Underlining its neutrality the country failed to build strong enough army and failed to achieve the withdrawal of Russian troops from its sovereign territory. The level of penetration of Russian influence to the Moldovan political elites is also extremely high. Although nowadays the country is being ruled by the pro-European President and Government the positions of both are weakened by the economic turbulence and dependence on Russian supplies of gas. Moscow also supports separatist regime in Transnistria and propels secessionist moods in the autonomous region of Gagauzia. The recent steps of the Moldovan government aimed at deterring Russian dominance in the information sphere (e.g. banning the broadcasting of Russian propagandist TV-channels) and the attempts to investigate the Russian meddling into the political life of the Republic of Moldova may eventually have positive results and certainly deserve for the support of the EU and other international partners of Moldova to be successful.

Authors:

- Sergiy Gerasymchuk, Neighbourhood and Regional Initiatives Program Director, Foreign Policy Council “Ukrainian Prism”,

- Hanna Shelest, Security Studies Program Director, Foreign Policy Council “Ukrainian Prism”

Peer-review:

- Natalia Stercul, Foreign Policy Association of Moldova

Editor:

- Hanna Shelest, Security Studies Program Director, Foreign Policy Council “Ukrainian Prism”

Contents

- Moldova’s Hard Security Vulnerabilities

- Vulnerability of the Political Elites

- Economic Vulnerability

- Informational vulnerability

- Successful Cases of Discovering and Deterring Russian Influence

- The analysis of the probability of Russian reflexive control operations

- Recommendations on resilience, and managing vulnerabilities in the areas sensitive to Russian malign influence

Moldova’s Hard Security Vulnerabilities

Moldova, as a neutral state, which faces an irredentist conflict and still bears a Russian military presence on its territory, has a substantial level of hard security vulnerabilities that should be analysed, especially in the context of the Russian aggression against Ukraine, which actualised many of them. According to the 1994 Constitution of Moldova, a neutral state has been announced (article 11), emphasizing that the Republic of Moldova does not allow the deployment of foreign military in its territory. Nevertheless, the Transnistrian conflict and the remaining of Russian forces in its territory have undermined this posing. The status of neutrality had both positive and negative consequences for the country. On the one hand, it has prevented hostilities renewal and partially decreased Russian military pressure. On the other hand, it resulted in neglected Armed Forces and military capabilities when security sector development paid attention mostly to police and domestic security services.

In 2011, the latest version of the National Security Strategy of Moldova was adopted. The main threats named there tended to prioritise soft security: poverty, economic underdevelopment, energy dependency, criminality, corruption, demographic problems and migration, population health, environmental pollution, man-made accidents, low information security, and unstable banking and financial sector. Transnistrian conflict, tensions and foreign presence in the area (not naming it is only Russian presence), external pressure were also named but without proper articulation. The Russian Federation policy was not named among the threats, and the country was mentioned in the context of strategic partnership development together with the USA, the EU, Ukraine, and Romania.

In 2016, a new version of the Strategy was drafted, where information security and energy dependency were upscaled, moreover, Russian attention to the region was not named positively. Due to this fact, the newly elected pro-Russian President Dodon recalled the document from the Parliament in 2017, and it has never been adopted. In June 2022, it was announced that the new Strategy should have been presented in autumn, so to reflect the changing security environment. The release of the Strategy was delayed though.

Another document defining threats to national security was adopted in July 2018 – the National Defence Strategy of Moldova. The neutral status of the state was reaffirmed as crucial, while integration with the EU and cooperation with NATO were named among the foundations. Regarding threats, their list was seriously updated and improved. There were hybrid warfare, the military potential of the Transnistrian region of the Republic of Moldova and separatists sentiments, the illegal stationing of the Russian armed forces in the territory of Transnistria and their arms stockpiles, propaganda, attacks against critical infrastructure, cyberattacks, further destabilization and continuation of the conflict at the territory of Ukraine, illegal migration, arms trafficking, terrorism, chemical orbiological attacks, economic problems and man-made catastrophes.

In December 2022, Alexandru Musteaţă, the head of the Informationand Security Service of Moldova, said that the chances of a Russian invasion of Moldova remained high and that Moscow did not leave the consideration to make a corridor to Transnistria from Crimea. He said that such an attack could be in 2023, but it all depends on the situation in Ukraine.

The words of such a high-level politician in public mean that the country is preparing for possible scenarios of Russian aggression despite its neutral status. This was confirmed later by the Prime Minister of Moldova.

At the same time, the Republic of Moldova had not paid significant attention to its military development within the last decade. Despite the unresolved conflict, due to its neutral status and geographical location ,the efforts have been predominantly concentrated on solving challenges to border security, smuggling, trafficking, or domestic security of the country.

At the beginning of the 2000s, the Armed Forces of Moldova comprised approximately 8500 personnel (including administrative and medical staff). In 2007, the Parliament shortened this number to 6500, plus additional 2300 civilians. Yet 12000 are considered reserved forces. By different data, currently, Moldova has quite outdated but functional 21 aircrafts, 10 tanks, and around 400 armoured vehicles. Also, there are approximately 20 helicopters, including 4 attack helicopters, 25 rocket projectors, 9 self-propelled artillery and 69 towed artillery.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 partially changed Moldovans’ perception of security and made the government turn their attention to the issues of hard security and military cooperation. In April 2022, Moldovan President Sandu announced that the country needs to make serious financial and logistical efforts to build a professional, modern and well-equipped military in order to be able to face the many security challenges in the region. The Speaker of the Parliament confirmed that they are ready to evaluate the possibility of purchasing arms not only from the current partners but also from friendly states. Moldovan Foreign Minister Popescu said that the country’s neutrality did not imply demilitarization or self-isolation and did not mean indifference toward international law or towards civilians being bombed. “Neutrality means that we need a strong, well-equipped army that can defend its citizens,” – the statements previously not witnessed among top-level Moldovan politicians. One of the reasons for rhetoric change is increased bullying from the Russian authorities and aggressive statements from the Transnistrian officials, which have become more common since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

