Introduction

The prospects for tighter economic integration with the EU have always been the glue keeping the Eastern Partnership together, disregarding existing political agenda differences. Therefore, it is not surprising that Joint Staff Working Document “Recovery, resilience and reform: post-2020 Eastern Partnership priorities” (JSWD) begins with prioritising resilient, sustainable, and integrated economies in the Eastern Partnership. Moreover, three of the Top Ten Targets and most country-specific flagman initiatives concern economic issues.

The economic cooperation agenda is extensive. The JSWD identifies four areas of cooperation within the priority of achieving resilient, sustainable, and integrated economies, namely:

- Trade and economic integration envisages strengthening the business environment and facilitating trade and investment, ensuring a level playing field, accelerating implementation of the deep and comprehensive trade areas (DCFTAs) with Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine, the Armenia-EU comprehensive and enhanced partnership agreement (CEPA) and other trade arrangements; concluding mutual recognition agreements of authorised economic operator programmes between the EU and partner countries; making efforts towards the interested partner countries’ accession to the Common Transit Convention; promoting good governance in taxation and taking the necessary steps to enable partner countries to join the Single European Payment Area.

- Investment and access to finance aim to achieve the first of the Top Ten Targets, namely providing support to at least 500 000 SMEs (20% of all SMEs in the region). Other goals include supporting structural reforms and fighting against corruption, and promoting equity and portfolio investments.

- Enhanced transport interconnectivity aims to achieve the second of the Top Ten Targets, namely that 3 000 km of priority roads and railways are built or upgraded in line with EU standards. Other goals include completing the network of common aviation agreements and improving land transport safety.

- Investing in people and knowledge societies aims to achieve the third of the Top Ten Targets, namely 70 000 individual mobility opportunities for students and staff, researchers, young people and youth workers. Other areas of cooperation include supporting modernisation and innovation at all levels of education and training and structured cooperation between EU and partner countries’ universities, VET institutions and youth organisations, supporting youth employment, employability, and entrepreneurship, and increasing each partner country’s position in Global Innovation Index.

These areas of cooperation have been complemented by country-specific flagship initiatives aimed at maximising impact and concentrate efforts on concrete priority projects. The Economic Investment Plan contains the following flagship initiatives aiming at resilient, sustainable and integrated economies in each of the partner countries:

- Armenia: Supporting a sustainable, innovative and competitive economy – direct support for 30 000 SMEs (Flagship 1). Boosting connectivity and socio-economic development – the north-south corridor (Flagship 2).

- Azerbaijan: Green connectivity – supporting the green port of Baku (Flagship 1). Supporting a sustainable, innovative, green and competitive economy — direct support for 25 000 SMEs (Flagship 3).

- Belarus: Supporting an innovative and competitive economy — direct support for 20 000 SMEs (Flagship 1), Improving transport connectivity and facilitating EU-Belarus trade (Flagship 2). These initiatives are indicative and subject to democratic transformation in Belarus.

- Georgia: Transport connectivity across the Black Sea — improving physical connections with the EU (Flagship 2). Sustainable economic recovery — assisting 80 000 SMEs in reaping the full benefits of the DCFTA (Flagship 3).

- Moldova: Supporting a sustainable, innovative, green and competitive economy — direct support to 50 000 SMEs (Flagship 1). Boosting EU-Moldova trade — construction of an inland freight terminal in Chisinau (Flagship 2). Improving connectivity — anchoring Moldova in the TEN-T (Flagship 4). Investing in human capital and preventing ‘brain drain’ — modernisation of school infrastructure and implementation of the national education strategy (Flagship 5).

- Ukraine: Supporting a sustainable, innovative, green and competitive economy — direct support to 100 000 SMEs (Flagship 1). Economic transition for rural areas — assistance to over 10 000 small farms (Flagship 2). Improving connectivity by upgrading border crossing points (Flagship 3)

The unprovoked and unjustified Russian full-scale war of aggression against Ukraine has created new dynamics in economic integration within the Eastern Partnership. Below we analyse the EaP economic integration trends in 2022, probably the most stressful year for the region in decades.

