The article touches issues of Ukraine-Moldova relations and considers pros and cons of the realism-oriented and liberalism/constructivism-oriented approaches in the bilateral relations. The author argues that liberal constructivist approach will result in win-win results whereas the realism-oriented approach can be counterproductive and thus a task of the civil society is to invigorate governments to make joint efforts grounded on common values instead of behaving using the perspective of rational egoism.

Sergiy Gerasymchuk for UA:Ukraine Analytica

For the Ukrainian government the relations between the Republic of Moldova and Ukraine have quite often been overshadowed by relations of Ukraine with bigger players e.g. the United States, the EU and Russia. Quite regularly Moldova was perceived by the Ukrainian experts and officials as a state too tiny to influence regional developments and too weak to shape the agenda of the bilateral relations.

In relations with Chisinau, Kyiv often perceived itself as a regional power able to impose its own agenda and to be rather a mentor and custodian than an equal neighbour.

However, such an approach is false due to a number of reasons. First, despite Moldova’s small size, relatively weak economy and arguably little influence in the region, Moldovan government is a tough negotiator, often guided by the rational egoist approach. Therefore, a number of issues in the bilateral relations of Ukraine and the Republic of Moldova remain unresolved, e.g. long lasting property issues related to resorts inherited from the USSR and a hydroelectric station, an issue of the border demarcation etc. These existing issues are harmful for the relations and in the middle-term perspective might have a “spill over effect” – deterioration of the relations in the field of joint efforts for the European integration, misunderstanding in the process of the Transnistrian conflict settlement, economic tensions and joint participation in the regional projects.

Secondly, there are too many similarities in Ukrainian and Moldovan politics: they are both corrupted and the system of justice is underdeveloped.

In addition, fights between pro-European political parties in Moldova give ground for increased ratings of the revanchist political powers and discredit the idea of the European integration itself, and it might become a case for Ukrainian pro-Europeans as well. Thus, better understanding of Moldova gives some clues for understanding Ukraine and vice versa.

Thirdly, Moldova for more than 20 years has faced a challenge of separatism inspired by the Russian Federation in Transnistria (which has about 450 km of border with Ukraine, not controlled by Moldovan authorities). Moreover, Moscow still keeps military forces in the separatist region of Transnistria and prevents any attempts of peaceful resolution of the Transnistrian frozen conflict. Hence, the Kremlin keeps the Moldovan authorities hooked and making any decisions without negotiating with the Transnistrian separatist leadership remains a complicated task for Chisinau. The Russian Federation clearly stated that it does not want to lose Moldova from its sphere of interests and instead of the European perspective, it promotes another destination for integration – the Customs Union.

Russian authorities manipulate Moldova’s dependence on gas supplies and efficiently use this leverage each time Moldova is making any progress in relations with the EU. Moreover, Moscow is quite good in manipulating sentiments of the Russian-speaking population and suggests the idea of “russkiy mir” (Russian World), as an alternative for further integration with the Western world. Therefore,

lessons learned by Moldova in the Transnistrian conflict as well as lessons coming from the Russian manipulation with public opinion in Moldova in this regard can be of immense importance for Ukrainians. Moreover, it is fair to assume that Moldova is a sort of a “shooting range” for a hybrid warfare for the Kremlin where Moscow is testing methods of discrediting its opponents, invigorating conflicts and fights between pro-Russian and patrioticoriented forces, undermining Moldovan statehood. Therefore, better understanding of Russian methods alongside with testing remedies in Moldova can be helpful for preventing and counterweighing similar scenarios in Ukraine. In order to fill the existing gap in understanding these factors and to have better understanding of the possible future developments in the bilateral relations it makes sense to take a look at all the mentioned issues in detail.

