Recently, the notion of resilience has been extensively researched and discussed in relation to information warfare, a comprehensive concept incorporating far-reaching varieties of actions, from planned and coordinated information operations in times of war and peace by a wide range of state or state-affiliated and non-state actors to sporadic actions centred on information influence, attempting to affect societal and political processes. The most recent examples of the use of such warfare include the Lisa case in Germany (2016), US presidential elections (2016), activity of Kremlin media and bots during the UK referendum (2016), and the French presidential elections (2017).

Damarad Volha, Yeliseyeu Andrei

Download results

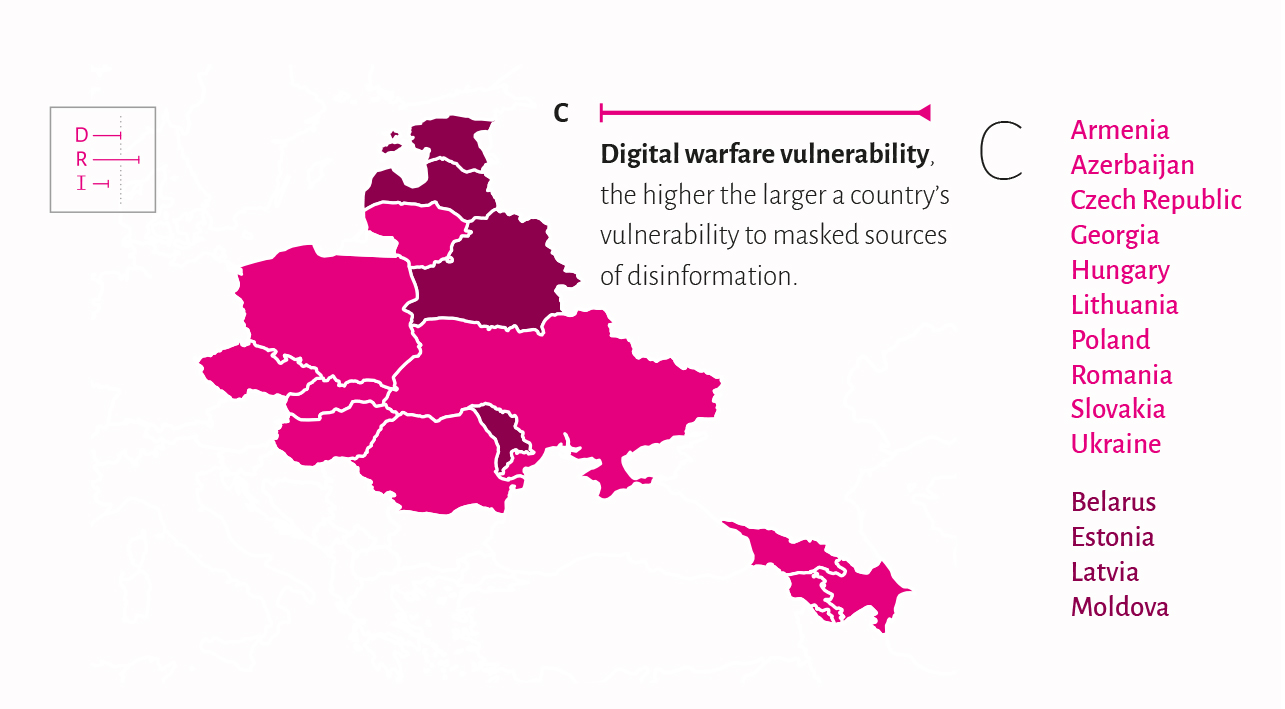

Disinformation Resilience Index

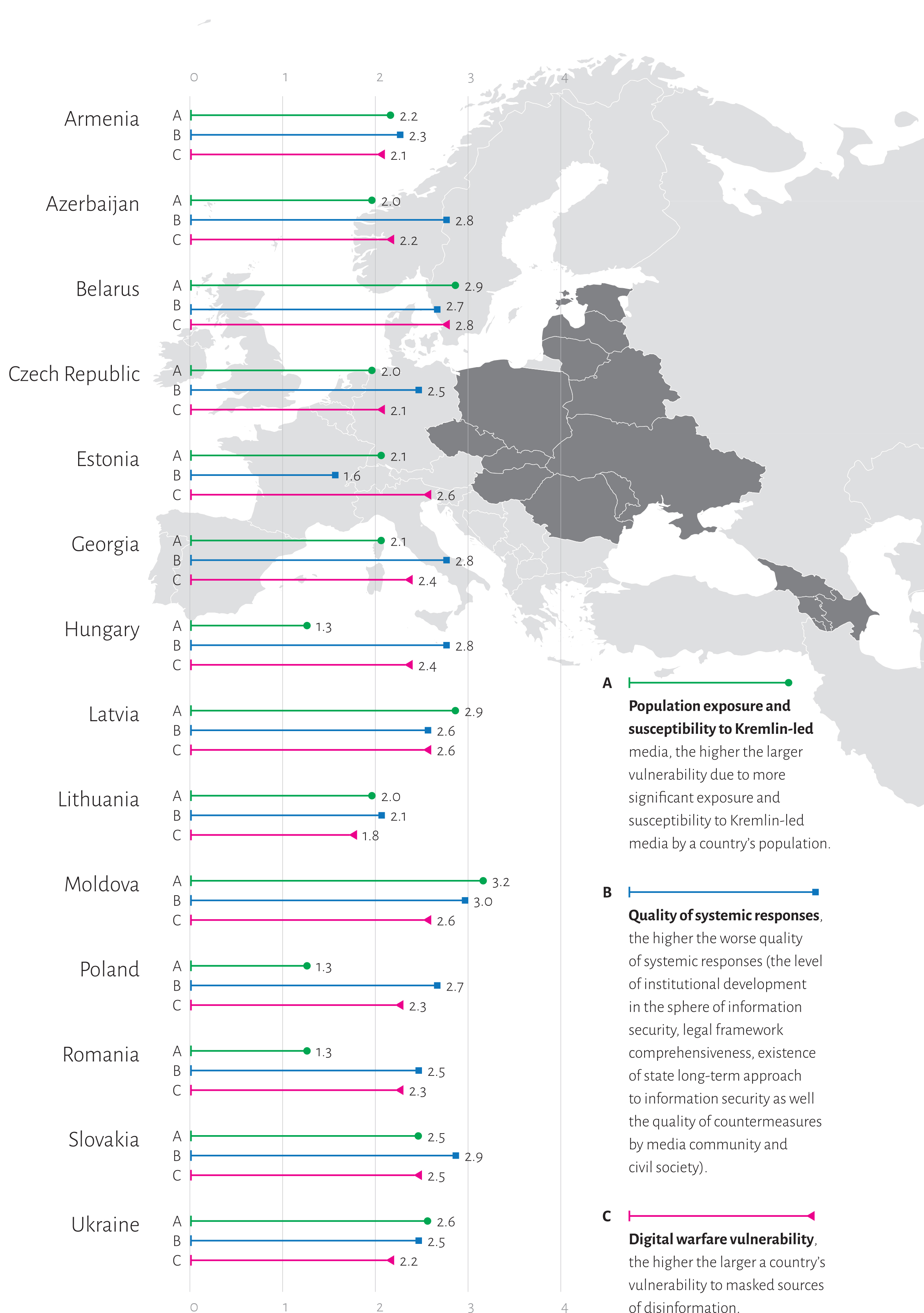

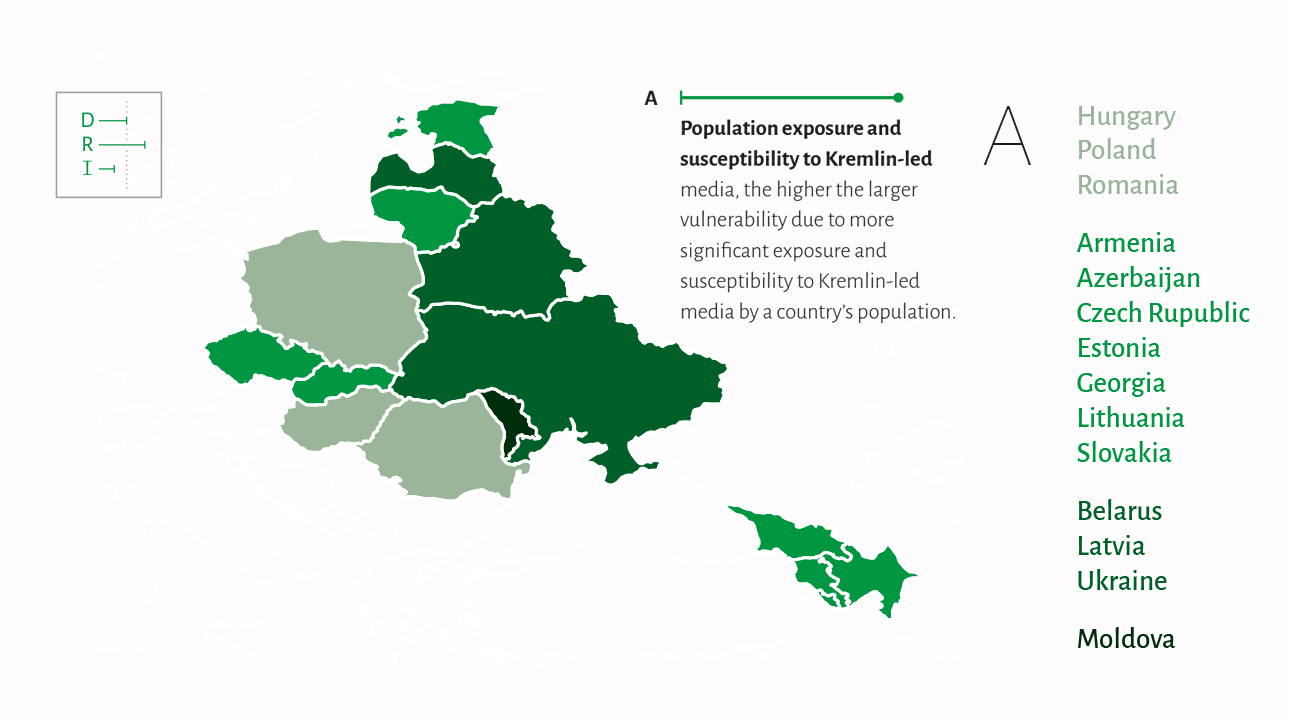

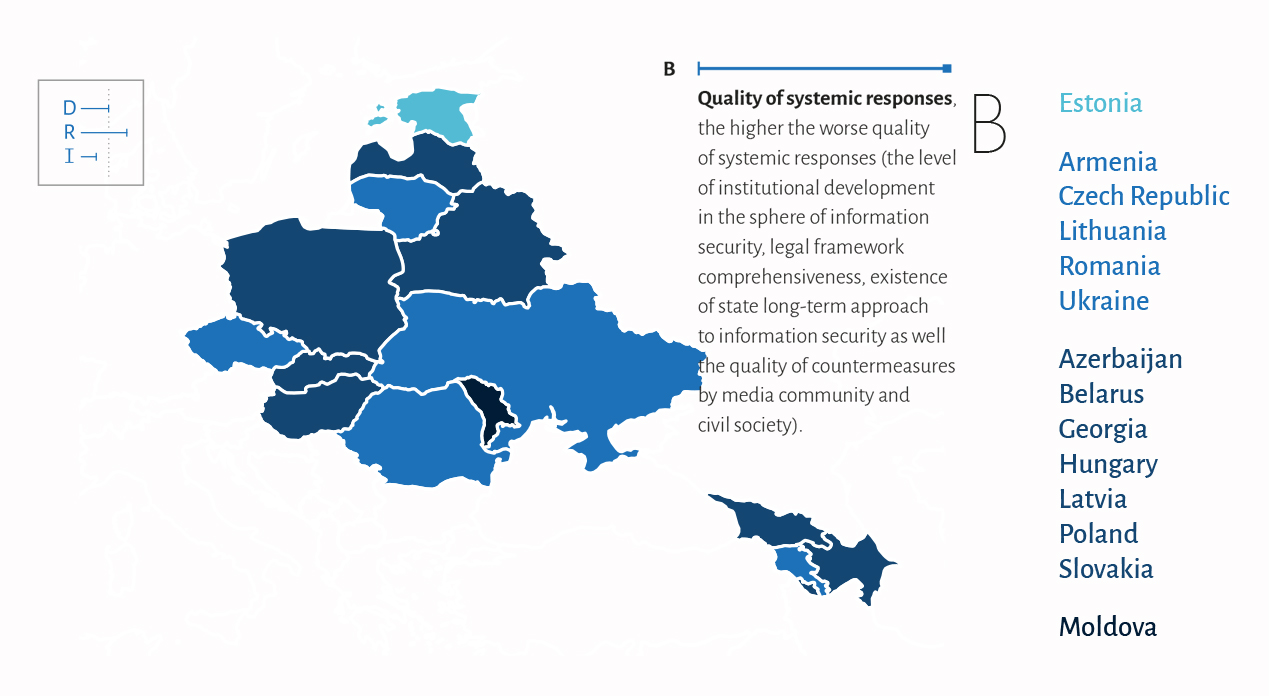

An index is a way of simplifying the complexity of the resilience phenomenon. Indeed, many components of resilience are hard to assess and an index is only a proximal representation of the actual subject of assessment. For this reason, most indices, including the Disinformation Resilience Index, only yield a relative measure rather than an absolute measure.

While consulting the Disinformation Resilience Index is instrumental for these purposes, drawing simplistic analytical or policy conclusions based on ‘big picture’ results should be avoided. Composite indicators must first be seen as a means of initiating discussion and stimulating public interest. The DRI may not explain a lot about the actual state of national vulnerability and resilience to disinformation. Instead, the respective country chapters are indispensable for a comprehensive review of vulnerable groups of the population, the specifics of the media landscape, which facilitates the spread of foreign disinformation, the respective institutions and legal regulations, and other issues related to information security.

Three composite indicators are measured on a 5-point scale from 0 to 4, the higher the worse. Each is built as a simple average of all its aggregated variables, which are treated as interval variables. Variable numerical values are the online survey response options provided by at least 20 respondents in each of the 14 CEE countries. Respondents were selected based on their substantive knowledge and professional experience. They represent government service, analytical, consulting and research institutions, media, NGOs, pressure groups, or quangos. Expert judgments ensure comparability across time. A five-point rating scale is proposed in the survey, where each variable is allotted a score of 0 to 4 depending on the answer choice, along with an “uncertain” option.

Richard Giragosian, Regional Studies Center (RSC)

Introduction

For Armenia, the onset of independence in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union came as an abrupt shock. Even prior to independence, Armenia faced the dual and daunting challenges of outright war over Nagorno-Karabakh with neighbouring Azerbaijan that erupted in February 1988, and was struggling to recover from a devastating earthquake in December 1989. While each factor tended to distort democratisation and economic development, they also significantly reinforced the country’s dependence on the Soviet Union, and then deepened its reliance on Russia. And that reliance on Moscow was also matched by a fairly entrenched pro-Russian feeling among much of the population, further driven by Armenia’s historical fear of Turkey, which was only exacerbated by Turkish support for Azerbaijan during the Karabakh war.

Despite this initial combination of pro-Russian sympathy, however, independent Armenia never had any significant Russian minority, with even a marginal presence of some 51 000 Russians in Armenia in 1989 being reduced to a mere 12 500, although even that figure includes Russian military personnel at the military base in Armenia. Therefore, in the absence of any significant Russian presence, Moscow’s policy of seeking influence in Armenia has largely centered on a reliance on ‘hard power’, defined by the Armenian insecurity from the unresolved Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. In practice, this led to the emergence of Armenia as Russia’s foothold in the region, as demonstrated by the fact that Armenia is the only country in the region to host a Russian base and to be a member of both the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) and (under Russian pressure) the Russian-dominated Eurasian Economic Union (EEU).