Methodology

This thematic brief is the fifth instalment in a series of studies conducted by the team of the project “Civic EaP Tracker: Monitoring EaP targets, deliverables and related reforms”, dedicated to the involvement of the EU in transformations in the countries of the Eastern Partnership.

The research group aims to examine various aspects of the situation in the countries and the reforms the EU actors in the target countries paid attention to, how they adapted their actions in this context to the new political, social, economic and security circumstances, as well as how consistent the countries were in implementing reforms in response to Brussels’ reactions.

For this purpose, data were collected on statements by European officials, official conclusions regarding the implementation of policies by EU institutions, including the decisions envisaging a deeper integration into the EU market, and changed or newly established support mechanisms (programs, projects and funds), the addressees of which were partner countries. Information was also collected on the laws and other legal acts adopted in the Eastern Partnership states and steps in their implementation related to the priorities of the “Joint Staff Working Document – Recovery, resilience and reform: post 2020 Eastern Partnership priorities”. The analysis covered all the significant events of 2022 in this context.

The study has a common framework for Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine. Due to the de facto termination of the participation of Belarus (captured by a self-proclaimed authoritarian regime) as a state in the Eastern Partnership, the study does not include Belarus.

This thematic brief is devoted to the processes in the priority area “Together for resilient, sustainable and integrated economies”. Accordingly, all the analysed information about the actions of the EU and reforms in the partner countries was related to the issues of this chapter of the Joint Staff Working Document. The key analysed topics include market access, technical barriers to trade, access to finance, transport connectivity, personal mobility, and education.

Main trends in the economic integration field of the Eastern Partnership region

The Russian war of aggression in Ukraine has triggered significant changes in the trade landscape among the EaP countries, as well as their trade with the EU and the rest of the world.