Bilateral tensions

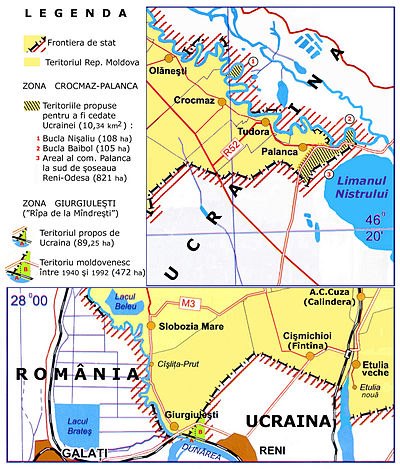

There are a few issues that have caused tensions in the bilateral relations. One of the illustrations is border dispute. Despite the agreements reached back in the 1990s on the exchange of a territory near the village of Giurgiulesti, according to which Moldova gained a status of the littoral state and received a possibility to build up a transport hub on the site, Ukraine in exchange has not received the jurisdiction over the land near Palanka village, although it was a part of the deal.

Ukraine had to agree to a compromise according to which the road near Palanka remains Ukrainian property on the territory of the Republic of Moldova. Moreover, Ukraine is facing a problem of access to some of the Dnistrovska Hydro-electric power plant, which since the Soviet times has some of its technical buildings on the Moldovan side of the border. (Geographical information was the key source for setting and administering the state borders. However, in this case it did not guarantee avoiding misunderstandings and tensions between the states. The delimitation of the Ukrainian-Moldovan border was grounded on the outdated topographical maps with the scale 1:50000 and 1:10000, on which the Hydro-electric plant built in 1985 was not marked at all.)

Another issue that causes concerns of the Ukrainian side is a problem of imposing customs duties to the Ukrainian products, in particular to dairy products, meat and cement. The problem is caused by the fact that the volume of Ukrainian export to Moldova after its reorientation from the Russian market has reached 9,3% of its import in 2015 including 12% of the dairy products (following only Romania and Russia and leaving behind Germany, China and Turkey).

The outcomes were protests of the local Moldovan producers, who requested the Ministry of the Economy of the Republic of Moldova to hold antidumping investigation since prices for the products imported from Ukraine were much lower than prices suggested by the local producers1 (that has become possible due to the significant devaluation of the Ukrainian hryvna and possibility to avoid VAT taxation for foreign companies in the Republic of Moldova).

In response, the Republic of Moldova imposed customs duties and quotas until the end of 2016. The customs duty is increased by 10−20% and therefore Ukraine, which believes Moldovan measures violate the WTO rules and CIS Free trade agreement, is planning to bring the issue to the consideration of the WTO and to impose reciprocity measures.

Besides, Ukraine is wary regarding Moldova’s current negotiations with Russia on lifting Russian sanctions to Moldovan products.

Kyiv suspects that the visit of Rogozin − Russian Vice-PM and the Special representative of the Russian president on Transnistria, planned for July 2016 and the expected task-list for eliminating restrictions on the Moldovan goods export for the Russian market might include some concessions that Ukraine will have to pay for and thus the outcome can be further deterioration of the bilateral relations between Ukraine and Moldova.

One of the initiatives that is under in question is launching a railway connecting Ukraine and Moldova bypassing Transnistria.

The launch of this initiative was expected in summer 2016, including a plan to build the railway segment Berezyne-Besarabka and the repair of Artsyz-Berezyne segment. Such an initiative would result in connecting Moldova with the Odessa port bypassing the Transnistrian secessionist region, uncontrolled by the government of Moldova. However, if relations between the countries deteriorate, the project can be suspended.

The same is true regarding the implementation of the Black Sea Highway Ring initiative. According to the previously reached agreements, some segments of the Highway are to be built in order to connect Ukraine, Romania and Moldova. The initial idea was to connect Odessa and Bucharest by two branches of the highway: via Reni-Giurgiulesti-Galati and via Chisinau and Ungheni. Like in the previous case, in case the relations between Ukraine and the Republic of Moldova deteriorate, the project can be suspended (in particular Giurgiulesti segment). There are high chances that the future of these initiatives and the Ukrainian role in their implementation may be used by Ukraine as arguments to change Moldovan positions and to persuade Moldova to fulfil its commitments.

By applying such an approach, both countries are behaving realistically in the international politics though. However, if the negotiations on sensitive issues continue within the realism pattern they will definitely result in the lack of trust between the governments, a decreased level of cooperation and cooperation in the field of the European integration, and the lack of solidarity in negotiations regarding the Transnistrian conflict settlement.