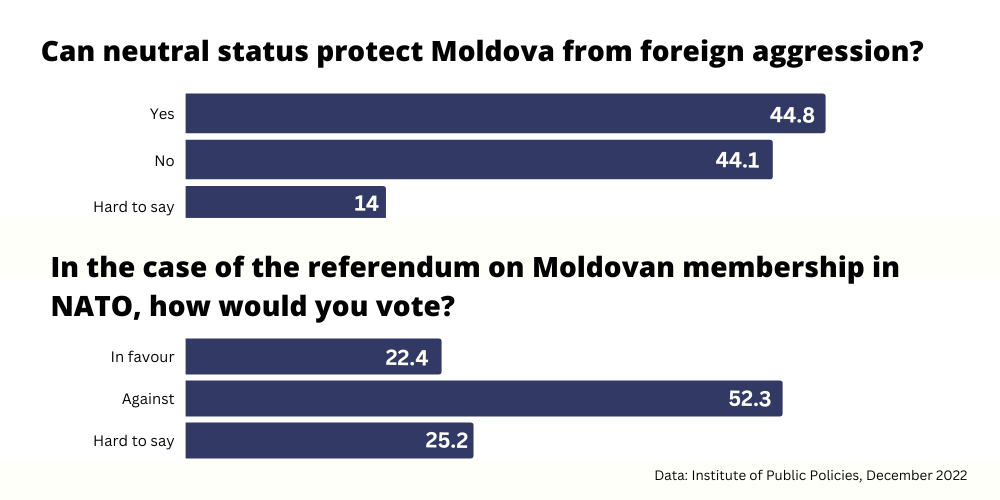

Nevertheless, in December 2022, according to the sociological survey, 44.8% of respondents agreed that neutral status could protect their country, while 41.1% strongly disagreed with this. In the case of the NATO referendum, 22.4% were ready to vote in support of NATO membership for Moldova, while 54.4% would vote against it.

Underfinancing of the Moldovan Armed Forces has always been on the agenda of the government, however, opinions of the top politicians differed. Some considered that due to its neutral status, Moldova could dismantle its Armed Forces as it did not plan to attack anybody, others – believed that financing should be increased and the Armed Forces modernized according to the needs. For 2022, Moldova allocated to defence spending 0.3% of its GDP or 773 million lei (USD 42 million).

As a neutral state, there are limited possibilities for additional military support or financial aid for military purpose available for Moldova. Thus, Moldova has been a member of the NATO Partnership for Peace program, participating in some joint exercises, getting Individual Partnership Action Plan (since 2006), and providing focused country-specific advice on defence and security-related reforms. Supporting civilian authorities (e.g., Trust Fund for the Destruction of Pesticides or development of civil preparedness), Science for Peace and Security program, including in the sphere of cyber defence and gender equality, defence interoperability and capability building, defence education and planning process, – all these were among top priorities but without the high intensity of activities.

The EU came much later as a security actor. In addition to the long-term existing EU Border Assistance Mission to Moldova and Ukraine, in December 2021, the EU granted EUR 7 mln financial support for the development of military medicine. And already in June 2022, the EU decided to allocate EUR 40 mln from the European Peace Facility to modernise the Armed Forces of Moldova. The assistance measures will strengthen the capacities of the Moldovan Armed Forces’ logistics, mobility, command and control, cyber-defence, unmanned aerial reconnaissance and tactical communications units by providing relevant non-lethal equipment, supplies and services, including equipment-related training. Moreover, in November 2022, the President of the European Parliament Roberta Metsola, stressed the need for a European defence union to complement NATO in order to support Moldova.

In May 2022, the British Prime Minister said that the UK might give Moldova NATO-standard weapons to stop an invasion by Vladimir Putin. Several times Romania has been proposing defence and military support to Moldova as well. In September 2022, joint Romania-Moldova-USA military exercises took place in Moldova. In January 2023, the Moldovan armed forces received the first PIRANHA-3H armoured transport vehicles funded by the Enable and Enhance Initiative of the German Federal Government. A total of 19 vehicles will be provided from industry stocks, aimed at modernisation of the defence capabilities of Moldova.

Several incidents of Russian missiles crossing the territory of Moldova or their remains falling at its territory that happened in autumn 2022-winter 2023 highlighted a significant problem of the air-defence absence in Moldova.

In December 2022, Ukraine and Moldova agreed to improve cooperation in air-defence, however, Ukraine cannot defend the territory of the neighbouring state in case of a direct attack against Moldova. Moreover, as a significant part of the border is controlled by the unrecognized Transnistrian Republic, it can be challenging.

Also, in December 2022, the Moldovan Government decided to increase the military budget of the state by 68% compared to 2022, a significant part of which should go for the air-defence. Still, this number will be just 0.55% of Moldova’s GDP.

The Transnistrian conflict that saw its hot phase at the beginning of the 1990s, de facto, continued in a “frozen” state and became both an instrument of Russian influence and a reason for its involvement.

Officially Russia is a guarantor of peace and a mediator in the Moldovan-Transnistrian conflict. As for now, there are two types of Russian military stationed in the country (both in Transnistria). There are 400 peacekeepers within the trilateral peacekeeping forces initiated with OSCE support. Another 1500 Russian military are stationed there illegally to protect the old ammunition storage facilities left after the Soviet Army. The latter must be withdrawn according to the OSCE Istanbul Summit Decision and obligations taken by Russia in 1999, however, the Russian Federation is regularly rejecting to do so. The Russian Federation controls separatists in Transnistria, with most of its inhabitants having Russian passports.

Before 2014 all military supplies took place through the territory of Ukraine, including personnel rotation. After 2014 this practice was terminated. Thus, a significant part of the military personnel are local inhabitants who have Russian passports.

Compared to the Moldovan Armed Forces, the Transnistrian region has a bigger armed formation, up to 7000 personnel. There are four brigades – two on the South in Tiraspol and Bender, one in the centre – in Dubasari, and one in the South in Ribnita, however, they have not had a full composition, so lacking personnel. There is also artillery, special forces, military intelligence, tank units, etc.

