Introduction

After the collapse of the Soviet Union and the proclamation of independence by Georgia, the Kremlin continued to actively meddle with the domestic politics of the country. Russia supported separatist forces in the regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. In 2008, Russia undertook military intervention on the territory of Georgia, followed by war with Georgia. The Kremlin recognised the self-proclaimed sovereignty of the regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia; concluded agreements with the de facto governments, by which it strengthened its military, political, and economic positions in the occupied territories.

The occupied territories give Russia major political leverage over Georgia. Russian bases in the regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia pose serious problem in terms of security of the population. One base is just 20 km away from Tbilisi, in the Akhalgori region. The military units from this base provide major support to the illegal separatist authorities in the regions. Provocations continue periodically, such as the so-called ‘borderisation’, abductions of local people by the Russian troops, etc.

Following the 2012 parliamentary elections, a new political force came to power that actually started ‘to reset’ relations between the Kremlin and Tbilisi. This brought a partial restoration of economic relations, as well as trade between the two countries. According to data from 2017, Russia is Georgia’s largest export destination, with 14.1% (274 million USD) of Georgian products exported to the country, compared to 2016, when Russia came in third (132 million USD) after Turkey and China. Despite an increase in export to Russia, the largest share (24%) of Georgian export goes to EU countries. Russia comes second as the largest importer of Georgian goods, following Turkey (532 million USD). Most imports come from the EU (28%).

According to data published in 2012, there are up to 800 000 Georgians living in the Russian Federation. Whereas, in the same period, Georgia’s population was 4.498 million. Seasonal migration is also regular among ethnic minorities.

‘Every year, once they finish cultivation of their land, men leave for Russia to work and return to harvest the crops. It is significant income for their families’.

The number of emigrants is reflected by money transfers: according to NBG data from 2017, the largest number of transfers to Georgia were made from Russia; we get the same picture based on statistics for the last 10 years, e.g., in May 2017, 115.4 million USD were transferred to Georgia, of which 37.8 million USD came from Russia (33.4%), 12.1 million USD came from the US (11.6%) and 11.7 million USD from Greece (10.6%).

Similar to Russia, the majority of Georgia’s population practices Russian Orthodoxy. In 1917, the Georgian Church regained its independence, which was originally taken from it by the Russian Empire back in 1881. Considering the common religious beliefs, the Georgian population is supportive of nations practising the same religion, including Russians.

The Russian language factor should also be taken into account. In most cases, Russian is the main foreign language for the elderly population in Georgia. Overall, 72% of citizens report their knowledge of Russian language as high. Although the number of those who can speak English is steadily rising (2008, 12%; 2017, 20%), especially among the youth, the difference between Russian- and English-speaking skills is still quite visible in the society. Proficiency in Russian increases the dependence on Russian media and contributes to the threat of disinformation from Russian-language media.

Vulnerable Groups

The population of age 50 and older has spent a significant part of their life in the Soviet era. They speak Russian, have people-to-people contacts within society in Russia and many feel nostalgic about the Soviet past. In addition, the mentality they built in the Cold War period offers good grounds to cultivate anti-Western feelings and to strengthen loyal attitudes towards Russia as the legal successor of the USSR and an opponent of the West. The majority of the experts interviewed believe that one of the main goals of the Kremlin’s disinformation policy in Georgia is to instigate a sense of nihilism about European integration.

Another vulnerable group to pro-Kremlin propaganda in Georgia is ethnic minorities (Armenians, 4.5%; Azerbaijanis, 6.3%). A lack of knowledge of the Georgian language among the Armenian and Azerbaijani populations, living in the southern and south-eastern parts of the country, is a serious barrier to their integration into Georgian society. As a result, it is difficult to keep this population informed through Georgian sources and leaves space for foreign, including Kremlin-governed disinformation to fill the void. As one of the interviewed state officials put it,

‘for years, the state did not pay enough attention to these people, which distanced them from the process taking place in Georgia. Now we are trying to fill this gap with state programmes. The language barrier is another obstacle and we are working on this too’.