Both countries would definitely benefit more if they applied liberal and constructivist patterns.

Liberal understanding of the relations between Ukraine and Moldova would result in a win-win approach whereas a constructivist approach would also provide the added value of common identity which is rooted in similar for both countries understanding of the European integration and Western values.

Basically, the leadership of both countries has to come to understanding that they are “in the same boat”, to develop the perception of each other grounded on the common values/ common goal approaches, to implement joint strategies in interacting with the third parties acting in the region, etc. Therefore, what is needed for the improvement of the relations and efficient resolution of the issues in the relations between Kyiv and Chisinau is switching from realist to liberal and constructivist agenda setting and understanding that two nations will benefit much more from cooperating on bilateral issues if such cooperation is grounded on the common values and friendly relations.

Risky similarities in political behaviour and wrongly perceived messages of the Western powers

Current political turmoil in the Republic of Moldova alongside with activities of the Moldovan well-known oligarch and politician Vlad Plahotniuc aimed at “stabilizing” the state, reflect numerous similarities of the political systems in Moldova and Ukraine.

The key similarity is that frequent street protests in Moldova and a high level of the protest potential in Ukraine are rooted in the weak and corrupt state institutions. The key catalyser for the mass protests in the Republic of Moldova was the Moldovan banks theft money affair, which happened back in 2014, when Unibank, Banca de Economii and Banca Sociala got from the National Bank of Moldova the loan of about one billion dollars – which was later transferred to offshore accounts through complex transactions whereas the banks went bankrupt.

In February 2015, a group of civil society activists declared the Manifest of Civic platform “Truth and Dignity” in which it blamed the governmental officials in being involved in the “one billion affair” and for imitation of the implementation of the reforms in the country. Although none of the EU officials supported the demands of the Platform explicitly, the initial idea of the protests was beneficial for the idea of European integration process.

The leaders of the Platform often voiced the same concerns regarding developments in Moldova that the EU officials shared. Furthermore, the activities of the Platform resulted in investigation of the “one billion affair” and even led to the arrest of the former prime minister of the Republic of Moldova Vlad Filat.

However, simultaneously with some impact on fighting corruption in Moldova, the protests of the Platform gave impetus for the development of another sort of protests. Other political forces that tried to get benefits from social unrest and protest mood of the electorate were on the pro-Russian side of the political spectrum: the Red Block, Socialist party headed by Igor Dodon and “Partidului Nostru” – the party headed by Renato Usatii joined the protests. All three players started to combine their efforts in organizing the protests. Whereasthe Platform reached a certain victory in its fight with the government, which, in the opinion of protestors, was only declaring European values6, pro-Russian forces reached their goal in compromising the idea of European integration itself. Whereas the key demand of the protestors was that the corrupted officials should leave, many of these officials happened to be, at least declaratively, pro-Western and pro-European.

Under such circumstances, the steps of the West (the United States in particular) were designed in a pragmatic way. Since Western powers were not in favour of the early elections, which would most probably result in gaining the majority of the seats in the parliament by the pro-Russian forces, they allegedly agreed on the proposal of Mr. Plahotniuc to stabilize the political situation by appointing the government totally controlled by him and his political force. A few days before Moldova’s parliament nominated Plahotniuc’s alleged proxy Pavel Filip to the prime minister’s position, Victoria Nuland, a top-ranking US State Department official, visited Bucharest, the capital of neighbouring Romania, where she declared that Washington was supporting the current government, which was dominated by Plahotniuc’s Democratic Party.

The key reason for such a decision arguably was the desire to preserve the government, which is at least declaratively pro-European and thus appears to be less evil than the possible pro-Russian alternative. (It is noteworthy that the Ukrainian government did not release any sound statement on the developments in neighbouring Moldova).

Such approach of the United States seems to be understandable from the perspective of realism. However, looking deeper into the problem we can discover some negative outcomes. The first one is the disappointment of many Moldovans. They do not perceive the conflict between the opposition and the government as geopolitical, but rather the one related to corruption that threatens democracy. If the West does not recognize this fact, it may lose the credit of trust of Moldovan people.