Despite the stereotype of Armenia as a country fully loyal if not totally subordinate to Russia, there has been a deepening crisis in Armenian-Russian relations in recent years. The foundation for the crisis is rooted in years of a steady mortgaging of the country’s national security and complicity in the Russian acquisition of key sectors of the economy by previous Armenian governments over the past two decades. Such a deepening crisis in Armenian-Russian relations suggests, however, that Moscow may be tempted to shift policy and adopt a more assertive stance toward Armenia, with a likely application of ‘soft power’ tools and disinformation techniques.

Although disinformation can only work if there is a natural and receptive audience, this is present in Armenia, as roughly 70% of the population can speak Russian. Despite this natural audience, the efficacy of Russian disinformation is not guaranteed, as knowing the language does not necessarily make the Armenian population inclined to easily accept the disinformation script. Even Russian language proficiency is a more complex factor, as less than 1% of the population speaks Russian as a first language and less than 53% of Armenians speak Russian as a second language, according to official census data. Moreover, English is more popular in Armenia, with about 40% of the population having a basic working knowledge of English. As demonstrated by the 2012 data, over 50% of Armenians favour English-language instruction in secondary schools while only 44% preferred Russian instruction.

Vulnerable groups

Armenia has neither any significant ethnic Russian minority nor any serious pro-Russian groups. Moreover, there are no pro-Russian parties or Moscow-directed politicians in Armenia. This is largely due to the Russian strategy of relying not on parties or individuals, but on leveraging pressure and influence over the Armenian government. This policy stems from the Russian control over key sectors of the economy (especially energy), the Armenian dependence on subsidised Russian gas, and the reliance on remittances from Russia for many Armenian families.

This is also reflected in the recent emergence of Russia as the country’s largest trading partner, with bilateral trade in 2017 of over 26% (1.7 billion USD), and as the primary source of remittances to Armenia. The latter factor of remittances is particularly significant, which for January-November 2017 reached 1.56 billion USD, an 18% increase from the same period in 2016, and accounts for roughly 15% of Armenian Gross Domestic Product (GDP), with over 60% of total remittances coming from the approximately 125 000 Armenians working in Russia.

Nevertheless, aside from the economic leverage, in terms of the paucity of vulnerable groups in Armenia, Russia has limited capacity for implementing effective disinformation campaigns. For example, the Armenian Apostolic Church has vehemently prevented past attempts of influence by the Russian Orthodox Church and remains independent.

A second limiting factor stems from the influence of the (largely Western) Armenian diaspora and the strong sense of Armenian nationalism. The separation and marginalisation of isolated pro-Russian groups (cultural foundations and dubious NGOs) has also created a vicious circle for Moscow. The lack of direct Russian patronage has left these groups small, fragmented, and divided, but their very weakness and marginalisation has discouraged Moscow from more actively financing or supporting them in any significant way.

Nevertheless, in the event of any possible change in Moscow’s approach, there is still potential for reverting to Russian soft-power influence and pressure within Armenia. And there are both willing and unwitting individual political figures that may welcome such Russian backing and support. In this context, the past experience of defending the Armenian president’s decision to join the EEU has revealed that a few pro-Russian groups and some marginal organisations were utilised in a subtle Russian disinformation campaign aimed to promote the EEU in Armenia and by downplaying the costs of abandoning the Association Agreement with the EU. As one noted analyst observed,

‘the EU should make greater efforts to communicate the benefits of cooperation with the EU as widely as possible to the Armenian people, in part to counter Russian-led disinformation campaigns, citing these groups, and including the Integration and Development or Eurasian Expert Club’.