For these reasons, ethnic minorities as well as the Russian, Armenian, Azerbaijani, and Turkish populations prefer watching programmes where the language is familiar and the content more interesting, this works against Georgia’s efforts to counter disinformation.

Economic factors make other groups vulnerable to pro-Kremlin disinformation policy. Of the Georgian workforce, 52% is employed in the agriculture sector, of which 98% are self-employed. The Russian market, with its size and lower quality standards, plays an important role when it comes to selling products from this sector. As the openness of the Russian market to foreign goods is determined mainly by the Kremlin’s political agenda, Georgian entrepreneurs who are dependent on the Russian market have become extremely vulnerable to the pro-Kremlin propaganda.

The large Georgian diaspora and their economic and other links with their families in Georgia provide the Kremlin with favourable means of provocations in terms of disinformation and exerting other kinds of influence.

We may also consider the conservative portion of active believers belonging to the Georgian Orthodox Church as vulnerable to Kremlin disinformation. The anti-western context is topical for them and a pro-Kremlin narrative is often heard as the alternative. This narrative is often revealed in the preaching of particular clerics. But as Metropolitan Andria notes, the Patriarchate of Georgia supports the choice of the Georgian people about the integration into the European and Euro-Atlantic space. One of the frequent myths concerns the concept of Moscow as a Third Rome, which gives Russia special religious importance in the Orthodox world.

Although the majority of Georgia’s population supports the integration of the country into Western geopolitical structures (according to 2017 data, 80% and 68% of the Georgian population is supportive of integration with the EU and NATO membership, respectively), and that the relevant foreign policy obligation has been encoded in the country’s constitution, yet a part of the society does not agree with it. Individuals who represent mainly the radical part of the nationalist community are major targets of pro-Kremlin propaganda. This group is divided into two sub-groups. There are political and social forces, who overtly conduct pro-Kremlin policy.

‘He put Russia on its feet, … to tell you the truth, I would wish the same president for my country as Vladimir Putin’,

Nino Burjanadze, former Speaker of parliament and the leader of the Democratic Movement – United Georgia told Deutsche Welle.

The other part of the radical nationalists stays aloof from clear pro-Russia policy, although they cultivate Euroscepticism and anti-Western feelings. They regard themselves as pro-Georgia forces.

‘These radical right-wing forces are anti-globalists and against Georgia’s European and Euro-Atlantic integration. Their aspirations coincide inadvertently in some issues with the goals of the pro-Kremlin propaganda’,

Malkhaz Gagua, editor of the newspaper Rezonansi said. Given this factor, these groups are the most susceptible to pro-Kremlin narratives.

Media Landscape

Georgia has a broad and diversified media landscape and the most liberal media laws in the entire Southern Caucasus region. There is virtually no direct state censorship, although in some cases, private media reflect the political orientation of media company owners, on whom they depend both financially and politically.

Georgia’s media landscape continues to face major challenges that have only grown since the country signed the EU Association Agreement in June 2014. In that agreement, the Georgian government committed to maintaining European standards of media freedom as well as media law, but neither journalists nor legal experts yet have the ability and experience to ensure that the necessary changes laid out in the agreement have been implemented.

Media ownership in Georgia is transparent. None of the major media outlets are directly owned by any political force. Several cable and internet broadcasters are owned by anti-Western organisations. Their declared income is quite small, so it is unclear what kind of resources these channels have for broadcasting.

Regarding online media, the transparency requirements of ownership do not apply, therefore citizens do not have information about the majority of websites. Interviews carried out by Transparency International Georgia and systematic observations on information websites have shown that during the last few years, there have appeared media outlets online that are based on political preferences. These groups intensively use social networks to disseminate information. Given their existence, providing audiences with fact-checked and high-quality journalistic information is becoming more difficult.

Over the past few years, some news websites have been actively involved in anti-Western propaganda and their rhetoric is often expressed in a xenophobic and homophobic context.