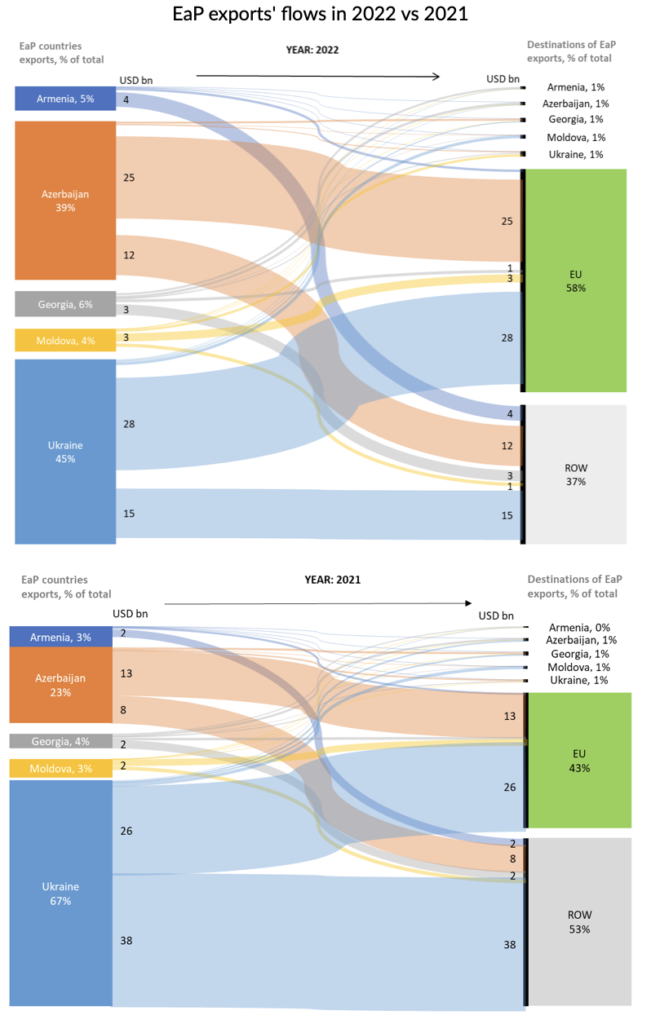

The economic links between the EaP counties and the EU have strengthened. In 2022, the EU’s share as the export destination for the EaP countries reached 58% compared to 43% a year before, although the aggregate EaP exports stayed close to USD 98 bn in both years. The export reorientation to the EU was driven by multiple factors, including new logistic routes due to the blockade of Ukraine’s seaports by Russia, active EU measures to support Ukraine’s and Moldova’s exports and new energy policy, aiming to reduce dependence on Russian fuels that helped Azerbaijan.

EaP exports’ flows in 2022 vs 2021

Source: UN Comtrade; EaP countries excluding Belarus

The analysed five EaP countries can be tentatively split into two groups based on their export orientation to the EU.

The first group includes Azerbaijan, Ukraine and Moldova, for which the EU was the dominant destination in 2022. Among these countries, Ukraine experienced the most significant change. In 2022, Ukraine’s exports to the EU reached 63% of the country’s total for the first time, compared to 39% the previous year. Moreover, the export value to the EU slightly increased, despite an overall drop in total goods exports by about one-third.

The second group consists of Armenia and Georgia, where exports to the EU accounted for 15% of the each country’ total, and the relative importance of the EU as an export destination decreased compared to 2021. Instead, the countries boosted exports to other destinations, particularly Russia.

Noteworthy, the exports dynamics within the EaP region remained low, increasing by only one percentage point between 2021 and 2022. Georgia and Moldova were the only two countries with a noticeable role in exports to other EaP countries: Georgia shipped to Armenia and Azerbaijan, while Moldova to Ukraine. So, as before, exports featured a ‘spike and hub’ structure, with the EU gaining further importance.

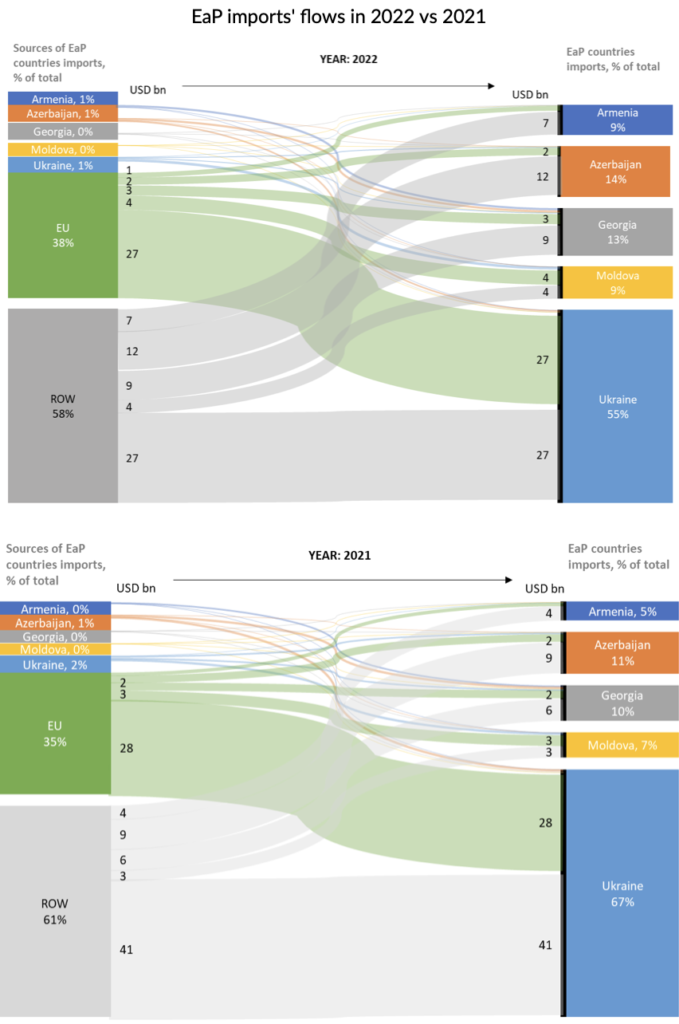

In terms of imports, the trends were similar but far less pronounced compared exports. The EU has somewhat increased its significance as a source of imported products for the EaP countries, but the increase was much smaller: from 35% in 2021 to 38% in 2022. However, this increase occured amidst the substantial rise in the EaP total imports, to USD 101 bn in 2022 compared to USD 70 bn a year before.