Although these groups were eager to curry favor with the Armenian government and were able to play a supportive role coinciding with the defensive reaction by the Armenian government, which was eager to defend its decision, this was a temporary ‘marriage of convenience’ and these groups remain marginal and isolated within Armenia. Another potentially important element of leverage for use in any future Russian disinformation campaign is the threat perception rooted in the last several years of ‘netwar’ and cyberattacks between Azerbaijan and Armenia. Yet, even on its own, according to a prominent expert,

‘the information war between Armenia and Azerbaijan is going to continue. Both sides acknowledge that information is becoming more influential in the context of modern armed conflicts. This suggests that more substantial means and measures, as well as professionals and specialists, are going to be involved. It is already obvious that not only propaganda but also cyberattacks and hacking operations are going to play larger roles’.

And although neither side has an ‘official cyber army’, the expert warns that:

‘nevertheless, the increase both in the quantity and quality of cyberattacks and intrusions already attests to the fact that both sides are preparing for an even greater cyber war’.

Media landscape

In order for any disinformation campaign to be effective, there needs to be at least a minimum degree of receptivity, with a natural ‘audience’ capable of being influenced. In the case of Armenia, for example, one ‘lesson learned’ from the 2015 surprise decision by President Serge Sarkisian to sacrifice the Association Agreement with the EU was the clear lack of any effective communications strategy. In that case, the population generally was unaware and not very well informed of the concrete benefits of the Association Agreement. Additionally, practical advantages for the ordinary consumer and citizen from such an alignment with the EU were never articulated until an information campaign undertaken by the Armenian government in defence of its about-face, with inspiration if not support from Russia. This transformed the lack of information into disinformation, even distorting the fundamental EU values into an ‘attack on traditional Armenian values’.

More recent assessments of public opinion in Armenia have found the reverse, and confirmed an increase in positive perceptions of the EU. For example, according to the ‘2017 Annual Survey of Perceptions of the European Union, Public Opinion in Armenia’, an overall positive perception of the EU increased from 44% in 2016 to 48% in 2017. There was also a dramatic fall in negative responses, from 13% to 5% in the same period. A clear majority also held positive perceptions of the EU in terms of human rights, freedoms, and civil liberties, and a high level of trust. Against that backdrop, however, the long-term sustainability of such positive perceptions also depends on measures capable of countering and combating future disinformation campaigns that will rely on a compliant or at least conducive closed media landscape.

For the overwhelming majority of Armenians, television remains the dominant source of news. With two main public television networks and Russian channels widely available, there is a near total lack of objective news coverage, especially in terms of domestic politics and international affairs. This is directly attributable to the fact that the main Armenian state channels are solidly pro-government in their coverage and editorial position, with a total absence of any neutral or opposition television stations and due to the much weaker influence from the country’s 25 private stations, which have much more limited reach, as their signals do not reach national audience.

The two main public networks (H1 and Ararat), as well as the private, but generally government-subservient Armenia TV and Shant networks, have a combined reach and penetration of more than 85% nationally. There are also five Russian channels, two of which (Channel One Russia and RTR) have full retransmission rights throughout territory of Armenia, while the other three (RTR-Planeta, Kultura, and Mir) are limited to the capital Yerevan. In addition, ownership of the main TV networks is also a problem, as the leading networks beyond the two state-affiliated public stations are either directly linked or owned outright by government-connected individuals or pro-government political parties. For example, as the Open Society Foundation (OSF)-Armenia found in an October 2017 assessment,

‘media ownership is still not transparent; the law does not require disclosing media ownership. The main shareholders of television companies are either representatives of political elites or large businesses, which leads to full control of broadcast media. The broadcast legislation does not guarantee independence of the national regulator’.

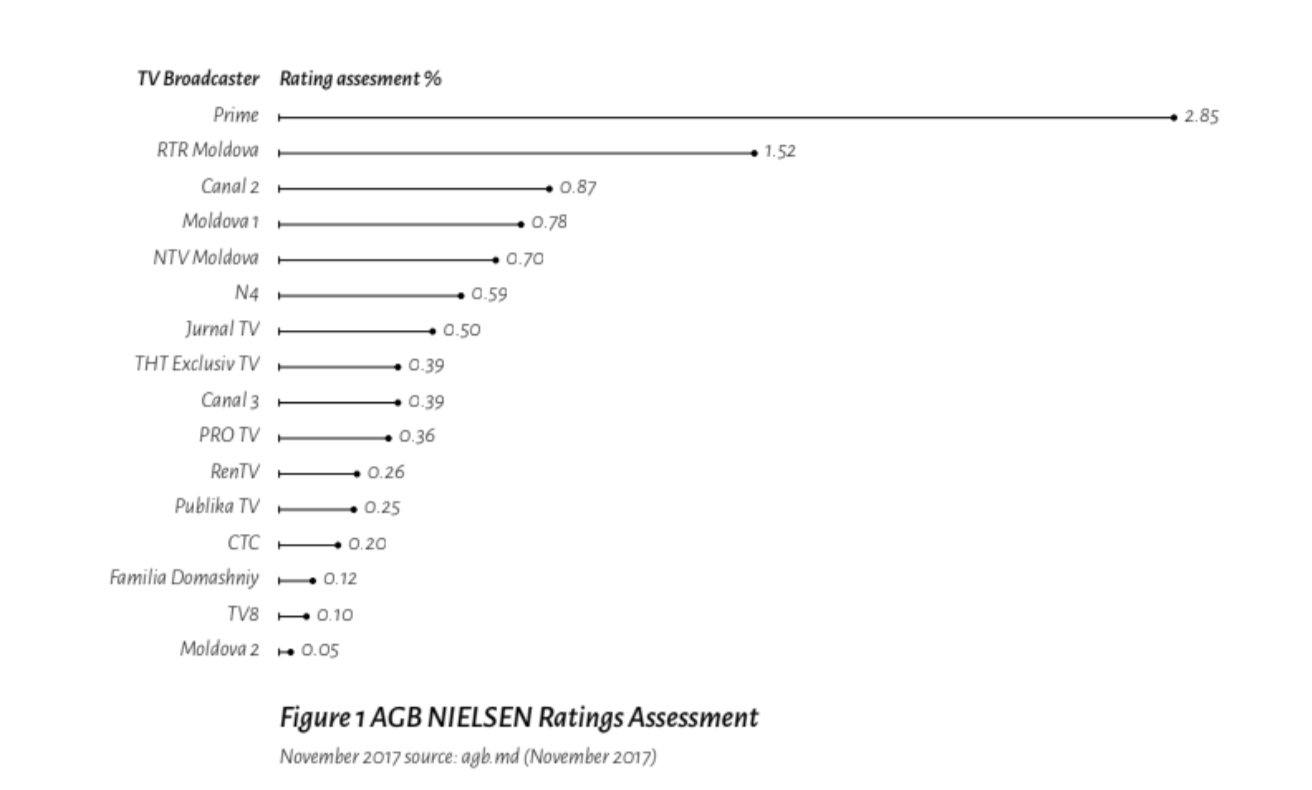

In terms of popularity, as measured in Yerevan by AGB Nielsen Media ratings, the top ten most popular TV stations, ranked in descending order, are: Armenian Public TV (H 1), Shant TV, Armenia TV, H2 TV (second public broadcaster), ‘Dar 21’ TV, Yerkir Media TV, Kentron TV, Arm News (Euro News), ATV, and Yerevan TV. Most significantly, each of the top ten TV stations are Armenian, with no foreign, or Russian, TV stations listed. This may be at least partially explained by the fact that Russian TV and Russian-language programming is only available in Armenia for cable and satellite TV users, with no presence on regular (free) digital TV.

Moreover, according to the respected ‘Caucasus Barometer’ public opinion survey conducted in October 2017, despite access to the Russian RTR Planeta and Russian 1st/ORT stations, to which 84% and 75%, respectively, of respondents indicated that they had access, only 38% stated they regularly watch Russian 1st/ORT and 37% said that they watched RTR Planeta on a regular basis. The same survey found higher numbers for respondents indicating that they use Russian TV channels as a daily source of news, but with 51% stating that Russian TV was their source for daily news and current events compared to 87% of respondents saying the same for Armenian TV channels.

Far behind television, but the second source of news and information, is radio, which has widespread reach. There are six Russian-language radio stations, ranging from re-broadcasters of Russian stations, such as Russkoye Radio. There is also a small, but growing audience for the Russian-language Radio Sputnik (with content tailored to Armenia, including local reporting), as well as for music in Russian from Auto Radio FM 89.7 and programmes on Kavkaz FM/Кавказ ФМ.

Russian-language radio is neither very popular nor widespread in Armenia. Instead, for news and information, the most popular radio outlets by far are local Armenian programmes and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s (RFE/RL) Armenian service. The latter broadcasts on air for over 20 hours a week and reaches much of the country as a result of re-broadcasting arrangements with local and regional radio stations. Additionally, French-language programming on Radio France Internationale (RFI) has also been growing in popularity, but is limited to Yerevan.

In terms of newspapers, public consumption has been steadily declining, as reflected by low circulation (with about 2,000-3,000 daily copies the average), and they are not available outside the capital Yerevan and the major cities. Newspapers are further constrained by financial vulnerability, with little advertising revenue and occasional state pressure on prospective advertisers during election campaigns. Due to the lack of audience and limited influence of the country’s print media, there is an ironic degree of press freedom, although a more dangerous trend of violence against journalists has been a serious concern for several years. This in turn has fostered an environment of fear and intimidation, leading to some cases of journalistic self-censorship. There is also a widespread perception that professional conduct and journalistic capacity are seriously under-developed throughout much of Armenian media, which is also matched by a documented degree of mistrust and a lack of reliability in much of the media’s coverage and news reporting.