Ministry of state security and local police have the capacity tobe involved in military actions as well. Since 2014 it has been an increased number of military drills, including joint with the Russian forces stationed in the region, many of which had scenarios that demonstrated the preparedness for the attacks not only from Moldova, but also Ukraine. Still, while the large amount of Russian troops in the territory of Moldova is staffed by locals (for whom it is just a source of income but not a loyalty), since mobilisation started in Russia in the autumn of 2022, fewer and fewer of the Transnistrian inhabitants would like to renew their contracts with the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation.

Vulnerability of the Political Elites

The President of the Republic of Moldova Maia Sandu and pro-Presidential party PAS – Party of Action and Solidarity which has the majority in the Parliament have an explicitly pro-European agenda (contrary to the previous pro-Russian President Igor Dodon and the Party of Socialists of the Republic of Moldova which had the majority in the previous convocation of the Parliament).

The negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, followed by the economic effects of war in neighbouring Ukraine, an inflow of war refugees and Russian pressure in the energy sector caused vulnerability of the Moldovan society, though.

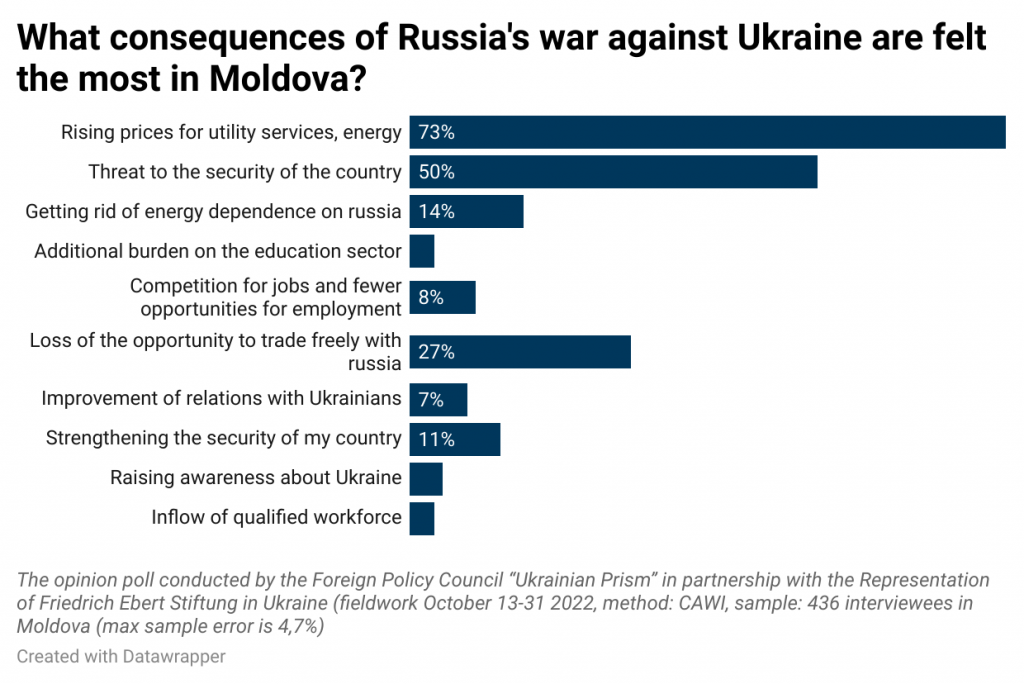

According to the results of the opinion poll conducted by the Foreign Policy Council “Ukrainian Prism” in partnership with the Representation of Friedrich Ebert Stiftung in Ukraine (fieldwork October 13-31 2022, method: CAWI, sample: 436 interviewees in Moldova (max sample error is 4,7%)), the majority of respondents from Moldova feel the consequences of Russia’s war against Ukraine in their country – more than 80% of people in Moldova. 73% of Moldovans feel the rising prices of utility services and energy, 68% – rising prices for goods, and 50% feel threats to the security of the country.

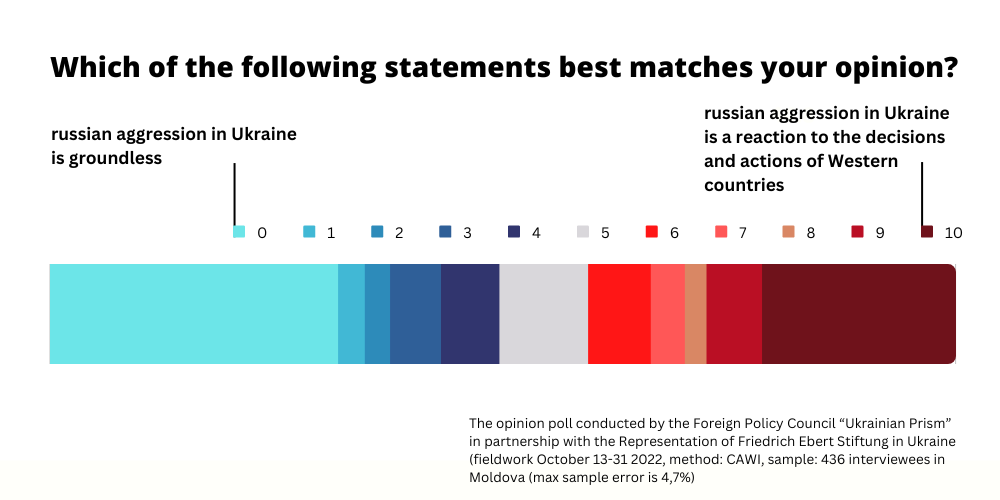

The society brain-washed by Russian media narratives, in many cases, fails to assess the causes and roots of the problems. According to the results of the above-mentioned opinion poll,