Another negative impact is the fact that the message of Western powers delivered in Moldova can be wrongly perceived in Ukraine.

The Ukrainian politicians might assume that if just declaring yourself proEuropean works in the Republic of Moldova, the same pattern might be applicable for Ukraine. That would cause the declarative pro-European policy supplemented though with the significant lack of reforms.

Finally, the belief that Moldova should choose the lesser evil, which is Plahotniuc, if shared by the Ukrainian expert community and civil society, would undermine its close ties with the civil society of the Republic of Moldova. During the days of the Revolution of Dignity in Ukraine, the civil society in Moldova sincerely supported Ukrainian counterparts and expressed their solidarity. If the Ukrainian civil society leaders do not support their Moldovan counterparts these days, that will cause damage for solidarity of civil society per se in the region.

Containing these challenges is possible by intensified dialogue between the expert communities of Ukraine and Moldova and joint efforts aimed at ensuring the civil society’s function of a democracy watchdog.

Besides, the West also has tocontribute to the further development of civil society movements and their transformation into the influential political force that would create an alternative to the existing, often corrupted and compromised “pro-European” forces in both Ukraine and Moldova.

The respective policies have to be implemented promptly; otherwise, the existing “lesser evil” will be soon substituted by revanchist powers

that will result in the failure of European ideas in the region and the decline of the Western influence.

Transnistrian edge of the bilateral relations and the challenges it causes

Obviously, the current crisis in the Republic of Moldova has some impact on the developments in the Transnistrian settlement as well. Transnistria is extensively using “destabilization” and the “Romanian threat” discourse to consolidate its society. Since 1990-s the authorities of the breakaway region have been exploiting the thesis about unstable Moldova and the “Romanian tanks” to prove the necessity of being “independent from Moldova” and expecting support from Moscow.

Meanwhile, Moscow is actively playing both with the sentiments of Transnistrian voters and with a geopolitical situation in the region. For example, on 31 March 2016, Russia held the drills for the Operative Group of the Russian military forces in Transnistria, although Moldova is constantly demanding to withdraw Russian troops from the Transnistrian region and the respective declaration was made by the Moldovan authorities on the same day8.

Russia also illegally recruits the soldiers in the Transnistrian region, which is dejure a territory of Moldova, whereas the conscripts are Moldovan passport holders.

That does create the problem of violated international norms, de-facto demonstrates Russian sovereignty over the region, and may potentially cause the situation when Moldovan citizens (passport holders of the neutral state) will be indirectly involved in the military clashes with the third countries.

On 10 April 2016, the Ukrainian media also published information that alongside with other Russian officers, under the pretext of alleged inspection of troops at the Transnistrian territory, the general colonel of the Russian Army Aleksandr Lentsov arrived to Moldova10. He is known for participation in operations in Chechnya, Syria and the East of Ukraine. Although the details of his assignment are not clear, his appearance in Moldova is nevertheless a worrying sign.

On the other hand, Russia is pushing for the acceptance of its interests as the founding stone for the continuation of the 5+2 negotiations on the Transnistrian conflict settlement. According to the diplomatic sources, the Kremlin is considering support of a special status for Transnistria within Moldova’s borders. The respective changes in the rhetoric of Russia are believed to be a result of the efforts of the German Chairmanship at the OSCE as well as the desire of Russia to improve its relations with the EU.

However, if it is again guided by the principles of liberalism and constructivism in the bilateral relations, Ukraine will support a decision that would be acceptable for the Republic of Moldova, but in case the realist approach prevails,Ukraine is likely to be very cautious, in case concessions made by Moldova would undermine the interests of Ukraine. First, Ukraine will definitely insist on the preservation of the existing format of 5+2 talks, since the conflict in Transnistria occurred in the direct neighbourhood of Ukraine and thus its solution with the consideration of the Ukrainian interests belongs to the priorities of the Ukrainian government.

Besides, if there is a lack of trust between the governments of Ukraine and the Republic of Moldova, Ukraine may play a card of the Ukrainian minority in Transnistria and bargain with the other parties of negotiations on those issues. Therefore, it does matter if Kyiv and Chisinau work together on solving the issues emerging in the bilateral relations. If each party plays its own game, that would make the relations much more complicated and it is a task for the civil society to invigorate the governments to act in the friendly and good neighbourly manner.