There is a significant degree of freedom regarding the internet as a source for news and information, with matching popularity of electronic news agencies and sites. Internet access in Armenia continues to grow and as of 2017 there are an estimated two million or more Armenians online. This accounts for over 73% of the population. Social media are also popular and relatively free from restraint, with many users accessing social media and the internet via mobile devices. In fact, although national internet penetration from home or office computers is only about 62%, the availability of mobile phone internet access has contributed to a dramatic expansion of users, with the mobile 3G service widely available, covering 90% of the country.

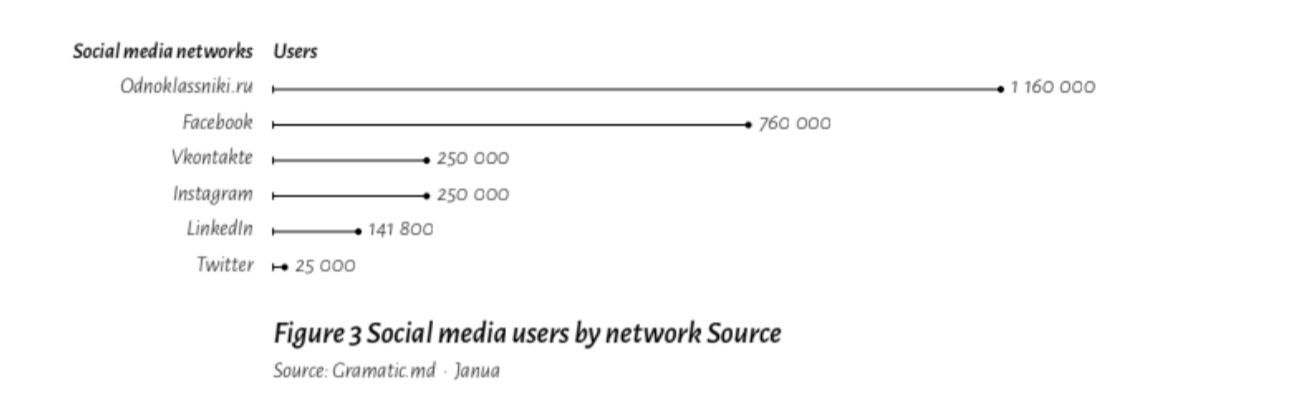

While the Russian-language Odnoklassniki platform is widely used, Facebook is one of the most popular social media platforms for news and commentary, and Twitter is not yet a serious factor in Armenia. Overall, the option to freely launch an online publication without a license and with largely basic regulatory requirements has also fostered limited state control or pressure. This has encouraged the startup of many independent online media outlets in Armenia.

Originally a radio station, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s (RFE/RL) Armenian Service, made impressive gains in the areas of internet-based TV and video news coverage. This further expanded its influence and popularity in the Armenian media sector beyond radio transmission, and website-based news and commentary. As the only objective news source with online video coverage, RFE/RL also stands out for its impressive live coverage. This live coverage goes beyond traditional elections or events, such as the July 2016 hostage crisis at a police station in Yerevan. For RFE/RL’s Armenian service, the audience has grown dramatically. Since 2016, it has seen a record number of website visitors (5,633,588), YouTube views (18 million), and Facebook users (17.7 million views). Such efforts have been followed by others, including the smaller CivilNet (https://www.civilnet.am), etc.

An interesting observation of the Armenian media landscape by Manana Aslamazyan, the head of ‘Alternative Resources in Media’, argued that,

‘for Armenia, the problem of the quality (of TV media) is aggravated here by some other elements’,

including that,

‘the number of media outlets in Armenia exceeds its needs and possibilities from the point of view of the content’.

In this context, she stressed that,

‘young journalists are not motivated to improve the quality of their work as they realize they won’t be paid more. And as far as these media don’t possess much money and have a small staff, they have to manage to do a lot of things during the day, and this is one of the reasons for the low quality of their work: the journalists are running from one news conference to another, hurry to their offices, they write with mistakes, which are later copied by many other websites. On the whole, today, Armenian journalism is based on news from press conferences without personal analysis, without attempts to gather various opinions, tell the story from various viewpoints. There are a few serious columns and analytical articles’.

Aslamazyan went on to add,

‘the second serious problem affecting media quality is responsibility. Today, the opposition media outlets in Armenia use the term ‘responsible media’ only in a negative context, which can be justified to some extent. Though, you know very well that the term ‘responsible reporting’ is widespread in the West and is one of the basics of good journalism. Generally speaking, one edition may write tomorrow that during our interview you got mad and left, slamming the door, and if no one refutes it, the author of that ‘item’ will remain in full confidence that next time he can get away with it. There is an atmosphere when journalists sinisterly believe they have the right to lie. On the other hand, there are debates in Armenia over the law on defamation, which seems to fail to resolve the problem either’.

It is clear that in countries with closed or limited media freedoms, there is a related tendency for ‘conspiracy theories’ or other cases of unreliable information and rumours. In such cases, the impact of disinformation can be especially serious, as the lack of reliable information only promotes misinformation and disinformation. For Armenia, this is a problem, as demonstrated in Freedom House’s recent report, ‘Freedom on the Net 2017’. This report found that, ‘Internet freedom declined in Armenia after users experienced temporary restrictions on Facebook while online manipulation increased in the lead-up to parliamentary elections’.

Beyond the impact on internet freedom, this survey also revealed Armenia’s relative cyber insecurity, exposing the vulnerabilities to both internal interference and external manipulation. In the case of ‘temporary restrictions on Facebook’, the Armenian authorities were suspected of interfering with the social media platform. This made it ‘unavailable for almost an hour on several ISPs during protests’ related to the two-week hostage situation in Yerevan in July 2016. This is significant, not in terms of the duration of the outage or even in the fact of the interference, rather, this is the first demonstrated display by the Armenian authorities of the capacity to intervene and interfere with Facebook users within Armenia. Unlike an earlier, and much more crude or primitive episode in 2008, when the authorities were able to block online content.

A deeper and related problem is media freedom and the vulnerability that stems from a lack of public trust or confidence. In October 2017, the well-regarded ‘Caucasus Barometer’ public opinion survey aimed to gauge TV news as a source of information and in terms of ‘informing the population.’ This survey indicated that 39% of respondents stated that TV does a very poor or quite poor job while only 13% said they did quite well or a very good job. Additionally, in terms of ‘trust in the media’, overall it revealed that another 39% of respondents either fully distrust or rather distrust the media, with only 23% indicating that they fully trust or rather trust the media.

In Focus

Russia Picks Fight with Armenia over Nazi Collaboration

Armenians responded with a vigorous defence that mostly glossed over the liberation hero’s alliance with the Third Reich.

A historical dispute between Armenia and Russia over Armenia’s liberation-hero-turned-Nazi-collaborator has reignited, injecting tendentious World War II politics into the two allies’ uneasy relationship.

A senior Russian lawmaker wrote a piece in the newspaper Nezavisimaya Gazeta, published on February 6, 2018, headlined ‘The Return of Nazism from the Baltics to Armenia’. The theme is not a new one for Russia, which in recent years has made great efforts to delegitimise nationalist fighters who collaborated with Germany in World War II in the cause of liberating their countries from Soviet rule.

But while that has become an old story in the Baltics and Ukraine, it’s a new one in Armenia. Armenia, unlike those other states, is a close ally of Russia and until recently has been spared criticism for its heroes’ dabbling in Nazi collaboration.

That may now be changing. ‘Armenia, a strategic ally of Russia, has erected a monument in the center of Yerevan to the Third Reich collaborationist Garegin Nzhdeh’, the lawmaker, Lyudmila Kozlova, wrote. Nzhdeh, she wrote, ‘has the blood of thousands of our grandfathers and great grandfathers on his hands’. That followed an event in January in Russia’s Duma, in a roundtable discussion on ‘The Fight Against Valorisation of Nazism and the Return of Neo-Nazism: Legislative Aspects’, at which the participants called on Armenia to take down the statue of Nzhdeh, which was put up in 2016.

These salvoes reopened a battle that appeared to have resulted in a ceasefire last year, when a Russian military television station aired a programme making many of the same allegations against Nzhdeh. After Armenia vociferously complained that time, Russia quickly backed down, removed the programme from the TV station’s website and issued an apology. This time, though, the accusations are coming from higher up in the power structure, and Russia has not apologised.

Legal Regulation

Officially, Armenia has constitutional guarantees of freedom of speech and of the press. Legally, the constitution also guarantees that the ‘freedom of mass media and other means of mass information shall be guaranteed’ and that ‘the state shall guarantee the existence and activities of an independent and public radio and television service’. The constitution also extends guarantees that prohibit ‘incitement to national, racial, and religious hatred, propaganda of violence’. Yet as with the shortcomings of the country’s judicial system there is a serious gap between the legal and constitutional guarantees, and their fair and compete application.

The real vulnerability for Armenia, in terms of disinformation campaigns, stems from the fundamental lack of policy awareness and institutional preparedness. For example, despite gains in both legislation and regulatory, as well as monitoring of money laundering and cybercrime, there are serious deficiencies in other key areas. This includes data protection and the safeguarding of critical infrastructure from cyber-assault. Moreover, despite progress in developing and passing new legislation in the field of information security over the past decade, the absence of any clear understanding of the difference between information security and cybersecurity remains a basic and lingering impediment. Even more of an obstacle for a more robust defence against cyberattack and intrusion is the inactivity of relevant state bodies and entities. For example, an interdepartmental working group on information security that was established has neither sufficient resources nor the policy influence that it requires.

Similar to such inactivity, where the interagency body rarely meets, the Armenian National Security Council (NSC) is a marginal and ineffective body. This lack of institutionalised national security can be rooted in the infrequency of NSC meetings, although there has been a marked increase in the role of parliamentary committees with jurisdiction over defence and security policy in recent years. However, the sheer dominance of the executive branch in general, and the defence minister in particular, over all aspects of security has only meant that the dysfunctional nature of the national security process remains uncorrected. The first problem is structural. The Armenian NSC is rarely convened as a full consultative body, and even when it convenes, the deliberations are largely focused on the implementation of a decision already made.