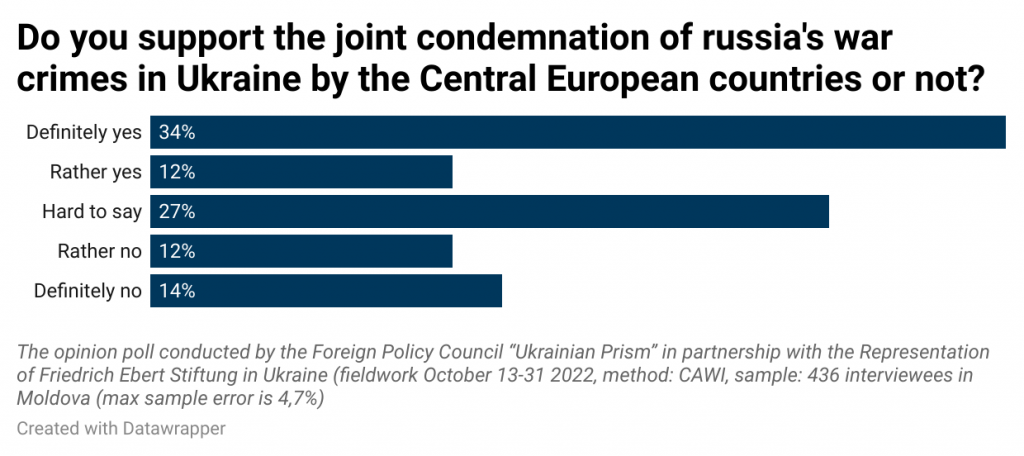

41% of respondents from Moldova rather agree with the statement that “Russian aggression in Ukraine is a reaction to the decisions and actions of Western countries”, while 26% definitely or rather do not support the joint condemnation of Russia’s war crimes in Ukraine.

The opposition parties used the emerging economic and social problems as the pretext for arranging protests and demanding the resignation of the country’s pro-Western government. Most protests have been organized by the opposition party of Ilan Shor, a Moldovan businessman convicted of fraud in connection with a USD1 billion theft that disappeared from three Moldovan banks.Another suspect in that fraud is a business tycoon Vlad Plahotniuc who had an immense influence on Moldova’s previous government and is currently outside Moldova.

Importantly, the social protests organized by Ilan Shor are inspired and propelled by Russian Federation.

The Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) took action to counter the Government of the Russian Federation’s (GoR) persistent malign influence campaigns and systemic corruption in Moldova by imposing sanctions on Ilan Shor for capturing and corrupting Moldova’s political and economic institutions and acting as instruments of Russia’s global influence campaign,

which seeks to manipulate the United States and its allies and partners, including Moldova and Ukraine.

In advance of the 2021 Moldovan parliamentary elections, Russia planned to undermine Moldovan president Maia Sandu and return Moldova to Russia’s sphere of influence. To support this effort, Shor worked with Russian individuals to create a political alliance to control Moldova’s parliament, which would then support several pieces of legislation in the interests of the Russian Federation. As of June 2022, Shor had received Russian support, and the Shor Party was coordinating with representatives of other oligarchs to create political unrest in Moldova to weaken Maia Sandu and pro-European Government formed after the elections. In June 2022, Shor worked with Moscow-based entities to undermine Moldova’s EU bid as the vote for candidate status was underway. Further, Ilan Shor was added to a new UK sanctions list.

The Russian FSB has invested tens of millions of dollars from some of Russia’s biggest state companies to cultivate a network of Moldovan politicians and reorient the country toward Moscow, the documents and interviews collected by the Washington Post indicate. One senior Russian politician praised the protest organizer, Ilan Shor, as “a worthy long-term partner” and even offered the Moldovan region led by Shor’s party a cheap Russian gas deal, according to Shor’s press service.

After that investigation of the Washington Post and sanctions applied by the US and the UK, the Moldovan General Prosecutor’s Office and the Intelligence and Security Service, SIS, announced investigations into interference by Russian intelligence in the country’s domestic politics. Law enforcement investigation was aimed at probing alleged illegal financial support and expertise provided by Russian FSB officers and political experts to pro-Russian political parties in Moldova and efforts to overthrow the pro-Western regime and reorient Moldova towards Russia.

Apart from explicitly pro-Russian Ilan Shor, a few more political parties spread pro-Russian narratives and arguably had direct financing from Moscow. Among them is the Communist Socialist Electoral Block (BECS),

which allegedly received financing from Russia and whose ex-leader, ex-President Igor Dodon, is known for his close ties with Moscow .#KREMLINOVICI – a joint investigative project of RISE Moldova and the Dossier Center, back in 2020, collected the data from the so-called Chernov Archives (a folder with files which the Dossier Center obtained in an information leak from the Moldova affairs office in the Putin’s administration) and Igor Dodon’s BlackBerry (the Moldovan president’s BlackBerry which Mr Dodon used until mid-2017 and which has been passed to RISE Moldova by unknown persons, via an unknown intermediary).Both referrals have been confirmed as reliable by several independent sources. The investigation proved that an office with Russian “consultants” existed in Moldova. Socialist Party lawmakers and a former aide to Prime Minister Ion Chicu were frequent visitors to that office.

Also, some Moldovan politicians were engaged in collaborative activities with the Kremlin’s consultants for years, and Igor Dodon even had Moscow to review his speeches for international events. (Ex)-President Dodon or affiliated with him organizations have been often under journalist investigations or involved in scandalsthat connected him to Russian financing. In November 2022, a Moldova journalist received access to the bank operations of the NGO “Moldova-Russia business union”, confirming that from October 2021 to April 2023, they received from Russia six tranches of USD 300 thousand. All these tranches coincided with Mr Dodon’s strong anti-Western and pro-Russian statements.

Similarly, rather popular political movement in Moldova, Usatii’s Our Party, failed to get into the Parliament, it also demonstrated pro-Russian sentiments and initiated a referendum among Moldovans on whether they want to join the EU, the Russian Custom’s Union, or remain independent.

Paradoxically, pro-Romanian parties in the Republic of Moldova advocating unification with Romania may also cause political environment turbulence.

Although their level of support is rather low (at the parliamentary elections in 2021 the Democracy at Home Party gained 1.45 %, the Alliance for the Union of Romanians gained 0.49 %, the National Union Party gained 0.45 %) and therefore, they are not represented in the Parliament of the Republic of Moldova, pro-Russian forces may use their narratives to intimidate and mobilize the Russian-speaking population of the Republic of Moldova and stipulate their pro-Russian and pro-Soviet sentiments There is also an emerging risk coming from relatively new political actors in the Republic of Moldova – Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR), which exists both in Romania and the Republic of Moldova. In Romania, this political party has passed the threshold and is a parliamentary political force. It is a conservative movement which speculates on family, church, and national values to appeal to vulnerable populist voters, and this may eventually cause another challenge (even if the AUR analogue in Moldova does not immediately become popular, they have a chance to become political allies of the PSRM and the Șor Party). Moreover, they will go for the centre-right electoral field, despite the pro-European forces’ interests.