The role of Ukraine as a source of imports halved to 1% of the total imports, while overall, the EaP countries sourced only 4% of the total imports from other EaP states. Armenia and Azerbaijan bought over 80% of imports outside the EU and the EaP countries, while Ukraine and Moldova relied on the EU, with approximately half of their exports originating from the EU countries.

Thus, in terms of imports, the EaP countries relied on the EU much less than in terms of exports. But still, they were buying products mostly outside the EaP.

EaP imports’ flows in 2022 vs 2021

Source: UN Comtrade; EaP countries excluding Belarus

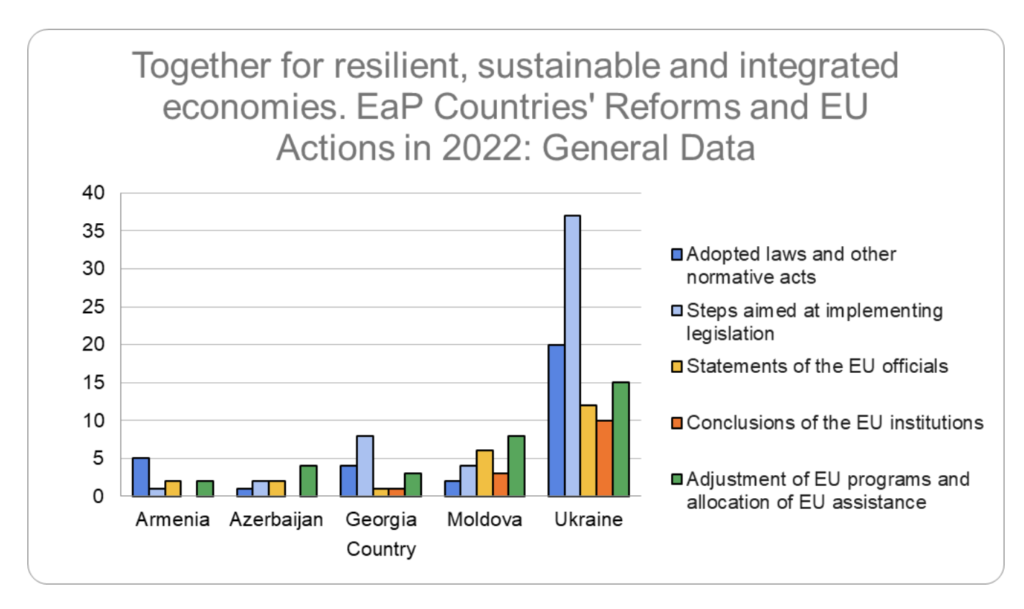

The analysis of the EaP countries’ reforms and the EU actions provide further insights into the changes in structure of trade in goods in 2022, namely the increase of the relative importance of the EU as the EaP trade partner, with the incredibly intense links between the EU and Ukraine.