Overall, despite some gains in the legal framework and regulatory oversight, Armenia is generally far behind other countries in the field of cybersecurity. According to the Global Cybersecurity Index 2017, Armenia is ranked only 111th out of 165 nations in a global index that measures the commitment of nations across the world to cybersecurity. That ranking placed Armenia as the second-worst performing country in terms of cybersecurity throughout the former Soviet Union, ranked only above Turkmenistan. This also places the country behind all of its neighbours (Georgia is ranked 8th and Azerbaijan is 48th) despite the seemingly obvious motivation from ‘the hype about Armenia’s booming IT industry, as well as constant threats from Azerbaijani hackers’.

However, Armenian officials routinely argue that the country is committed to cybersecurity, as demonstrated by its National Security Strategy. The strategy includes such platitudes as ‘ensuring the reliability, security and safety of communication infrastructure’, but reflects no specific recognition of either the nature of evolving cyberthreats nor the necessity to safeguard critical infrastructure and networks from cyberattack. Thus, the 18-page National Security Strategy is largely a missed opportunity for presenting a guiding framework for security in a difficult and dynamic new threat environment, further reflected in the fact that the strategy has not been updated or modified since its adoption in January 2007.

Beyond the National Security Strategy, there was a more focused attempt to address cybersecurity through the formulation of the country’s ‘Information Security Concept’. This attempt, through the development of Armenia’s ‘Concept of Information Security’ in June 2009, reflected an emphasis on the formal recognition that,

‘the national security of the Republic of Armenia depends considerably on information security, which encompasses components such as information, communication, and telecommunication systems. The concept also includes a general assessment of the problems of information security of the Republic of Armenia, current challenges and threats, and their root causes and peculiarities, as well as methods to address them in different spheres of public life’.

Yet this too was a flawed document and has been criticized by observers, including a recognized expert, Albert Nerzetyan, who has recently argued that the concept is

‘a rather lengthy document, with no clear assignment of duties and responsibilities. More importantly, it was a copy-paste of Russia’s 2000 ‘Information Security Doctrine’ ’.

The implementation of the concept was reliant on the formation of an intergovernmental committee that was created to coordinate all programmes related to the concept of information security. In causation, the effort quickly stalled, similar to the National Security Council, due to its flaws in a lack of authority, absence of activity, and infrequent and inconclusive meetings. The Armenian government also sought to address the issue by developing a ‘concept’ on the ‘Formation of Cyber Society’, which was approved in February 2010. The adoption of the concept also ordered the formation of a new ‘Council of Electronic Governance,’ to be tasked with carrying out activities for ensuring the cybersecurity of the state through yet another state committee and a group of experts.

More recently, there have been some achievements, mainly due to the initiative of the Armenian National Defence Research University. In this instance, the University worked on a new and more innovative ‘National Cybersecurity Strategy’ in close cooperation with the U.S. National Defense University (NDU) and Harvard University, with a final version completed in 2017. Also in 2017, the Armenian National Security Council adopted the ‘Information Security and Information Policy Concept’, whose provisions envision the development of a national strategy (including specified roles, responsibilities, etc.)’.

Although criminal liability for defamation was eliminated in 2010, the civil code of Armenia imposes high monetary penalties of up to 2,000 times the minimum salary. Additional criticism centres on the 2010 ‘Law on Television and Radio’, which was negatively assessed for failing to promote media pluralism in the digital age. Its shortcomings included ‘a limit to the number of broadcast channels; a lack of clear rules for the licensing of satellite, mobile telephone and online broadcasting; the placement of all forms of broadcasting under a regime of licensing or permission by the Regulator; the granting of authority to the courts to terminate broadcast licenses based on provisions in the law that contain undue limitations on freedom of the media; and a lack of procedures and terms for the establishment of private digital channels’.

For the country’s broadcast media, there is a legal and regulatory requirement of state-issued licenses from the National Commission on Television and Radio (NCTR). This has been widely seen as an obstacle to media freedom and diversity. Additionally, the NCTR is discredited by several cases of state interference and pressure over licensing, although print and online media are exempt from licenses. The two most glaring cases involved the independent Gyumri-based GALA TV and the opposition A1+ TV station, which in 2002 and 2015 were forced off the air after their licenses were revoked or not approved. A1+, however, was able to forge a unique agreement for broadcasting some limited hours of programming with the ArmNews broadcaster, supplemented by online video coverage.

Furthermore, in 2010, the Armenian government passed a set of controversial amendments to the Armenian law on broadcasting that enabled the government regulators to grant or revoke licenses with little or no explanation, and to impose programming restrictions that would confine some stations to narrow themes. This included culture, education, and sports.

Institutional setup

Armenia’s Public Services Regulatory Commission (PSRC) is an independent regulatory authority whose legal and regulatory jurisdiction over the telecommunications sector is derived from the 2006 ‘Law on Electronic Communication’ (revised and updated in 2014), and supplemented by the 2003 ‘Law on State Commission for the Regulation of Public Services’. Despite the possibility of concern over the presidentially appointed nature of the PSRC commissioners, most independent evaluations have found that the commission’s performance in overseeing the telecommunications sector,

‘are transparent and have generally been perceived as fair’.

In terms of combating cases of disinformation, there are few effective institutional safeguards in Armenia. This is because of the absence of any consistent evidence of cases of disinformation, as the lack of any effective Russian soft power in Armenia to date and Moscow’s preference to pressure a submissive Armenian government rather than to invest directly in politics or to back individual parties or politicians. Also, there is a structural vulnerability in the face of future disinformation campaigns. But, the transformation to a new parliamentary form of government in Armenia has created a unique opportunity for initiatives related to parliamentary oversight and safeguarding against disinformation.

Digital debunking teams

The Media Initiatives Center (MIC), which has been working in the media sector of Armenia for more than 20 years, supports the freedom of expression and the development of independent media. MIC is involved in the improvement of media legislation and the protection of journalists’ rights, and aims to support current and future journalists to develop their skills in information verification and fact-checking by promoting more accurate information dissemination. Most notably, it has implemented the project ‘Debunking Disinformation’.

The main component of the project is the International School of Information Verification. A project that includes international experts and is organised for 16 participants from Armenia and Georgia who are presented with best practices, learn to apply different tools and methods for information verification, and produce journalistic material. In parallel, the MIC staff also work with several Armenian universities helping professors to develop and implement new modules of information verification during the teaching process.

A second related effort is carried out by Sut.am, which is an independent fact-checking media founded by the ‘Union of Informed Citizens’, a consulting NGO. This group, whose project is an independent effort that does not represent the interests of any political party or other group, specifically seeks to prevent the spread of obvious disinformation.

In Focus

Disinformation on Twitter before elections

In April 2017, a series of Russian-linked moves that seemingly sought to influence the coverage of the Armenian parliamentary election were seen as a coordinated campaign of outright disinformation. This case was different, however, as it involved external interference in real-time coverage of the elections, ‘possibly automated accounts spread misinformation’ about the vote via Twitter and ‘independent media accounts’ were hacked or disabled. This was especially egregious at the onset of the Armenian elections when, ‘beginning two days prior to the vote and escalating through election day itself, a steady stream of disinformation and trolls by Russian-based and Russian-language Twitter and Facebook accounts besieged coverage and commentary of the election on the internet.’

This flurry of electronic disinformation was largely focused on the dissemination of a fraudulent and crudely faked ‘letter’ purporting to be an official document from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) instructing voters to elect the opposition in Armenia.

That email document was immediately refuted by the U.S. Embassy in Yerevan, which pointed out grammatical and spelling mistakes in the text and stressed that any genuine USAID email would not be sent from a private Gmail account.

And as quick and effective refutation, the U.S. Embassy’s response also reiterated the need for such vigilance by the Armenian authorities. As media reports noted at the time, ‘although the text accompanying the image varied, at least 43 accounts that shared the image used ‘НПО готовятся сорвать выборы в Армении’, which translates to ‘NGOs prepare to disrupt elections in Armenia’. And the accounts were also found to have a number of features which gave them the appearance of a network of automated ‘bot’ accounts, rather than genuine users, with one featuring an avatar image copied from a stock online photo of actress Barbara Mori’. And in addition, the original fake USAID post was shared by a set of Russian accounts. As the Armenian media and analytical community learned, this is unlikely to be the last such exercise in Russian disinformation targeting Armenia.

A second, related development occurred less than 12 hours before the start of voting, when several leading independent Armenia Twitter accounts that serve as regular sources of objective news and information were suspiciously ‘suspended’. After a strong protest was lodged with Twitter, the accounts were re-activated in the early morning hours. Most notably, the affected Twitter accounts included analyst Stepan Grigorian (@StepanGrig), the CivilNet online news portal (@CivilNetTV), the Hetq online news agency (@Hetq_Trace), and independent journalist Gegham Vardanyan (@Reporteram)’.

Media literacy projects

There have been some small and fairly sporadic media literacy projects in the recent past. The most significant effort was undertaken by MIC. This effort was ‘aimed at developing and deepening the concept of media education development in Armenia with a view of clarifying the steps and further actions directed towards the increase of the level of media literacy jointly with the state authorities, schools, higher education institutions, training centers, media, and other interested stakeholders’. It also includes a series of workshops and specifically targets the broader need for ‘public education’, consisting of training for teachers, the development of a manual and related computer game for classroom use, and collaborating with media, libraries, and other relevant groups.