Besides, the goals and objectives of the National Alternative Movement remain unclear. It was created at the end of December 2021 and led by Chisinau Mayor Ion Ceban. The party is in opposition to the current government of the Republic of Moldova, and originally Mr Ceban was a member of PSRM. Although migration between the political parties is usual practice for the Republic of Moldova, Mr Ceban’s integrity, as well as the narratives the party spread, deserve attention.

Under such circumstances, Moldovan authorities are forced to act in the legitimate defence of state interests by investigating leading figures of the BECS and Shor. The ex-President Dodon, who quit the political leadership of Socialists but still remains one of the opinion-makers promoting the political interests of this political force, is being investigated for unlawful personal and family enrichment, illegal financing of the Socialist Party through him and state treason (Kremlin funding). Corneliu Furculita, an MP representing Socialist Party, is being questioned for unlawful enrichment, part of it possibly connected with the acquisition of two television channels with Russian-tainted funds, and Marina Tauber, chair of the Shor Party’s parliamentary group, has seen her parliamentary immunity lifted and has been in pretrial detention since July 23, 2022, charged with falsifying the party’s 2021 financial report and accepting funding from an organized criminal group.

However, less attention is paid to new political actors that potentially can undermine the European agenda of the Republic of Moldova, which will benefit Russia both in the Republic of Moldova and in the region and this shortcoming is to be fixed.

An important issue that has to be tackled is the issue of Gagauzia. The region is vulnerable towards Russian influence due to the overwhelmingly pro-Russian and often secessionist views of its population.

Back in February 2014 the local referendum organized in Gagauzia indicated that 98% of its population are in favor of the secession from Moldova should there be a change in statehood (which can be interpreted both as uniting with Romania or joining the EU). Now the relations between the pro-European government and local elites remain tensed. In August 2022 Gagauzia intended to bypass Russian embargo on goods from the Republic of Moldova by direct bilateral talks between Comrat and Moscow. Irina Vlakh, the leader of the region visited Russia after February 24, 2022. The situation may eventually change in 2023. The next election of the Bashkan (governor) of Gagauzia will be held on April 30, 2023. However, bearing in mind the circumstances, the likelihood of electing another pro-Russian Bashkan is high.

Economic Vulnerability

In December 2022, the government of the Republic of Moldova proposed, and the Parliament passed the budget forecasting economic growth of 2%, inflation of 15.7% and a deficit of 6% of the GDP. That is a very optimistic forecast bearing in mind that the government revised the assessment of the 2022 economic growth forecast to zero from the previous 0.3%, as a result of the negative impact of the Russian war against Ukraine and rising global energy prices. Compared to 2021 almost 14% growth, nowadays, the economics of the Republic of Moldova is almost collapsing.

According to the assessments of the International Monetary Fund, large amounts of money have been borrowed to compensate for the impact of the external shocks,and therefore there is a huge deficit of costs for domestic reforms, and the accumulating debt will consume future revenue that should have been spent on development. Before the beginning of the full-scale Russianinvasion of Ukraine, the IMF projected that Moldova’s ratio of public debt to GDP would hit 40% in 2022, from 27.9% in 2019. The fund assessed anything over 45% as unsustainable for Moldova.

The factor that causes the multiplication of the economic threats is Moldova’s dependence on remittances usually sent back home by Moldovans working in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. Due to obvious reasons, the respective figures will decrease.

However, the key factor that undermines the Moldovan economy is heavy dependence on the supplies of gas from Russian Gazprom combined with dependence on a gas-fired power station located in Transnistria and operated by Inter RAO UES PJSC, which covers up to 80% of consumption. 50% of MoldovaGaz, the company that ensures the inflow of gas to the Republic of Moldova, is owned by Gazprom, whereas another 13.4% are controlled by the de facto Transnistrian administration.

Starting from 2021, Russian Gazprom has been trying to force Moldova into signing a new contract to purchase gas at high prices. In November 2022, Gazprom accused Ukraine of keeping gas supplies heading to Moldova and used that pretext to threaten both countries by reducing gas supplies to Moldova that pass through Ukraine. Both Ukraine and Moldova denied any accusations.

High dependence on Russian gas and electricity produced by the power plant in Transnistria is often used as a tool of pressure on the Moldovan government. It limits the willingness of Moldovan elites to solve the Transnistrian problem (shutting gas deliveries to Moldova will also result in shutting electricity and heating for Transnistria, which is not considered an option unless Tiraspol is controlled by pro-Russian proxies) and even inspires them to compromise like providing environmental license for the scrap metal processing plant in Ribnita that plays an important role in the Transnistrian economy.

Besides, it even prevented Moldova from explicit support to Ukraine at the early stages of the full-scale Russian invasion. Initially, Moldova was unwilling to sanction Russia, explaining that the potential sanctions could have put social pressure on the government resulting in it being overthrown. Initially, the Republic of Moldova abstained from launching sanctions against Moscow, and therefore it was not enlisted as an “unfriendly country” by Russia.

Summarizing, the economic vulnerabilities of the Republic of Moldova and its dependence on Russia have political implications because they are weaponized by Russia and influence not only the domestic Moldovan social and political agenda but also its positioning in the international arena.

Informational vulnerability

According to Reporters without Borders, Moldova is ranked 40 out of 180 in the global index of media freedom. Reporters without borders note that Moldova’s media are divided into pro-Russian and pro-Western camps. Oligarchs and political leaders strongly influence their editorial stances. Journalists are regularly insulted and intimidated by government officials and political leaders. Their militants often resort to cyber-harassment against reporters considered to be foes. Journalists’ access to Transnistria, a separatist eastern province backed by Russia, requires special accreditation.

Until its suspension by the new parliamentary majority in 2021, the Audiovisual Council granted broadcasting licences to television networks tied to the Party of Socialists, which assured the re-airing of propaganda produced in Russia.