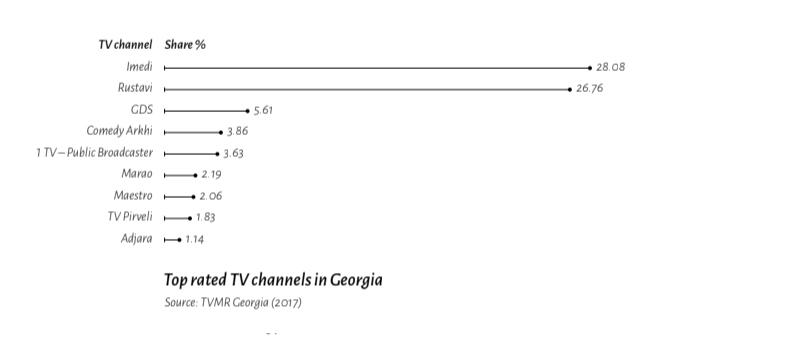

Chart 1 shows the top-rated TV channels in Georgia according to data from in 2017 compiled by the television Audience Measurement official licensee company TVMR Georgia. These channels are less likely to be influenced by Kremlin disinformation. Most of the respondents note that Kremlin propaganda does not spread on the popular TV channels. However, they mention media outlets that often spread Kremlin propaganda. The TV station Obiektivi is one of the most frequently mentioned television broadcasters carrying out a pro-Kremlin, Turkophobic, xenophobic, and homophobic editorial policy. According to the mentioned data (TVMR GE), Obiektivi is not among the country’s popular channels.

Anti-liberal, ethno-nationalistic, and pro-Kremlin propaganda is also spread by print and online media. In this regard, it is important to note the newspapers Asaval-Dasavali, Alia-Holding and online editions Georgia and the World and Saqinform. According to the Media Development Fund’s (MDF) Media Monitoring Report 2016, anti-Western messages are spread by the following media outlets: 1) Georgia and the World; 2) Asaval-Dasavali; 3) Saqinform; 4) Obiektivi; 5) Alia-Holding. They publish concepts such as Georgian society, in cooperation with Orthodox Russia, is the guarantee for a better future for Georgia; that by entering NATO, Georgia will be reluctant to live under Turkish dictate; that the US is completely powerless against Russia’s military actions; and so on.

Since 2012, Georgian media has experienced significant changes to become much more pluralistic, as confirmed by respective international rankings. In the summer of 2015, Georgia fully switched to digital broadcasting, which should definitely be regarded as a positive development for the Georgian media environment. Furthermore, several new TV stations were launched and some old ones resumed broadcasting. The new TV Pirveli emerged in the Georgian television space, while the TV company Iberia resumed broadcasting.

There are non-profit organisations in Georgia that fight disinformation, propaganda, and the dissemination of myths through media monitoring. One of the organisations that conducts ongoing media monitoring is the Georgian Charter of Journalist Ethics (GCJE), established on December 4, 2009. GCJE’s mission is to increase media social responsibility by observing professional and ethical standards and creating self-regulating mechanisms. Representatives of media organisations from the regions and the capital signed on to 11 principles within the scope of the GCJE.

The GCJE allows citizens to appeal cases of journalists’ ethical violations. In addition, GCJE conducts surveys in the media space, as well as monitors the usage of hate speech, disinformation, and propaganda. Because of this activity, it became a member of the Consultation Committee established to fight propaganda. The Committee is composed of representatives of the self-regulation councils of the following countries: Georgia, Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Russia. The committee was set up to fight propaganda.

The GCJE reviews reported cases of a violation of professional standards on request, although it does not impose any sanctions on the offender. Since 2010, the GCJE has reviewed 163 cases by different media outlets.

Since 2008, surveys on local media have been carried out by MDF, which, among other issues, supports freedom of expression, ethical journalism, accountability, media knowledge, and diversity. Its ‘Myths Detector’ format, which the MDF created in the framework of the EWMI project, works on identifying myths disseminated in the media and verifying fake information.