Conclusions

Despite the limitations and impediments to Russian disinformation and the application of ‘soft power’ in Armenia, there are some worrisome developments of note. What we have seen, moreover, is a steady yet subtle increase in the application of Russian ‘soft power’ in Armenia. An increase driven by efforts to promote the Russian language (as an official second language), the proposed renaming of streets, and erection of monuments glorifying the Soviet past, and defined by a more effective assault on ‘European values’ that argues that Russian ‘family values’ are closer to the (more conservative) traditional Armenian culture than the alien ‘European values’ (even arguing there is a threat from same-sex marriage, LGBT rights, and other elements to the Church and to the Armenian family unit). Although this effort has largely failed, it is again seen in the recent debate over the government-backed legislation deepening the criminalisation of domestic abuse.

Beyond the limited returns of these efforts to leverage Russian soft power, there has also been a more active economic-centred effort to maximise Russian capital and investment. This activity is aimed at both strengthening the prime minister personally and bolstering the Russian image politically in Armenia. Yet, this has still been only marginally effective, as real investment has continued to be significantly less than promised or expected, and has been limited in the face of the harsh reality of declining remittances from Russia and the loss of jobs for many Armenian labourers in the Russian construction sector. Moreover, the so-called ‘Russian investment club’, a pilot project of the prime minister as an attempt to channel ethnic Armenian capital from Russia into several flagship projects in Armenia, has also been damaged by media reports exposing criminal links and dubious backgrounds of so-called ‘businessmen’.

Yet most distressing, as a crisis or at a least a problem in Armenian-Russian relations only continues to fester. Moscow may be tempted to adopt a more assertive stance toward Armenia, with a likely application of ‘soft power’ tools and disinformation techniques. And in that case, Moscow lacks a dependable and natural partner on the ground. But Armenia’s vulnerability, and the absence of either effective safeguards or a robust response to earlier attempts at Russian disinformation, will only continue to limit and weaken efforts at forging real resiliency in Armenia.

Recommendations

It is fairly clear that with the crisis in Armenian-Russian relations, the possibility of a new Russian campaign of disinformation and a related investment in Russian ‘soft power’ may be a logical, and expected response by Moscow. In light of such a scenario, and despite the natural partners and instruments for Moscow to use in Armenia, the country’s vulnerability and absence of effective safeguards against disinformation will undermine attempts at forging resiliency.

Therefore, the following recommendations are essential:

First, a move towards a new and unprecedented parliamentary form of government. Parliament should assume oversight responsibilities to enforce measures aimed at combating especially negative aspects of disinformation, including hate speech, but also broaden it to cover bias and subjective ‘fake news’ reporting.

A second measure would be a more comprehensive but legally sound monitoring of Russian media outlets in Armenia. A measure that includes the capacity to impose punitive moves when and if the coverage was found to be an example of disinformation.

And legislatively, a third recommendation would be for a fresh review of problems with prior legislation, such as the laws on mass media and on the freedom of information, which are each plagued by poor enforcement and implementation, and for a strengthened defence of reining in the inordinate regulation on ‘new media’ (electronic media especially). This is important because a more even ‘playing field’ for an open and transparent media environment is one of the more basic defences against disinformation.

Additional measures are also necessary for the Armenian parliament, which highlight the imperativeness of legislative changes to the following areas:

Regarding the transition to digital broadcasting:

- Offering a financial assistance package for needy families to afford the transition to digital TV.

- A comprehensive information campaign explaining the new standards and parameters for digital broadcasting in Armenia.

Regarding broadcasting regulators:

- Introducing and safeguarding a higher level of independence of members of regulatory bodies.

- Reduction of licensing procedures to decisions of purely technical or commercial character.

- Armenia’s sole independent regulatory authority for telecommunications, the Public Services Regulatory Commission (PSRC), is in need of reform in two key areas: with an absence of term limits, the presidentially appointed PSRC commissioners enjoy unchallenged authority and can only be dismissed in unusual or difficult-to-document cases of crime or blatant incompetence.

Defence of intellectual property (copyright):

- Implementation of corporate mechanisms for action.

- Even before these mechanisms begin, intensive practical application of updated legislation, including the harmonisation of intellectual property protection principles and the rights of citizens to obtain information.

Improving the protection of civil rights in conjunction with the guarantees of freedom of expression:

- The introduction of the concept of moral damage compensation in cases involving libel or slander, privacy protection, the safeguarding of sources and whistleblowers, and the presumption of innocence.

- Promoting methods of solving information disputes through media self-regulation bodies and arbitration in Armenia.

General reforms in existing media legislation:

- The progressive liberalisation of legislation, approximation of the principles governing the media industry to those areas of economic activity that do not require special regulation.

- Harmonisation of communication and media legislation to make the regulation of traditional and new media more uniform and fair.

Develop media as a business model:

- The formation of industrial committees, with regular consultations with representatives of the media industry, to discuss the situation on the basis of objective data and research.

- The creation of funds (both by government, donors, and alternative means) designated for the ordering (through tenders) of media production important to the public. Aimed at creating competition in this field for the Public Broadcaster of Armenia, both to ensure quality consumer demand and to overcome the monopoly of PTRC on government orders.

- Increase the depth of media measurement methodology with the prospect of targeting advertisements, while promoting the fragmentation and segmentation of the advertising market, using progressive technologies of measuring the audience of the new media, and the implementation of special trainings for the introduction of modern methods of attractive advertising.

Victoria Bittner, Center for Economic and Social Development

Introduction

The geopolitical location of Azerbaijan, the only route for the Caspian oil and gas resources to reach the world markets avoiding both Russia and Iran, makes it an alluring destination for Kremlin-inspired propaganda. This is because the Kremlin tries to monopolise all energy and transit routes to and from Europe, hence making it essential to hold an advantage over Azerbaijan.

Azerbaijan used to be a central piece of the Soviet Union’s Middle East policy. Its shared borders with both Iran and Turkey, the large number of the Azerbaijanis living in Iran (where they are the second largest ethnic group after the Persians), and historical and linguistic ties with Turkey were all vital for the Soviet decision-makers.

During the Second World War, the Red Army was stationed in northern Iran, in the area inhabited by the Azerbaijanis. At some stages of history, including modern times, Azerbaijani elements were used against both Iran and Turkey. Russia used a variety of means to maintain its influence.

In the 1990s, Russia tried to keep Azerbaijan from joining the Western economic and political projects. At that time, Azerbaijan tried to attract some foreign investments in the region, and to build platforms for cooperation with the EU countries and the United States.

In response, Russia attempted to use the existing media institutions in Azerbaijan and, in some cases, to create new media institutions to increase its impact on society. However, Russia was not successful in this. There was a very negative public perception of Russia and its role in the South Caucasus. Russian support for Armenia during its war with Azerbaijan, in addition to other factors, created an unfavourable environment for the Russian media influence.

A significant majority of the Azerbaijani public perceives Russia as an aggressor due to its activities in the region in the early 1990s. The public image of Russia deteriorated even further after its invasion of Georgia. According to a 2016 survey, only 16% of the population supported Azerbaijan’s integration into the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union, whereas the accession to NATO and the EU were supported by 72% of respondents. According to a 2017 nationwide survey, 32% and 51% of the Azerbaijan population respectively tend to trust NATO and the EU, while 26% favour the Eurasian Economic Union.

The statement made by Russian President Vladimir Putin, that Russia’s border does not end anywhere’, raised particular concerns in Azerbaijan, as Russian military activity in the Caucasus was on the rise. Azerbaijan sided with neither the EU nor NATO, but neither was it connected to any Russian-led organisations (the Eurasian Economic Union or the CSTO), leaving the country susceptible to Russian political and economic pressure, as it was experts interviewed at the time mentioned. So far, Azerbaijan has pursued a balanced policy, which has helped to establish friendly and effective relations with regional and international powers.

Azerbaijan also plays a significant role in the North–South transit corridor between Russia and Iran, as these three countries recently held a forum. There are some beliefs among Azerbaijan’s expert community that Russia wants to see Azerbaijan in the Eurasian Economic Union. The issue of the Azerbaijan’s membership of the Russian-led organisations was raised several times by Russian officials, including Sergey Lavrov, Minister of Foreign Affairs.

On the other hand, Russia is a vital economic partner for Azerbaijan. While oil and gas dominate Azerbaijan’s exports (around 90% of the total) and the main buyers of carbohydrates from Azerbaijan are Italy (the EU) and Israel, Russia is the major importer of the Azerbaijani non-oil products. According to the Centre for Economic Reforms and Communication and Committee of Customs, Russia was the main destination for Azerbaijan’s non-oil export in 2017 (553 million USD). The second country, Turkey, imported only 292 million USD worth.

To sum up, despite its negative image as Armenia’s strategic partner, Russia tries to maintain its influence in Azerbaijan, focusing specifically on several groups with which it may be able to hold sway.

Vulnerable groups

There are certain groups inside and outside Azerbaijan that are particularly vulnerable to the Russia’s state-run propaganda machine. Basically, these are the Russian community in Azerbaijan and the Azerbaijanis living and working in Russia. In addition, Russian is the second most spoken language in Azerbaijan, and although it does not have official status, it remains the lingua franca for several groups in Azerbaijani society, including members of the local political, economic, and cultural elite.

In the early 1990s, the Russian language lost its status as an official language in Azerbaijan. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the atrocities committed by the Red (Soviet) Army involving the death of the civilians, known as ‘Black January’ in Baku, and Russia’s position regarding the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in general, created a public outcry amongst the people. These events drastically diminished the prominent role of the Russian language in Azerbaijan, especially in urban areas. Due to a national awakening among Azerbaijanis and the mass emigration of ethnic Russians, the popularity of the Russian language deteriorated to a great extent and it lost its status as a language of communication in Baku.

However, Russian remains the most popular second language in Azerbaijan; 72% of the population speak at least basic Russian, while 7%, particularly concentrated in the urban areas, have advanced skills. The language is preserved and allowed to develop further due to the government’s current state policies, as it is widely taught in schools and at universities.

