monitoring software based on Google and Bing which sorts articles about Ukraine by language, date, and popularity in foreign media and on Facebook. A specific algorithm automatically processes selected articles by content and its emotional coverage, as well as by frequency of mentions.

In Focus

MH17

Most of the interviewed experts emphasised that the Ukrainian response to the MH17 catastrophe was a good example of effective and efficient cooperation between government structures, security bodies, NGOs, think tanks, and journalists, which enabled proper, transparent, and open coverage of the catastrophe circumstances that if not prevented then at least minimised the damage from Russian propaganda and Russian attempts to blame Ukraine for shooting down the Malaysian Airlines Boeing. The patterns of cooperation and interaction applied then should be studied and further applied.

False suggestion of Ukrainian involvement in North Korea’s missile program

In August 2017, this article appeared in the New York Times. It showed that North Korea’s ICBM success had been made possible by illegal purchases of rocket engines probably from Ukraine. Although the material was based on a study by Michael Elleman, of the International Institute for Strategic Studies, Ukraine had many reasons to suspect Russian involvement in the story. This case is reminiscent of the Koltchuga scandal (the Ukrainian Passive Early Warning Radar allegedly sold to Iraq), which had farreaching image losses for Ukraine.

Regardless the origin of the fake news, Ukraine reacted in a timely manner and with high level of coordination of messages intended for external audiences.

As one of our experts pointed out:

‘It is very good that officials dealing with this issue decided to involve Volodymyr Gorbulin to debunk this fake news. He enjoys a high level of trust and he knows perfectly well all the technical details to dispel it’.

Media literacy projects

There are different kinds of media literacy programmes on the government (involving universities and schools) and civil society (educating broad population) levels.

In 2014 to 2017, media education and literacy projects gained some prominence and attention in Ukraine. However, from the outset, one should mention here previous media literacy activity provided by the Academy of Ukrainian Press and Telekritika (now Detector Media). The web portal Media Sapiens was launched by a Telekritika team in 2010, some time before the Revolution of Dignity. The aim was to enhance the media literacy of the audience, form critical thinking towards media and detect manipulative attempts to impact public opinion. Since then it has become a hub of information about media development, information security, media education, and literacy.

The primary goal of the Academy of Ukrainian Press (AUP) primary goal is the implementation of media education through the creation and encouragement of a leading media teachers’ network, applying international experience to help implement media education in Ukraine. The AUP focuses on the preparation of handbooks for teachers and the design of academic courses. Since 2013, it has been running the project ‘Media education and media literacy’, within the framework of which an online platform was launched in 2013. The platform was designed to facilitate the exchange of opinions between media teachers who promote transparency and publicity in the media educational environment. In 2016, the Road Map for Media Education and Media Literacy was introduced by the expert group of the AUP. This states that, at the moment, media education and media literacy are taught in Ukrainian secondary schools in the form of separate subjects (‘Basics of media literacy, ‘Stairway to media literacy’, ‘Media culture’, ‘Media education’, etc.), as well as integrated lessons. Media education and media literacy as a separate subject is taught in about 300 secondary schools.

In 2016, the National Academy of Pedagogical Sciences of Ukraine approved a new version of the Concept for the Implementation of Media Education in Ukraine. The previous version of the Concept dated back to 2010. The main goal of media education is to create the foundation for state information security, develop civil society, counter external information aggression, prepare children and youths for the secure and effective use of modern media, and form media literacy and media culture. In 2017, the Ministry of Education and Science approved a experiment on media education for 2017 to 2022, entitled ‘Standardisation of the cross-cutting socio-psychological model of mass media education implementation in Ukrainian pedagogical practice’. The experiment involves the implementation of media education in educational institutions, including nurseries, schools and higher education entities (153 institutions).

The OSINT Academy, a joint project of the Institute of Post-information Society and the Ministry of Information Policy was launched in 2015. A special online course is devoted to enhancing skills when working with open sources intelligence and searching for reliable data to fact-check. It also aims to increase public awareness of information manipulation, and to promote media literacy.

In 2016, Detector Media launched a multimedia online textbook for youths, detailing how to use media in day-to-day life and develop critical thinking towards media products. Another project, ‘News literacy’, is a course of lectures that aims to disseminate media literacy among the population in situations of conflict.

There is an interesting online game called ‘Mission of media literacy’, and a distance learning course called ‘Media literacy for citizens’, created as a joint initiative between IREX, AUP and StopFake. The curriculum of the distance learning course and the online game are based on materials from the media literacy handbook, which was created as a result of cooperation between the three organisations involved in the ‘Media Literacy for Citizens Programme’ , which was implemented in July 2015 and ran until March 2016. As part of the project, training seminars took place in 14 regions of Ukraine, primarily in the east and south. In total, more than 14 000 citizens took part in these training seminars.

Conclusions

Since the start of Russian aggression in 2014, the Ukrainian authorities and civil society have done significant work in order to build up national resilience in many areas, including in the information domain. One could hardly call the years 2014 to 2015 a successful period in terms of governmental strategic vision or institutional capacity. Some of the positive results should be attributed to volunteer initiatives and restrictions on media outlets promoting Russian propaganda.

It is fair to say that, from 2016 to 2017, the activity of Ukrainian public institutions intensified, as did cooperation with civic initiatives. Strategic planning and coordination became more visible. The Ministry of Information Policy more actively steers the implementation of information security policy. However, there is still room for improvement on all levels of public policy development and execution.