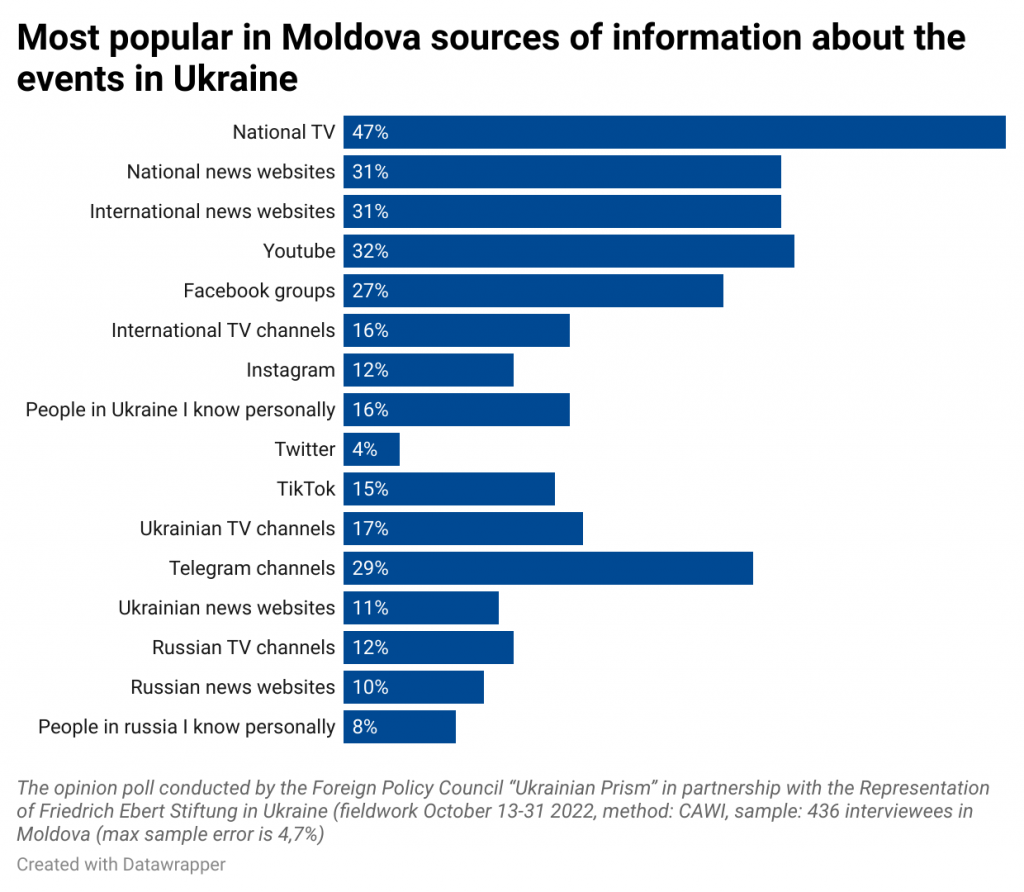

According to the opinion poll conducted by the Foreign Policy Council “Ukrainian Prism,” the most popular sources of information about events in Ukraine in the Republic of Moldova are national TV (47% of respondents), YouTube channels (32%) and national and international websites (31%). However, 29% of respondents above all trust anonymous Telegram channels, 12% Russian websites and 11% Russian TV channels.

The latter figures coincide to some extent with the number of Russian-speaking minorities in the Republic of Moldova. In this regard, it is important to note that the Moldovan policy towards minorities was ill-designed and, instead of promoting the minority languages rather invigorated minorities that were not Romanian-speakers to shape the unified group of Russian-speakers (since Russian used to be the lingua franca during the Soviet rule) vulnerable to Russian propaganda.

Even within the wider audience, the media content produced by Russian state TV channels Perviy Kanal and RTR have consistently been among the most popular in Moldova. As Clindendael points, such content was first re-broadcast by Plahotniuc-controlled PRIME TV, but later taken over by a channel of a media holding that is close to the PSRM, Media Invest Service, which owns Accent TV and Primul. Media Invest Service is 51% owned by Igor Chaika, the son of Russia’s prosecutor-general.

Underfinancing of the media sphere in Moldova and a small advertisement market makes it dependent on the owner’s support and influence while not allowing independent media to be developed. Also, the inability to produce significant local content made the media sphere dependent on foreign entertainment content that, for decades, has been Russian. As Russian entertainment and cinema became highly politicized, it also impacted Moldova.

The EU is already active in the media in Moldova, and supports mass media alongside improving the media literacy of the citizens of Moldova. Counter disinformation in the EaP, including in Moldova, is being assured by the EUvsDisinfo project of the EU’s East StratCom Task Force.

In November 2022, it became known that the Telegram channels of Moldova’s top-politicians, including President Sandu, were hacked, and information was leaked. According to the officially announced suspicious, this could be done by the Russian Federation services to discredit the pro-Western government.

On May 4, 2022, the EU adopted a new crisis response measure of EUR 8 million to strengthen the Republic of Moldova’s resilience to the crisis situation resulting from the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine. This funding was aimed at supporting national efforts to increase the country’s cyber and information security.

On July 6, 2022, the Government of Moldova adopted the decision to create a Coordinating Council for Information Security (Council). The Council has consultative and operational responsibilities, to estimate the level of danger to information security at the national level and propose actions to resolve the reported incidents.

The Council’s activity is focused on four segments, with four different groups responsible for each segment:

1. Cybernetic – identifying and examining security incidents;

2. Operational – identifying news that could affect the country’s information security;

3. Media – assessing the factors that could harm the institutional integrity of the media on virtual platforms;

4. Civic-private – with different responsibilities, including the presentation of cases of human rights violations regarding free access to information resources.

The Moldovan ban on Russian news programs (Sputnik was shutdown on February 26, 2022, whereas in June 2022, the Parliament passed a new Law on Information Security that banned news and analytical programs from non-ECTT signatory countries) strengthened resilience towards Russian propaganda. Later, in December 2022, Moldova suspended the broadcast licenses of six television channels. The decision to revoke the licenses was announced by Moldova’s Commission for Exceptional Situations, which was established following Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine. Moldovan President Maia Sandu called the suspensions “an important step to prevent attempts to destabilize” the country

Successful Cases of Discovering and Deterring Russian Influence

For a long time, the opposition to the malign Russian influence has been conducted predominantly by civil society organizations and investigative journalists. Intensification of such activities was observed during the election campaigns, as Russian attempts to influence election results were always strong and often not even hidden.