According to data published by the Ministry of Education of Azerbaijan, there are 15 Russian language secondary schools and 314 secondary schools that provide education both in Russian and Azerbaijani. Within the Azerbaijan independence period, not a single Russian language school was shut down; however, a decrease in the enrolment was observed. Overall, 82 535 pupils chose Russian as their language of instruction. Additionally, more than 450 000 pupils study Russian as a second language.

Due to its public image, Russia was unsuccessful in consolidating its influence among the larger social groups. Nevertheless, there are very specific groups that did fall under Russian influence.

There were 119 300 (1.35% of the total population) ethnic Russians living in Azerbaijan as of 2009, making them the third largest ethnic minority in the country. Experts interviewed for this research project believe that this group remains very susceptible to Russian propaganda, due to its continued use of the Russian language.

The latest official statistical figures put the number of Russians at 119 000, while the other major ethnic minorities, Lazgins and Talishes, comprise 112 000 people. Among ethnic-Russian Azerbaijanis, 98.9% consider Russian to be their mother tongue, and only 42.6% can speak Azerbaijani.

Several institutions reinforce the position of the Russian language in Azerbaijan. The Russian Orthodox Church is among those religious institutions which receive sympathy from the local authorities and the community at large. Russian speakers currently enjoy great availability of Russian-language literature and schools. Additionally, most universities in the country offer higher education programmes in Russian alongside Azerbaijani.

There are no special media tools or public influence mechanisms designed for Russian speakers living in Azerbaijan. Nevertheless, the role of this group in the formation of public opinion in the Azerbaijani and Russian media is obvious. In many cases, they try to display the reputation of Azerbaijan as a ‘country non-threatening to Russia’, and normalise relations between the two. According to interviews, many local media experts believe that, in many ways, Russia’s influence is very subtle and not openly traceable, as relies on diplomatic channels and other mechanisms to build contacts and deliver a message to the wider public through groups such as the ethnic-Russian minority in Azerbaijan.

The Azerbaijani government is somewhat concerned about pro-Russian sentiment among the Caucasian ethnic minorities. There are large numbers of Lazgi communities living in the regions straddling northern Azerbaijan and the Russian Caucasus. Russia was also relatively hospitable towards the nationalist members of the Talish communities. Many such nationalists reside in Moscow and other Russian cities. These two non-ethnic Russian groups are among the most vulnerable to Kremlin-led misinformation, influenced by Russia’s position.

Today, the Azerbaijani community residing in Russia consists of the ethnic Azerbaijani Russian citizens and the Azerbaijani economic migrants (long-term, short-term, and seasonal). According to the 2010 Russian Census, there are 603 070 Azerbaijanis residing in Russia, making it one of the top ten most numerous ethnic groups in the country. As pointed out by an expert consulted on the topic:

‘There are some social classes that are more vulnerable to Russian disinformation. Particularly, considering that some Azerbaijani citizens live in Russia, and Russia has a greater ability to influence them’.

The Azerbaijanis in Russia are well integrated in society and moderately active on the political scene; they have strong ties with the political establishment in Russia. The political discourse between Azerbaijan and Russia directly affected the lives of the Azerbaijanis living in Russia. From time to time, the group faced persecution from the Russian authorities, and there is evidence that the Azerbaijani community in Russia was used as a tool to influence decision-making in Azerbaijan.

The annulment of the registration of the All-Russian Azerbaijani Congress by the Russian Supreme Court caused a great concern for the Azerbaijani authorities. The organisation played a major role in strengthening socio-economic ties between the two nations, and its shutdown provoked several negative responses from the Azerbaijani government, which was known for its close association with the Congress.

The Azerbaijani community in Russia is heavily influenced by Kremlin-backed propaganda. As pointed out by an international relations expert:

‘The Azerbaijanis working in Russia are becoming the mediators of the disinformation exchange’.

The Azerbaijanis in Russia contribute quite a hefty sum to the economy of Azerbaijan. The ethnic Azerbaijanis in Russia are influential in building economic ties between the two countries. More than 80% of agricultural products originating in Azerbaijan are exported to Russia. The above-mentioned group established influential business contacts in Azerbaijan.

According to the World Bank, remittances to Azerbaijan are largely sent from Russia and total 2.2 billion USD. For the present, Russia hosts the largest workforce of Azerbaijani migrant labourers. Thus, the ethnic Azerbaijanis in Russia form a group which can have a significant impact on the domestic Azerbaijani situation.

Many Azerbaijani migrants working in Russia come from the country’s rural areas, and send their remittances to the rural areas of Azerbaijan, accounting for 1.8% of Azerbaijan’s GDP. Due to the petroleum price decrease, trade between those countries also shrank from $4 billion USD in 2014 to $2.8 billion USD in 2015.

Today, 600 Russian companies operate in Azerbaijan, 200 of them backed by 100% Russian investments. One of the interviewed economic experts mentioned this factor, pointing out the vulnerability of these social groups to Kremlin-led narratives and their subsequent prominent position from which they are able to influence Azerbaijan’s domestic developments.

There has been some increase in cooperation between Azerbaijan and Russia in education, characterised by intensive Russian courses financed by the Azerbaijani government and Moscow-funded educational and professional exchange programmes. The Azerbaijani students in Russia make up one of the largest foreign student groups in the country: while there are 72 000 foreign students in Russia, 20% of them, or roughly 14 000, are from Azerbaijan.

In many cases, the Azerbaijanis who got their education in Russia are members of the current cultural, economic and political elite in Azerbaijan. The Russian language actually became a cementing element for some of them. The new generation representatives who join the Russian-language schools or other educational programmes are mainly influenced to do so by this community. Hence, despite having no ethnic or other ties to Russia, the use of Russian as a language of the Azerbaijani elite makes those who pursue such a path vulnerable to Russian cultural and even political influence, through the media content to which they are exposed.

Media landscape

In the second half of the 1990s, due to the Azerbaijan’s pro-Western stance, a decrease in the number of students using Russian, the emigration of ethnic Russians and strict media control, Russia was able to exert some limited influence on the Azerbaijani media.

In the early 2000s, with the increasing popularity of news portals on the Internet, the local government started sponsoring several Russian-language websites. Their main aim was to disseminate pro-Azerbaijani narratives in the post-Soviet countries where the Russian language still held prominence. Nevertheless, this development led to intensified contacts with Russian media outlets, and allowed Russian disinformation to spread in the Azerbaijani media.

After 2012, Russia changed its strategy towards Azerbaijan, supporting several media outlets operating in Azerbaijan. For example, in 2015, the Russian-sponsored media channel Sputnik Azerbaijan started to operate in both Azerbaijani and Russian. Overall, the main goal of the Russian media outlets in Azerbaijan is to create a positive image of Russia among the public.

According to Alexa.com, Sputnik.az does not rank among the Top 50 websites in Azerbaijan. Only the following Russian-language news sites are in that listing:

- Oxu.az

- Milli.az

- Big.az

- Musavat.com (opposition party newspaper website)

- Haqqin.az (in Russian, pro-governmental)

- Yenicag.az

- Qafqazinfo.az

- Day.az (in mixed languages, but mainly Russian, independent)

- Axar.az

- Lent.az

- Sonxeber.az

Sputnik.az is ranked as 94th in Azerbaijan. The Russian ‘Sputnik’ news agency is gaining momentum, but not yet among the most influential sources.

The country enjoys free access to the social networks. However, some members of parliament have recently called for limits on access to social media platforms to avoid a ‘foreign-sponsored uprising of a kind similar to the Arab Spring’. Nevertheless, in May, 2017, the authorities limited access to websites such as RFRL, Meydan TV, and other online TV channels. In 2017, the Reporters without Borders Press Freedom Index placed Azerbaijan 162th out of 180 in its ranking. In 2017, Freedom House ranked Azerbaijan as ‘partly free’, granting it an overall Internet freedom score of 58 out of 100.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, 10 reporters are currently imprisoned in Azerbaijan. In previous years, there were several high ranking cases involving journalists being arrested, namely connected to Eynulla Fatullayev, Avaz Zeynalov, and Mehman Aliyev. All were later freed. According to government officials, the reasons for these journalists arrests were not related to their media activity. Officially, they were charged under articles of the Criminal Code, including in relation to tax evasion.

The majority of the news agencies and online sites also publish information in Russian (and English).

Alongside the state-owned broadcasting company AzTV and public broadcasting company Ictimai TV, several other TV broadcasting companies exist:

- 14 district TV broadcasting companies

- Five national non-state TV broadcasting companies

In addition, ATV International is a private satellite broadcasting company, while Idman-Azerbaijan and Medeniyyet-Azerbaijan are TV channels specialising in sport and culture, respectively. There are also about 30 Internet TV channels in Azerbaijan.

The prominent print media outlets are the following:

- Ekho (in Russian)

- Azerbaycan (a government newspaper)

- Yeni Azerbaycan (the ruling party’s newspaper)

- Azadliq (grouped around opposition parties)

- Yeni Musavat (grouped around opposition parties)

Basically, all major Azerbaijani information agencies have a page for publications in Russian:

- Azertac (official state news agency)

- APA

- Turan

- Trend

- APA

Additionally, all major Russian TV channels are available through cable TV in Azerbaijan.

The main problem for the pro-Russian media outlets is the generally negative image of Russia. Even a cursory review of the daily media reveals that the Azerbaijani media openly view Russia as the main international force to help Armenia to gain control over Nagorno-Karabakh. Hence, there is little public favour towards Russia, and Russia cannot be influential in the Azerbaijani media simply by spreading pro-Russian news.