Ukrainian resilience to Russian disinformation is very multi-layered. First, both at state and societal levels, we are conscious that Kremlin-backed disinformation and propaganda as physiological operations (PSYOPS) are part and parcel of hybrid warfare, along with military aggression, trade and energy wars, annexation and occupation, and political destabilisation. Experiencing all these facets at the same time leaves the Ukrainian authorities with no illusions about the gravity of the consequences, or what is at stake. Second, since Ukraine has been placed at the core of the Russian global disinformation strategy, the state differs in the breadth and scope of the areas in which it must resist aggression. That said, in Ukraine there are three main directions in which it is necessary to apply different strategies and instruments to defend Ukrainian national interests. Both state bodies and expert communities have to deliver on information security tasks (1) on the sovereign territory of Ukraine, (2) in the occupied and annexed areas, and, last but not the least, (3) outside Ukraine. All three areas are crucial, but are very different in terms of narratives, channels and strategic tactics applied by the aggressor against Ukraine.

These two above mentioned arguments are very significant when it comes to comparative assessment of disinformation resilience in the wider CEE region. In quantitative and qualitative terms, the level of disinformation challenges and threats is far higher for Ukraine than for its neighbours. As a result, the number of tasks Ukraine needs to accomplish differs significantly from its neighbours. The number of tasks may partially explain why some of our interviewed experts sometimes feel pessimistic about the steps which have already been taken by the Ukrainian state. While other states have achieved success in countering disinformation using such methods, these alone are not enough in the case of Ukraine. This is especially true when experts refer to cooperation between state institutions, civil society, and the expert community.

As one interviewed expert concluded:

‘There are certain systemic problems, which stand in the way of cooperation, when political decisions are made based on the current context and political will. When this is done, little room is left for understanding the real state of the problem, for real reflections on the purpose, means, and possible consequences of state policy. In fact, there is no time left for what think tanks are doing’.

Recommendations

- 1. While the adoption of the ISD might be considered as a breakthrough in development in information security, it does not by itself create the necessary framework for public institutions and other non-government players to achieve the previously identified goals. More work has to be done to bring the necessary strategic documents to individual departments. However, this work should not be scaled down to a purely bureaucratic process. Even if not done in line with strategic planning, the implementation of IDS should be broken down on an operational level, and a clear hierarchical structure of documentation should be developed (information security strategy, information security program, information security short-term and mid-term action plans).

- 2. In 2017, the Ministry of Information Policy took a more prominent leading role. However, not all state bodies, NGOs, and journalists have recognised this, and therefore policy implementation is still fragmented. Further work is needed to establish a coordinated and coherent strategy. A case in point is strategic communication (stratcom) inside and outside Ukraine. Since the MIP is involved in government stratcom development, it should take the lead in the creation of an intrastate network of stratcom players, including those from the non-government sector.

- 3. The MFA is currently preparing the Public Diplomacy Strategy and is in charge of the coordination of external communication activity. Thus, it should be the responsibility of the MFA to map Ukrainian NGOs and think tanks to establish the potential for increasing outreach overseas and synchronising debunking and anti-propaganda efforts ‘to ensure proper synchronisation of communicators’, as stated by one expert. Further coordination might be provided under the plan of action on the implementation of the Concept of the popularisation of Ukraine in the world and of promoting the interests of Ukraine within the global information space.

- 4. Among the recommendations one should mention the necessity of embedding media literacy elements at all levels of primary, secondary and higher education. Every level of education has to be supplemented with adjusted programmes and interactive products oriented towards enhancing skills of responsible media consumption.

- 5. In the Ukrainian media, there is a deficit of personnel who are able to recognise propaganda and fake news professionally, not to mention a lack of professionals in the field of strategic communications. These factors weaken the media sector and make it vulnerable to foreign interference. Additional investment is needed in educational programmes (fact-checking, OSINT courses and Internet security) to strengthen media literacy, and to give new impetus to coordination between professional unions and groups, and cooperation between NGOs. Regular meetings are needed between the authorities and media in order to develop the habit of using unified terminology in fighting disinformation. The educational programmes should be both short-term and long-term. The short-term educational programmes should have the media community as the target audience whereas the long-term initiatives should be oriented towards pupils and students, with the aim of increasing media literacy in general.

- 6. Apart from the media, the situation in law enforcement should be tackled. Representatives of the police, the Security Service of Ukraine and other relevant government bodies should also be properly trained to be able to counteract propaganda, fake news, and disinformation campaigns. In this regard, cooperation with European and NATO structures working in the field of strategic communications will be of added value. The existing road maps of cooperation have to be enriched with new initiatives in the area. Moreover, improving skills in preventing cyberattacks and responding to them adequately and efficiently is essential for the representatives from all security bodies, not only the ‘cyberpolice’.

- 7. Another field in which the efforts should be applied is preventing the dissemination of fake news about Ukraine in foreign media. This can be done by encouraging the opening of contact points or branches for foreign media, which can learn from local experts. These measures would mean that foreign audiences would be able to get first-hand information about developments in Ukraine and reduce the likelihood of manipulation, fake news, and disinformation being spread. If such contact points are a medium-term goal, the state should immediately encourage the organisation of media tours to Ukraine for foreign journalists.