The governmental activities were absent, while the President of the country was Igor Dodon, a pro-Russian politician. Still, since 2018 some attempts have been made in the information sphere, however, under the constant political conflict between the parliament and the president regarding such legislation. So, the amendment to the Audiovisual Code of Moldova, also known as the “anti-propaganda law” (came into force in February 2018), prohibited rebroadcasting in the Republic of Moldova news, talk shows, and other media products from the Russian Federation. The fact that Russia has not ratified the European Convention on Transfrontier Television was used as an official reason. In December 2020, the parliamentary majority formed by the Socialists and the Shor Party cancelled the law and the ban on broadcasting Russian information and military analytical programs in the Republic of Moldova.

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the Moldovan government and presidency (already representing pro-European forces) intensified their work to counter Russian influence. It started with the prohibition to advertise on Russian re-transmitting channels in the autumn of 2021.After the introduction of the Emergency state in Moldova, the government adopted several legislations limiting Russian influence in media. Among them is the prohibition of transmitting news and analytical programs produced in countries that didn’t ratify the European Convention on transfrontier television of the Council of Europe (meaning Russia); the prohibition of posting advertisements at the Russian re-transmitting channels. These legislations were prepared back in December 2021 but quickly adopted with the start of the Russian-Ukrainian war.

In March 2022, Moldova’s Security and Intelligence Service blocked numerous Russian information channels, such as RT and Sputnik, and pro-Russian websites, such as flux.md, iurierosca.md, rosca.md, gagauznews.md, ehomd.info and rta.md the reason mentioned “hate speech and war propaganda”. The pro-Russian Socialist Party of Moldova issued an official statement condemning these restrictions.

Among the civil society organizations that dealt with the issues of countering malign Russian influence, especially in information, political and national security issues, it is worth mentioning Watchdog (main priorities – domestic politics, elections, and information security), Foreign Policy Association and the Institute for European Policies and Reform (IPRE) (main priorities are foreign policy and European integration).

Media organizations and independent portals also tried tobe involved. During the COVID-19 outbreak, the Independent Journalism Center of Moldova published monitoring of the media activities regarding the spread of fake news, which were actively spread by Russian or pro-Russian media outlets in Moldova.

RISE Moldova is an example of investigative journalism that successfully uncovered Russian influence during the elections in Moldova in 2020. Special reports under the joint name “KREMLINOVICI” consisted of many parts uncovering media, politicians and Russian spin-doctors working in Moldova were published and translated into Russian and English, and widely quoted. They have not limited themselves just to the election topics, political corruption, business connections with Russians, offshore and financial frauds, where Russian traits, etc., also were observed.

The analysis of the probability of Russian reflexive control operations

For the last 30 years, Moldova has been under significant Russian influence caused by the results of the war at the beginning of the 1990s, economic and energy dependence, as well as melding into a political process. Despite the neutral status of the country, the Russian Federation has continued to work significantly on anti-Western sentiments, bringing cleavages in the society, some of which have an ethnic and historical background.

Despite an increased understanding of those challenges and threats in the Republic of Moldova, belated attempts to counter Russian influence and covert operations, elements ofhybrid warfare, as well as pro-Russian proxies still active in politics, Moldova remains in a high-risk zone for malign Russian influence.

Russian tactics in Moldova rarely tend to be sophisticated and usually are quite blatant and straightforward, considering that open pressure and support of the pro-Russian political forces is the best possible method. Among the Russian tactics are: open propaganda through Russian media (till March 2022, when many were closed), support of the pro-Russian media in Moldova, support and sometimes control over local proxies – Moldovan politicians of the left-wing political spectre, economic and energy pressure, support of the Transnistrian Moldovan Republic and military forces stationing there, influence over Autonomous region of Gagauzia, provoking clashes between Russian and Romanian speakers, etc. The following are some of the spheres where we can expect increased Russian activities.

Raising the issues of interethnic contradictions and manipulations of ethnic minorities’ political preferences. The diverse ethnic composition of Moldova and its complicated history of coexistence with Romania is an issue for manipulation and MFI. While a significant majority of the Moldovan citizens are Moldovan/Romanian ethnically, however, there is an autonomous region of Gagauzia (inhabited by the Orthodox Christian Turkic nation of Gagauz) that is under the significant influence of Russia. Transnistria also is divided approximately 30/30/30 between Russian, Moldovan, and Ukrainian ethnic groups. In Moldova itself, the language usage of Russian or Romanian/Moldovan plays an important disturbing role.

Support of the pro-Russian political parties and politicians, and their associates. The Russian Federation has not limited its support only to the Socialist Party of Moldova but puts the eggs in different baskets, sponsoring other local leaders and political movements. If at the previous elections, they slowed down a bit such intrude into the political process (still being active but hoping that both presidential candidates would not break relations with Moscow), so after the EU candidacy status for Moldova and crystallization of Moldova’s position regarding Russia-Ukraine war, one can expect an intensification of the support of the pro-Russian forces aiming to change political leadership of the state. These activities will also be aimed at political destabilization and undermining trust in the President.

Provocations remain the main threat at the territory of the Transnistrian region. As the Russian Federation seeks both reasons for its deployment in Transnistria and mobilization of its inhabitants in the Armed Forces, as well as control over political elites, false flag operations, border incidents or military provocations remain in the category of high-possibility risks. In addition to provocations against Moldova, one can also expect the use of Moldova territory for provocations against Ukraine. Russian armed forces, together with stockpiles of ammunition, cannot be considered a significant threat, considering their number and maintenance condition, but still, as an auxiliary component or trigger point, they can be efficient.