The legal, political, and economic environment in the country has a key impact on media. In a democracy with an orderly legislative base, free from state interference in the economy, and with freedom of expression actually practiced, media enjoy true independence. Freedom House is an international organisation that studies these factors and publishes annual reports on the level of freedom of media in many countries.

According to the 2017 media freedom report by Freedom House, Georgia received 50 points and is among the countries where media is partly free, whereas in terms of legislation, Georgia received 13 points out of 30, in the political environment, 21 points out of 40, and in the economic environment, 16 points out of 30. Georgia has been placed among the partly free countries in terms of media freedom for several years now, with the following press freedom indexes: 47 in 2014, 48 in 2015, 49 in 2016, and then 50 in 2017. Considering the results of the Freedom House survey of 2017, Georgia has the best indicators of the freedom of press in the post-Soviet space.

Freedom House publishes annual reports on freedom of the internet as well. According to the results for 2017, Georgia received 24 points out of 100 and was assessed as free. In access to the internet, the results have improved compared to 2016. According to the report, 50% of the population in Georgia has access to the internet. This may be the result of constitutional amendments adopted by parliament on September 26, 2017, which incorporate access to the internet as a basic human right.

The main source of information on political processes and of the current news in Georgia comes from television and the internet. According to the NDI survey, the percentage of information received from traditional media is significantly high compared to the amount of information obtained from internet sources. Nevertheless, according to data from 2017, the share of information obtained from the internet has increased, maybe at the expense of television. While, according to data from 2016, 77% of the population regarded television as the primary source of information, in 2017 this indicator decreased to 72%, and usage of the internet increased from 14% to 21%.

Georgian law on broadcasting obliges the public broadcaster, a state-funded television station, to promote the main foreign policy goals of the country, including its European and Euro-Atlantic integration. However, it should be noted that the public broadcaster has not done enough to meet this obligation. This is proved by the decision of the public broadcaster’s management to close its bureau in Europe, blamed on a lack of financial resources. The bureau was covering important visits in the countries of Europe, broadcasting live from different hot spots, and prepared feature stories on the EU and NATO. This proves that the national media operates in its financial interest.

Natia Kuprashvili, head of the Journalism Resource Centre, believes it is vitally important for the Georgian audience to have access to European media products and that covering issues related to European integration and European values in the Georgian media space is of primary importance for the country.

The public broadcaster is also obliged to broadcast programmes in minority languages and about minorities, as well as programmes prepared by minorities in respective proportions. Apart from this, the Georgian government has adopted the ‘State Strategy of Civic Equality and Integration’, which among other goals highlights the importance of increasing access to media and information as a step towards promoting full and equal engagement of ethnic minorities in the civic and political life of the country. The strategy states that ‘media plays a special role in successful progress of the integration process both through its coverage of topics related to ethnic minorities and their involvement’. The strategy also envisages improving ethnic minorities’ access to information in their native ethnic languages and their inclusion in the common information space as a part of the integration process. The strategy places the leading role on the public broadcaster in this process. Despite all this, there is no clear-cut state policy at this point that would prompt ethnic minorities’ interest in the foreign language-based content. The results of the NDI public survey depicts the popularity of non-Georgian TV channels among the ethnic minority populated regions at 52%, mostly Russian news programmes. Satellite dishes are used to get information in these regions. However, these regions are gradually switching to digital broadcasting.

It should be noted that after the 2008 war, Georgian cable TV companies stopped transmitting Russian channels upon a verbal directive from the government. All Russian channels were also removed from cable TV packages. However, after the change of government in 2012, broadcasting of Russian channels resumed. For example, nowadays, more than 50 Russian-language channels are available in the 119-channel package offered by the digital TV company Global TV. Also, about 90 Russian-language channels are included in the 222-channel package offered by operator Silknet.

Legal Regulation

The democratic form of government implies that the population makes the decision independently, which is impossible without an accurate, fact-based, balanced, ethical, and responsible media environment. There is no significant problem in Georgia in this regard at the legislative level, as the ‘Law on Broadcasting’ in force since 2004 is liberal. The law provided for the creation of a public broadcaster independent from state interference and builds on the freedom of expression and thought. This makes it difficult to fight disinformation and propaganda in the country using legal leverage.