There are several factors which may work in favour of Russia to get Kremlin-backed messages to the public more successfully. One important point in this regard is that the living standards of journalists and media workers in Azerbaijan is low. According to some NGO and trade union reports, a print media journalist earns about 400 AZN per month (450 EUR before devaluation, and 350 EUR currently). The average salary for a broadcast media journalist is around 600 AZN (840 EUR before devaluation, 520 EUR currently). Given the high cost of living in Azerbaijan, these salaries place reporters in the lower middle class.

The underlying reason for such low salaries is that media management advertising practices are not yet fully mature. This makes media companies financially weak, with rather low salaries for their employees. As a result, the majority of media outlets employ semi-professionals, and thus investigative journalism is weak and fact-checking desks are largely absent.

Due to the lack of the social security programmes (except the government-funded housing projects for a limited number of media professionals) targeting journalists and improving their living standards, journalists tend to seek external financial sources. This creates an opportunity for them to be recruited by external interest groups, including Russian ones.

The media trade union in Azerbaijan is also relatively weak. The legacy of the Soviet-era trade unions still persists, even though current understandings of their purpose and functions are not the same. Thus, journalists lack the skills to obtain fair job contracts that could ameliorate their work and living conditions. This is why the quality of journalism in Azerbaijan is poor.

Even though media in Azerbaijan is quite diverse, it is in fact highly politicised. The media bodies grouped around the government and opposition parties set the media agenda in the country. As a result, editors-in-chief completely dominate the tone and content of the print media entities, and lack any interest in actual news reporting, while the political process results in media being highly biased and strongly focused on special interests.

Legal regulation

In 1998, the official media censorship left over from the Soviet era was revoked by presidential decree. This became a turning point for the independent media in Azerbaijan. From then on, media content was mainly in the hands of the media outlets’ editorial offices. In most cases, the legal media owner in Azerbaijan is also its editor-in-chief. In other words, this person is both a news reporter and an entrepreneur. The Azerbaijani ownership model does not follow the standards of European countries, in which ownership/business matters should be separated from editorial policies.

Currently, independent media bodies (see Institutional Setup) consist of professional journalists and managers regulating media.

The main legal regulatory documents for the media are the following:

For the broadcasting media:

- Law on Radio and TV Broadcasting (N 345-IIQ), adopted in 2002

- Law on Public TV and Radio Broadcasting (N 767-IIQ), adopted in 2004

For the print and online media:

- Law on Mass Media (N-231), adopted in 1992

One of the legal problems regarding media in Azerbaijan is the lack of media ownership transparency. According to the law on the state registration of legal entities, ownership information can only be disclosed with the owner’s approval. This makes it extremely difficult to publish a list of owners of media entities. Hence, it is not clear if there are any media organisations in Azerbaijan owned by foreign groups.

In spite of that, the country tries to protect its media sphere from foreign influence and, especially, from foreign funding. In 2014, the Azerbaijani parliament passed a law restricting the financing of non-governmental and civil society organisations and, subsequently, largely limiting their influence on individuals and the public. The incentives targeting foreign influence (including Russian) in the country came directly from the government. Russian influence in the media of Azerbaijan is limited mainly due to the high level of state control.

Nevertheless, despite the state control of media, some experts believe that there is much more to deal with:

‘There is a need for a national strategy. I do not think we have any effective counter-influencing measures. There is a need for programmes to improve the professionalism of journalists, and the first initiative should come from the government. There is also a need to identify the short-term targets. Some counter-influencing measures should be implemented as well’.

Another expert mentions the late response of the government institutions to the information challenge:

‘The operative response of state agencies is a problem. When the event occurs, the social media is very quick to react. During that time, after half an hour, one day, half a day, while public authorities do not provide any information on the issue, people start to panic’.

The Law on Information Security was adopted in 1998 (N-432-IQ), and is generally considered to be inadequate. Expert opinions differ in some cases, and rather than seeing the overall legislative base as being inadequate, they criticise its implementation and the technology behind it:

‘According to the mass media law, the establishment and dissemination of information through investments from abroad is prohibited. The media budget cannot have more than 30% of funds from abroad… the attacks cannot be technologically avoided. From a technological point of view, the safety of our information space has never been provided for’.

In 2017, following parliamentary amendments to the law, the online media were considered equal to the print media, with the same regulation for content.

Institutional setup

Since Soviet censorship was abolished, two self-regulatory bodies have been established:

- the Press Council for the print media

- the National Broadcasting Council for broadcasting companies

The main objective of the Press Council is to execute the ‘Ethical Code of Azerbaijani Journalists’, adopted by the First Congress of Azerbaijani journalists in 2003. At a later stage, a joint working group was established by the OSCE Baku Office and the Press Council, where the latter’s role was to promote and enforce the Code. The chair of the Press Council of Azerbaijan has since 2015 been a member of parliament.

The National Television and Radio Council was established in 2002 ‘to provide the implementation of state policy in the field of television and radio broadcasting, and to regulate this activity’. Its board members are appointed by presidential decree, but the president cannot dismiss them. The Council is fully funded by the state budget, but declares itself independent in its activity. The Council is responsible for providing broadcasting licences. Hence, this limits the options for foreign-funded broadcasting companies, including those from Russia, to operate in Azerbaijan. However, it is also worth mentioning that the major Russian TV programmes are available via several cable television companies in Azerbaijan.

There is also the State Fund for Support of Mass Media Development under the Azerbaijani President (KIVDF). This is designed to improve the financial stability of media entities in Azerbaijan. One of the main aims of the Fund is to limit the activity of foreign influence groups in the media sector by providing some alternative funding options.

Media literacy projects and digital debunking teams

The overall civil society environment in Azerbaijan severely restricts the capability of local NGOs to function and implement various projects, including media literacy projects. Since there are very limited options (mainly for non-political issues) for foreign funding, the media NGOs are not capable of carrying out full-scale media literacy projects.

Due to the limitations imposed on civil society institutions, there is barely any source of information on non-governmental organisations, research institutions or digital debunking teams that openly counter Kremlin-backed propaganda in the country. Some experts interviewed for this research pointed out the importance of striking a balance between media freedom and the information security.

Previously, several projects implemented within the framework of the UN and the Council of Europe, and addressed the need to increase media literacy among the general population. Nowadays, such programmes are harder to come by. In previous years, some organisations (including the Journalists’ Trade Union and Press Council) also implemented projects on ethical journalism standards and an ethical code for the journalists, increasing the professionalism of journalism and the capacity to withstand the foreign propaganda pressure.

In terms of digital debunking, a 2016 event hosted in Tbilisi (involving some young politicians from Azerbaijan) included two-day training provided by StopFake project members, on the detection and confrontation of foreign propaganda and the political fact-checking. The StopFake project periodically includes information relevant to Azerbaijan on its website. Another initiative from 2017 came on the part of the U.S. Embassy, providing scholarships allowing Azerbaijani journalists to take an e-course to help them improve their skills in recognising fake news and exposing inaccuracies, and to study best practices in debunking and communicating the truth around the misinformation.

Despite the aforementioned sporadic initiatives, organised efforts and systematic debunking are hard to implement. There are several news sites and forums which report the wrong statistics, such as the Azerbaijani Language Forum on disput.az, where there are examples of users presenting dubious information and debating its veracity.

Conclusions

While Azerbaijan did not align itself with either the EU or NATO, neither did it join any Russian led-projects. Without protection from NATO yet cooperating with the EU, particularly on the energy market, Azerbaijan has become a hot spot for Russian interests.

Up until now, Azerbaijan’s balanced politics have helped it to build neutral and friendly relations with all regional and global powers. Azerbaijan did not choose sides, and continues to be a part of strategic energy projects, providing alternative gas routes to the global market, and irritating Moscow.

In Azerbaijan, Russia is largely considered to be a power that meddles in regional conflicts, and its role in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is not viewed as neutral. Hence, there is relatively low public support for the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union, and Russia’s image in Azerbaijan is rather negative in general.

Civil society has taken a strong hit in Azerbaijan in recent years. The role of NGOs and the influence of think-tanks in the society has been seriously degraded. Hence, the majority of incentives for limiting the Russian influence in Azerbaijan come from the government, and not from civil society members.

Tight state control over broadcasters and limited foreign funding have helped the government to balance out Russia’s direct influence in Azerbaijan.

There is no legal document imposing censorship on the mass media in Azerbaijan, and, as it is declared, it is regulated by the reportedly independent bodies:

- National Television and Radio Broadcasting Council (for the broadcasting companies)

- Press Council (for the print and online media)

The State Support Fund for the Mass Media Development (KIVDF) also plays an important role in regulating media in Azerbaijan.

The media is diverse, but camped around the political parties and highly marginalised. Since there is no political force openly supporting Russian politics, the media outlets dependant on these political parties do not express any sympathy toward Kremlin.

The use of the Russian language (alongside other foreign languages, including Turkish and Persian) is prohibited on nationwide and regional television and radio channels. The Azerbaijani language predominates in the mass media. Many newspapers are published in Russian, and in many cases, they are on the top of the rating lists, shadowing the Russian sponsored agencies such as ‘Sputnik’.

Recommendations

- To increase the effectiveness of the state agencies and their work with the media and public agents.

In many cases, the operative responses of the media outlets addressing some social and political issues are provided very late, creating room for speculation. Such speculation is shared and discussed by the ‘yellow pages’ and social network users. This gives some opportunities for foreign influence groups to take over the information sphere in Azerbaijan and feed it with the fake news, to effectively advertise their own values.

- To develop journalists’ professionalism.

Journalists’ professionalism and adherence to ethical rules of remain low. Many reporters are inadequately trained and lack professional experience. Unprofessionalism damages public confidence in local media bodies, as pointed out by interviewees taking part in this study. This also increases the opportunities for foreign players to spread ‘catchy’ but fake news.

- To strengthen the social security of media workers.

According to reports of the journalists’ trade union organisations, media workers’ salaries remain rather low. Due to social security issues and low living standards, media workers tend to fall under the influence of foreign groups.