Approbation of the Russian methods in Moldova

Notwithstanding the fact that Russia, and the EU likewise, did not interfere into the Moldovan domestic affairs directly, arguably the key challenge for Moldova is rooted in Russian foreign policy, specifically its “Russian World” concept (although Moldovans are not even Slavs, the heritage of Sovietization and Russification left its impact on the self-identity of many people of Moldova and Russia exploits this fact as long as there are pro-Soviet sentiments among the population of Moldova).

The Kremlin considers Moldova (alongside with Ukraine) to be an integral part of its geopolitical and cultural space, and thus invests a great deal in preserving and increasing its influence in the country. It exploits its soft power to gain control of assets and public opinion support. Russian media, which is widely common in Moldova (that’s another similarity to Ukraine), serves as an instrument for wider dissemination of the Russia’s official propaganda. Russia’s illegal annexation of the Crimea caused challenges to the inviolability of state borders, while the hybrid war tactics seen in eastern Ukraine – arguably an explicit expression of the Russian revolutionary expansionism – together with the Kremlin’s policy of promoting “controlled chaos” in the region, makes the stakes even higher for the Republic of Moldova.

Even in the unlikely case, when the EU and pro-European forces win the battle over the majority in Moldovan parliament and over the personality of the new Moldovan president, the Russian Federation will still have its leverage to interfere in order to keep the Republic of Moldova in its orbit. Russia’s Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin back in 2013 openly declared that: “Moldova’s train en route to Europe would lose its cars”.

The growing tensions between pro-Russian population and the so-called “unionists” – supporters of the reunion of Moldova with Romania, also cause vulnerability of the Republic of Moldova, and give formal justification to additional Russian interference in the domestic affairs of the republic. Therefore,

Russia will continue to question the European choice of Moldova.

The scenario that is being applied to Moldova should be perceived as an approbation of its methods. In case any of them or their combination are effective in regainingcontrol over Moldovan establishment, Russia will spread the same strategies to a wider range of countries including Ukraine – some steps in this direction are already visible in Ukraine and many further ones can be forecasted both in Ukraine and other vulnerable countries.

Regrettably, even the EU membership can hardly prevent the threat of the Russian expansionism if the membership is not accompanied with reforms in the political sphere, fighting corruption, and efficient policies in the sensitive territories with high secessionist potential. Therefore, these very fields should be the subject of close cooperation between the governments of Ukraine and Moldova and their European partners.

The exchange of information on the Russian hybrid operations, consolidated approach in counteracting Russian initiatives violating the interests of any of the countries in the region, a constructivist approach to the bilateral relations based on the common values, goals and identity can be the main tool for counterweighing challenges produced by Russia. At the same time, realism-oriented rational egoism of the countries can be counterproductive and the task for the civil society of both countries is to channel the respective messages to the governments of both countries.

To conclude with, although big players matter in international politics, bilateral relations between neighbours also remain important – in particular, when the countries have similar features and thus common solutions may be of mutual benefit. In case of Moldova and Ukraine, these relations are complicated and rotten due to the heritage of the Soviet past, unresolved issues in the borders, dangerous activities of Russia in both Ukraine and the Republic of Moldova. Furthermore, the relative failures of the political elites to deliver appropriate results in the field of reforms and European integration cause the obstacles for the European path of both countries. The leadership of both countries has the choice whether to look for solutions jointly or to approach them from a position of national egoism. Although the latter looks like the easiest way, it can create deeper divisions between Ukraine and Moldova that would be harmful for both states and that only Russia – the main troublemaker in the region – can benefit from.

The challenging task for both the political elites and civil society (in a broad sense) of both countries is to put aside their diversities and elaborate a solidarityoriented approach for the solution of existing problems. At the same time, the challenging task for the West (mainly for the United States but also for the European Union) is to keep a value-based approach prevailing over realist approaches. Otherwise, the civil society will be disappointed in Western allies and both Europe and the US may lose their traditional ally in the region.