Broadcasting activities are regulated by the National Regulatory Commission, which is independent from any state agency. The legal status of the commission is determined by the law of Georgia on electronic communications, adopted in 2005.

Pursuant to the broadcasting law, the Georgian National Communications Commission (GNCC) adopted a ‘Code of Conduct for Broadcasters’, which aims to ensure that all broadcasters have an equal responsibility to observe professional ethical norms and accountability to society. The code helps journalists, publishers, and broadcasters resolve issues related to ethics and also obliges them to provide reliable, accurate, and fact-based information to their audiences. Based on Article 7 of the code, broadcasters are instructed to establish an effective self-regulation mechanism: ‘Broadcasters have the right to choose an effective self-regulation mechanism, in accordance with this Code, which meets high professional standards and provides for transparent and effective complaints handling procedure and ensures timely and substantiated response to them’.

The interviewed experts and civil servants unanimously agree that establishing stricter rules in this field will be counterproductive. However, Sulkhan Saladze, GYLA Chairman, notes general shortcomings in the constitutional legislative base:

‘in terms of the security of information, the legislative base needs substantial improvement. A holistic government vision and the taking into account public opinion are the most important for such improvements’.

The Personal Data Protection Inspector of Georgia believes that analysis of the law on ‘Security of Information’, identification of shortcomings and assessment of its implementation is possible. She believes it is important to increase the introduction of standards of security of information and to increase the financing of the relevant agencies to this end.

According to media representatives, the media regulations in Georgia are liberal, which promotes media pluralism. They regard the implementation part as the most problematic.

‘I do not see the necessity to change the law, but I think that the state through the regulation commission should monitor those media means, which contribute to hate speech and controversy’,

Khatia Jinjikhadze, the deputy executive director of the Open Society Georgia Foundation (OSGF) said.

In Focus

Photos used when disseminating propaganda often do not relate to the article in question but are often misrepresented, either by being used out of context or by being doctored, e.g., in 2017 www.digest.pia.ge and Georgia and the World published a statement by Jondi Baghaturia, the leader of Kartuli Dasi, which spoke about raids against Orthodox Christian churches and cathedrals in Ukraine, as well as about physical violence against clergy and congregation. Together with the statement, Jondi Baghaturia had uploaded a photo on social networks, which the news agencies used. The Myths Detector revealed that the photo was not related to the raid on the Orthodox church, but an explosion in a church in the town of Zaporizhia, which resulted in the arrest of three criminals. Apart from this type of debunking, the Myths Detector works to reveal how Kremlin forces try to spread Turkophobic attitudes in Georgia.

Another example of photo manipulation is from May 29, 2017, when the publication Asaval-Dasavali spread information that NATO had received a new uniform for transgender military service personnel. This information included photos the newspaper claimed were of transgender service personnel from NATO. However, the people in the photo were actually representatives of the American Civil Liberties Union, and not NATO troops.

Mediachecker.ge published an article titled ‘Trade in Organs and pro-Kremlin Propaganda’ which reported on an article by Sakinform on September 12, titled ‘Lonely persons are abducted in Kyiv, ripped into pieces and buried secretly—the underground hiding place of Mikheil Saakashvili’s wife was found!’ The news agency asserts that lonely people were being abducted in Kyiv, ripped apart and then buried secretly, and a well full of human bodies was found near Kyiv. But, this information was not confirmed and similar articles relating to the same story can only be found in Kremlin propagandistic publications—rusgambit.ru, Pravda.ru, news.sputnik.ru, etc.

On January 27, 2018, the TV Obiektivi broadcasted a news report prepared by Channel 1 of the Russian State television service. According to the programme’s host, Valeri Kvaratskhelia, the coverage depicts the downing of an American ‘invisible’ aircraft by Soviet weapons, to emphasize US military weakness. Although the Myths Detector found out that the video material provided by TV Obiektivi was not related to the case at all, rather it depicted an air show event in the US state of Maryland in 1997. In fact, the reason for the downing of the so-called ‘invisible’ American aircraft—presumably an F-117 stealth fighter that crashed in the former Yugoslavia—is still unknown.