Energy pressure that may intensify by the beginning of 2023. Moldova-Russian energy negotiations in the autumn of 2021 became the most difficult challenge for Moldovan foreign policy.The problem consisted of two parts – a new contract and an increased price for gas, and an audit of the “historical debt”, which Russian claims tobe USD 709 million. The new five-year contract was signed in November 2021 after serious blackmailing from the Russian side, threatening to stop supply. The contract included a condition to conduct an audit by May 2022. At the same time, unrecognized Transnistria receives gas according to the Moldova contract but does not pay for it, money received from the population is accumulated in the special account used by the Transnistrian leadership to cover a budget deficit. This dept, as of now, is USD 7,5 billion. Anytime Russia may claim this debt to be paid by Moldova, as it has already done repeatedly.

Influence through the church structures.As Moldovan Orthodox Church is under the control of the Russian Orthodox Church and, in many cases, has been a provider of their narratives in Moldova, one can expect wider use of this instrument in Russian covert operations. The reason behind is weak control over a religious sphere, and respecting the freedom of religion in Moldova.

Spreading propaganda, fake news andpro-Russian narratives through social networks and media. Despite the closure of some media portals and outlets, they can easily be relaunched under different names, which has already been done many times. Spreading the information through anonymous telegram channels and groups, bulk websites is common. Also, the ability to watch Russian media through satellite, especially in Gagauzia and Transnistria, as well as the pressure of some political parties to reopen Russian media in Moldova, should be considered.

Cyber attacks remain among the top probabilities for Moldova, considering the low level of cyber security and just recent prioritisation of this topic among national security concerns. There are more chances to have such attacks against the governmental or banking structures than massive virus or malware attacks, as Moldovan society is not significantly digitalised yet.

Direct blockade of the Moldovan export, including through Gurgulesti port, similar to what was done with Ukraine, is not possible due to the ability to export through the Moldova-Romania border and the geographical location of the port. Still, Moscow may manipulate with Moldovan export to Russia, rejecting it, boycotting, or imposing sanctions. This will definitely accompany by an intense information campaign on the negative consequences of Moldova’s EU integration and the necessity of improving relations with Russia.

Recommendations on resilience, and managing vulnerabilities in the areas sensitive to Russian malign influence

1. Transnistrian Conflict. Moldovan neutrality did not ensure the withdrawal of Russian troops from the territory of Moldovan Transnistria. Neither 5+2 format proved to be efficient enough in particular, bearing in mind the fact that the official statuses of the participants do not correspond with their de facto role in the process (neither Russia is a guarantor of peace and mediator nor the EU and the US remain pure observers). Therefore, the process of Transnistrian settlement has to be reconsidered. The format has to be reshaped in compliance with the current status of the parties with the possibilities of further internationalization of the settlement process. Also, the Republic of Moldova and its international partners should consider the validity of the 1992 seize-fire Agreement bearing in mind the constant violation of Article 4 of the Agreement, which obliged the 14th Army to keep neutral. The question of the peacekeeping mission status change should be raised again, so to initiate a long-distance process of transforming from a military into a political one.

2. The Republic of Moldova and its international partners should think of elaborating the plans for assuring neutrality in compliance with its internationally recognized attributes outlined by the humanitarian law provisions. The calls to the Russian Federation to withdraw its military personnel as agreed in 1999 should be intensified with the possibility of raising an issue not only in the OSCE, but also in the UN and other international institutions.

3. Bearing in mind the vulnerability of the political elites in the Republic of Moldova, the political literacy of the citizens of Moldova has to be ensured, and transparency of funding of the political forces has to be enhanced. The political parties should face a screening process each electoral cycle, and in case of proven funding from foreign sources and/or sanctioned persons/entities, should be deprived of the right to participate in the elections.

4. Civil society’s capacities to ensure democracy watchdog function have to be strengthened. Funding consortiums of the organizations from the countries vulnerable to malign Russian influence would be of added value since methods applied by Russia for corrupting elites are often similar.

5. The Republic of Moldova should, by legal means, ensure the transparency of funding of media and media-ownership to limit malign Russian influence and improve media accountability and responsibility.

6. The EU and other international organizations should consider supporting investigative journalism and independent media development in Moldova.

7. The informational vulnerabilities often aimed at the Russian-speaking population have to be fixed by a strategic rethinking of ethnic policies in the Republic of Moldova. The previous practice of using the Russian language as the language of interethnic communication failed and resulted in the Russification of the Ukrainian, Bulgarian and other ethnic communities in the country. Instead, the instruments for cherishing national identities alongside loyalty to the host state have to be elaborated. These endeavours should be supported by the government of the Republic of Moldova, governments of the kin-states and the European Union.

8. For the interim period, launching the media for Russian-speaking representatives of minorities can be considered an option. However, it should not be influenced by Russian propaganda. Inclusiveness of the editorial policy may eventually lead to a situation when the state or donors’ funded media will be used for spreading a Russian narrative which is not an option in the current circumstances.

9. Moldova 1 TV station can do better and needs to be reformed and upgraded to produce informational and entertainment content for both the Romanian-speaking population and minorities in their own languages. Besides, media ownership transparency in Moldova is to be assured and regularly monitored, and the EU Programs to enhance media-literacy have to be boosted.

10. Although Russia may seem to be straightforward in its hybrid attacks, one may not exclude operations through intermediaries, either brand-new entities and/or political forces or by propelling anti-European narratives from which Russia also benefits. Therefore, monitoring and screening should be applied not only to the “usual suspects” but also to the actors leaning toward extreme rhetoric and activities, even if they are not explicitly pro-Russian.

10. Apart from growing trade with the EU, the Republic of Moldova and its partners should also ensure diversification of supplies of gas and electricity, which are currently overwhelmingly controlled by Russia. The usage of Ukrainian gas storage for accumulating Moldovan gas is a good practice worth to be promoted. However, alternative routes of supplies are to be considered. In this regard, the growing Turkish-Romanian cooperation on assuring supplies of LNG to Romania has to be studied from the perspective of feasibility for Moldova and the perspective for Ukraine.

11. Cooperation in a cyber security sphere should be launched with Ukraine and Romania with a possible NATO involvement (e.g. creation of the NATO Trust Fund).

This publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union and the Black Sea Trust for Regional Cooperation. Its contents are the sole responsibility of Foreign Policy Council “Ukrainian Prism” and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union and the Black Sea Trust for Regional Cooperation.