Institutional Setup

A large percentage (45%) of the experts surveyed within this research project believe that the level of institutional development in the field of information security is low.There is a law in Georgia protecting the security of information, which establishes rights and obligations, as well as state border-control mechanisms in this area.

Regarding government bodies, there is the ‘Communications Strategy of the Government of Georgia on EU and NATO Membership 2017-2020’, in which the Kremlin’s information war is considered a significant threat to Georgia. According to the government’s 2014-2017 strategy, different structural units were established in various departments with the goal to coordinate EU and NATO integration processes.

There is the National Security Council of Georgia, whose obligation is to deepen cooperation in different areas. However, according to amendments to the constitution, in 2018, following the presidential elections, the National Security Council will be abolished. During peacetime, the functions of the Security Council will be distributed to the executive branch of government, led by the prime minister, and during war-time, responsibility will pass to the Defence Council, which will be subordinated to the president. According to the Secretary of the National Security Council, Davit Rakviashvili,

‘the abolition of the Security Council is a big mistake because there will be no institution where the president, the prime minister, and the speaker of parliament will meet each other to discuss security issues’.

There is a Cyber Security Bureau in the Ministry of Defence of Georgia. Under the umbrella of interagency cooperation, the Cyber Security Bureau cooperates with the Data Exchange Agency, Cybercrime Division of the Central Police Department, State Security Service, State Security, and Crises Management Council, etc. In 2015-2016, within the framework of interagency cooperation, the cyber-exercise Cyber Exe was held at the national level with the involvement of IT specialists from the state and private sector.

Concerning the development of strategic communications, in 2018, the US embassy in Tbilisi began financing the Strategic Communication Programme in Georgia, which is an important mechanism for strengthening cooperation between the US and Georgia.

As the conversation with the interviewed civil servants revealed, the state bodies try to counter challenges related to the security of information on their own, without the assistance of other state agencies.

‘There is no permanent interagency cooperation set up in this field, (and) cooperation may take place only on a specific issue’,

Tengiz Pkhaladze, an adviser to the president of Georgia, said.

David Usupashvili, the former Speaker of the Parliament, sees another barrier to the lack of cooperation in the decision to dissolve the Security Council:

‘to counter a major challenge such as the security of information, we need to permanently update methods and develop a common state policy. The Security Council could play an important role, including in terms of cooperation’.

Cooperation between governmental and non-governmental organisations is more intense in the area of information security. Joint campaigns have been implemented mainly on issues related to European and Euro-Atlantic integration to provide accurate information to the public. According to Tamar Kintsurashvili,

‘we cooperate with the information centres of NATO and the EU and we share the results of our daily monitoring’.

There is a different picture when it comes to cooperation within the non-governmental sector. Almost all the interviewed representatives of NGOs confirm they cooperate with other civil-society organisations within various non-governmental alliances and campaigns. Such formats include the Eastern Partnership platform, Alliance of Regional Broadcasters, and the Coalition for Euro-Atlantic Georgia. There are also small-scale partnerships between two or three organisations aimed at identifying disinformation, strengthening regional media, and implementing objective information campaigns to counter the propaganda activities.

Digital-Debunking Teams

Despite active cooperation among civil-society organisations and legal regulations being in place, fake and inaccurate information is still disseminated in the Georgian media space. Chapter 3 of the ‘Code of Conduct for Broadcasters’ refers to the protection of due accuracy—the broadcaster is obliged to take all reasonable measures to ensure that facts are accurate and sources of information are reliable, while Article 5 stipulates that broadcasters should refrain from staging and restaging events in news and programmes in order not to mislead the audience.Kremlin disinformation and myths are spread in Georgia in different ways—some of the myths help to disseminate the Kremlin narrative and to cultivate an understanding among society that Russia is the only solution for Georgians; another part attempts to change public opinion and to increase support for the pro-Kremlin narrative by disseminating anti-Western messages. Also, Russian myths often relate to the sense of national identity.

‘Pro-Kremlin propaganda is spreading in Georgia under the guise of anti-Western propaganda. No one has yet measured the effect of such propaganda, but it is a fact that some part of the population shares such propaganda. We find in certain media anti-Western narratives”,

Jinjikhadze, OSGF’s deputy executive director noted. For instance, on December 27, 2017, the online edition of Georgia and the World published an interview with a cleric in which the journalist says that incest is recognised as a norm in Europe.

Another myth, which the Kremlin supports as its main focus of propaganda, is the idea of a neutral Georgia, viewing as a risk its joining NATO. Pro-Kremlin forces actively try to generate scepticism in Georgian society and destroy all expectations related to the country’s integration into NATO.

Apart from legislative regulation, monitoring and analysis of journalistic products in Georgian TV stations, online, and print media is done by other means as well. Representatives of media organisations undertake daily analysis of broadcasters, online media (social networks), and print media. OSGF is actively involved in this process. One of the priority areas of the foundation’s activity is strengthening and supporting media organisations that operate with accuracy, objectivity, and good quality information.

‘We are not building a counter narrative; we are constructing a correct narrative and helping local media cover the real situation”,

Jinjikhadze explained.

The MDF fights the dissemination of fake news and myths in the Georgian media space through its ‘Myths Detector’ format. The aim of the organisation’s members is to react to disinformation and myths and provide the public with accurate, fact-based information.

The website mediachecker.ge is a platform for media critics in Georgia. The project is funded by the OSGF and implemented by the GCJE. The webpage actively disseminates information about materials containing disinformation and pro-Kremlin propaganda and highlights fake news and inaccuracies used to influence public opinion.

The 2017 NDI public poll confirmed that Kremlin propaganda regarding Russia’s military power has had a significant impact on Georgian society. According to the NDI survey, 41% of those interviewed believe that Russia’s military power is greater than that of the US, while 36% believe the US to be stronger militarily than Russia. Such a difference between these numbers is significantly influenced by regions populated with ethnic minorities. In these regions, 55% of those interviewed believe that militarily, Russia is stronger than the US.

Media-Literacy Projects

Representatives of NGOs believe that enhanced media literacy is closely linked with education, as society should be able to use it as an instrument to filter information and develop critical thinking.

‘I do not think that media literacy is an important factor, rather I believe the problem is in the level of education; media literacy can be one of its elements. In general, it is more important to raise the level of education and promote critical thinking”,

Levan Avalishvili, programme director of Institute for Development of Freedom of Information (IDFI), said.

Experts believe that media literacy should start in school and should be taught to pupils as a separate subject or in combination with others.

‘If media literacy is taught at schools, this will help the country’s development, especially vulnerable groups’,

the MDF director said.

There is no state programme supporting the development of media literacy in Georgia today, but there are media organisations working on this issue, e.g., on the margins of the media literacy programme with MDF elaborated guidelines that aim at assisting media consumers to check fake information and handle disinformation. The organisation, through the support of Deutsche Welle offers courses in media literacy, which include theoretical and practical instruction in the methods of countering propaganda.

On August 4, 2017, the Public Affairs Section of the U.S. embassy in Tbilisi invited Georgian non-profit/non-governmental organisations to submit proposals for a project lasting up to 24 months to improve media literacy skills among young Georgians between the ages of 16 and 24 that includes ethnic minorities and people at risk of being socially marginalised. Expected results included an increase of at least 20% in program participants’ ability to distinguish trustworthy news from fake news and an increase of at least 20% of those who cross-check information from the news.

On September 9, 2016, Georgian, Moldovan, and Ukrainian students participated in media literacy camps, which formed part of the Strengthening Independent Media project in Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine. While aiming to increase citizens’ access to reliable information about local, regional, and international issues of public importance through supporting the independent media sector, the project included components exclusively concerning young people: a media literacy camp and the ‘European Café’discussion club, organised at different venues all around Moldova, Georgia, and Ukraine. In total, 100 participants attended media literacy camps in the three countries, and feedback about the events was mostly positive. Programmes included topics such as: the basics of media literacy, how to develop critical thinking, practical mobile journalism, investigation of media effects, social media and blogging, and verification and fact-checking.

On March 12-13, 2017, as part of the EU funded project ‘Promoting freedom, professionalism and pluralism of the media’, the Council of Europe (CoE), in cooperation with the GNCC, organised a series of training seminars for the members of the GNCC based on CoE/European Court of Human Rights standards concerning the regulation of ‘TV products having detrimental effects on children’ and of ‘TV-like services’. During the training seminars, the CoE experts working at the European national communications commission, respectively in Poland and Bosnia-Herzegovina, reviewed the best European standards on how to ensure the protection of minors through legislation and self-regulatory mechanisms as well as specified programme labelling and age-rating practices. The experience of setting up the media-literacy networks and the role of the communications commission were also actively discussed during the events.

Conclusions

Based on our analysis, it seems right to say, in parallel to traditional military power, Russia resorts to the use of soft-power tools more and more often to support its foreign policy interests. These tools are being effectively used to spread the ideology and values of the Kremlin.

The Kremlin information machine influences media, political organisations, and civil society. The main source of Russia’s soft-power policy is the propagandistic, aggressive, anti-Western information campaign. In contrast to the pro-Kremlin propaganda, unbiased news agencies operating in the pluralistic media environment in Georgia with comparatively small resources cannot properly counter the massive disinformation flow. Kremlin propaganda has several pillars in Georgia. One of them comprises ultra-nationalistic movements, which are influenced by the Kremlin by manipulating issues of national identity. Russian disinformation has had a significant impact on the population of middle-aged and older people who lived in the Soviet era, can speak good Russian, and have economic and other links with people living in Russia. There are also serious challenges with regard to ethnic minorities. There is a need to strengthen and broaden existing policies and to optimise relevant mechanisms to fight disinformation. The language barrier is a serious factor in the regions, populated with ethnic minorities, as it exposes their vulnerability to disinformation and to their integration with the rest of Georgia.

A shortage of resources within regional NGOs and media also poses a problem. A lack of media literacy stands out as one of the main reasons pro-Kremlin propaganda spreads among the population. There is a serious problem developing the media skills of the population; however, the lack of media skills among journalists working in Georgia is far more important.

The majority of the population in Georgia supports the country’s European and Euro-Atlantic integration and the necessary reforms to achieve these goals. However, it should be noted that lately there has been a slight rise in anti-NATO feelings (2014, 15%; 2017, 21%). One of the main reasons for this trend could be the spread of pro-Kremlin propaganda.

The survey shows that the state lacks a clear vision to counter disinformation, proved by the fact that there is no national strategy to fight such threats. Pro-Kremlin disinformation has not been officially identified as a significant threat, which leads to suspicion that the threat is not duly assessed. Another problem is the ineffectiveness of cooperation between state bodies on this issue.

It is evident that myths are successfully spread in Georgian society. The types and form of these myths have been identified. They have been proven to be effective and efficient in spreading disinformation by delivering results. There are several non-governmental groups in Georgia that try to identify and decipher these myths. However, in an environment of asymmetric resistance, they are unable to tackle the problem fully.

Recommendations

- Recognise disinformation as a threat and develop a common vision—a strategy, to counter it.

- Increase cooperation between state bodies and support disseminating objective information (regarding the strategy).

- Introduce measures in the education system aimed at promoting media literacy. Media literacy skills should be taught at educational institutions, be they schools or higher education establishments, in combination with other subjects.

- Intensify coverage of issues related to European and Euro-Atlantic integration in the Georgian media space. The benefits to Georgia from this process should be explained in a way that is understandable to the population.

- Intensify Georgian and English language courses in regions populated with ethnic minorities.

- Support media organisations fighting disinformation and myths in order to expand the scope of their activities.

- Expand EU-related information campaigns targeted to ethnic minorities, e.g., meetings with small entrepreneurs who export their products to the EU market.