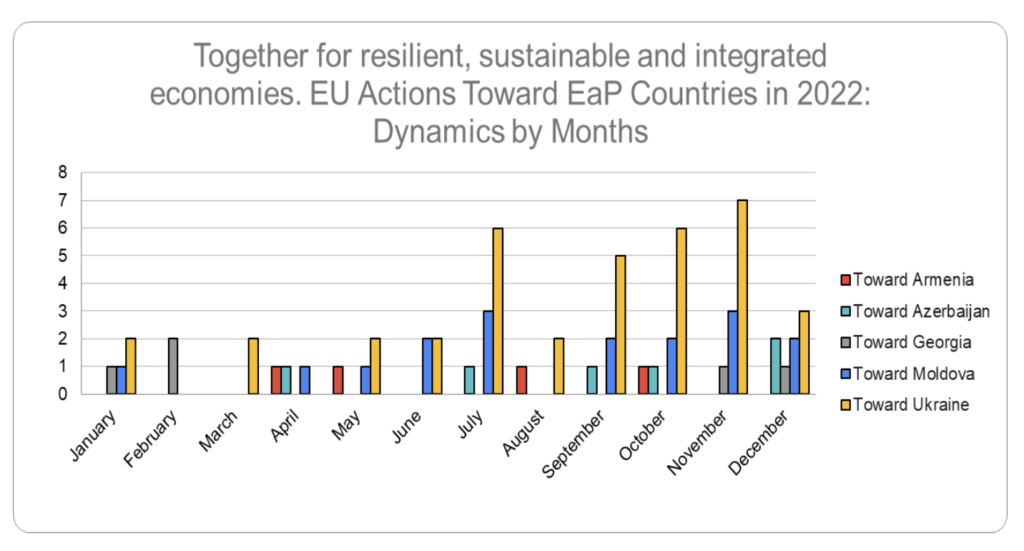

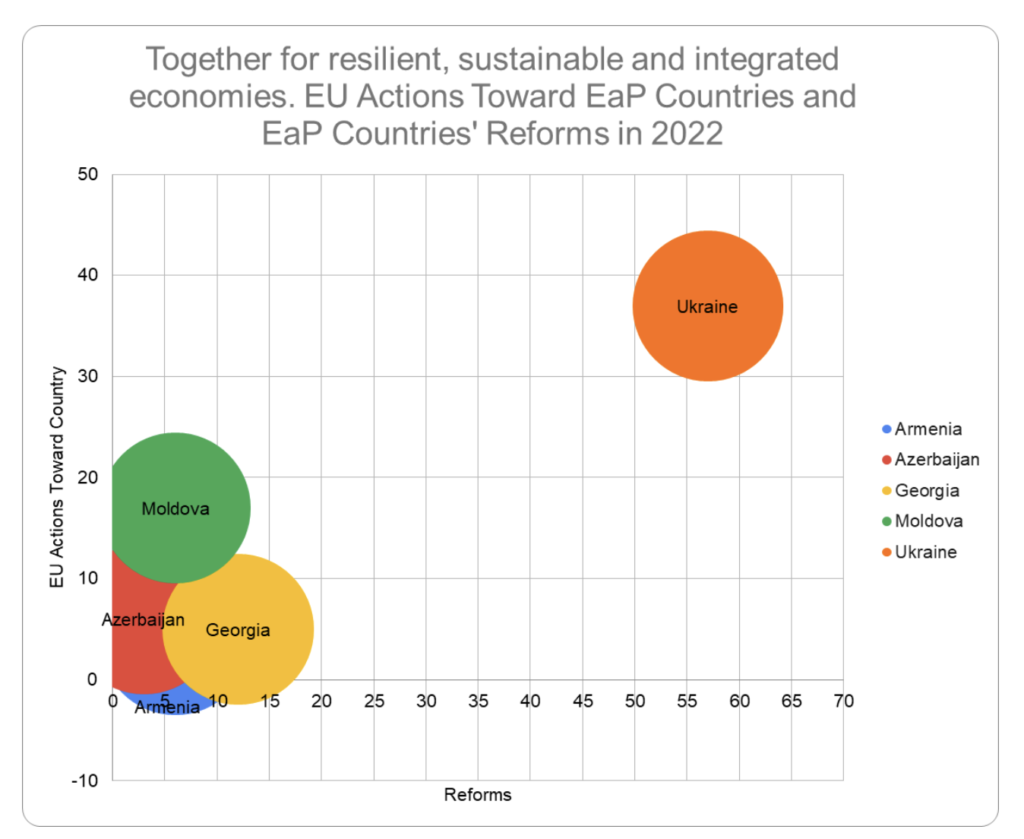

In 2022, the EU and the EaP countries took decisions to bring the countries closer to resilient, sustainable and integrated economies, but the intensity of cooperation varied significantly among the countries. Out of the 153 events listed in the database, Ukraine reported 61%, Georgia and Moldova 11% and 15%, respectively, and Armenia and Azerbaijan – about 6% each. This striking discrepancy should be attributed, at least partly, to the varying challenges faced by the region’s individual countries and their political interests.

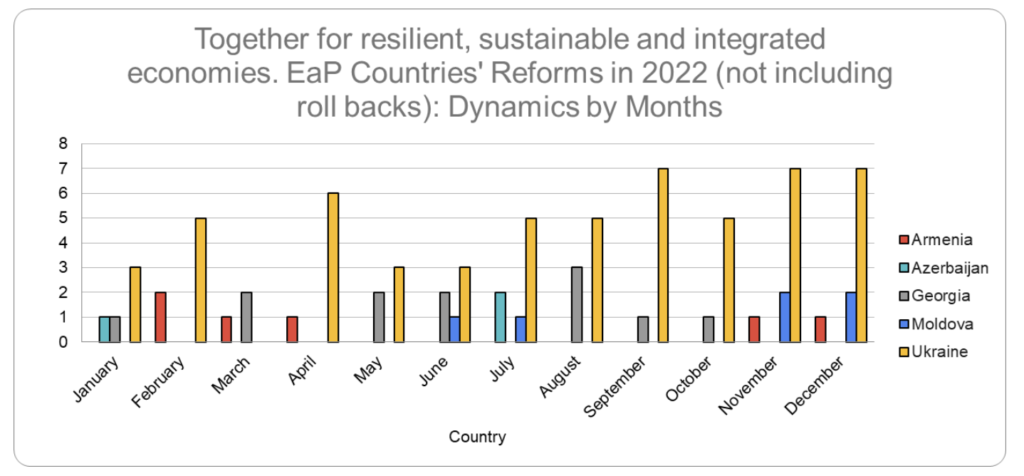

Let’s first consider the reform efforts undertaken by the countries. Our database contains 84 reforms registered in 2022, of which Ukraine reports two-thirds.

Ukraine is leading the reform process among the EaP states. Although the reform intensity increased in the second half of the year, the only month without reforms in Ukraine was March, de facto the first month of the full-scale Russian military aggression. The average observed’ speed of reforms’ was almost five events per month, including adopting new legislation and developing secondary legal acts and other implementation steps.

The critical legal revolve around the intensive development of legislation related to food safety, animal welfare and other related spheres. Ukraine adopted laws on materials and objects intended to be in contact with food, on improving state regulation in handling pesticides and agrochemicals and on bringing legislation on the protection of rights to plant varieties and seed and seedling production in line with the provisions of the legislation of the EU, as well as many related secondary bylaws.

The second sizeable legislative activity was related to the accession to the EU common transit system in October 2022. To prepare the legal foundation for this decision, Ukraine acceded to the Convention on the Common Transit and the Convention on Simplification of Formalities in Trade in Goods and introduced changes in other customs-related legislation. Noteworthy, these steps are implementing one of the areas of priority cooperation envisaged in the EaP JSWD.

Another essential legal activity was the adoption of multiple laws related to the labour market, including regulating labour relations with non-fixed working hours, strengthening the protection of employees’ rights and optimising labour relations.

Ukraine also adopted a long-awaited law on postal communication, unblocking the progress in EU integration of the sector, for which the Association Agreement with the EU envisages internal market treatment.

Georgia reports the second-highest speed of reforms among the EaP countries, with one reform per month. The key changes encompass several spheres. Firstly, Georgia has been working on aligning its technical regulations with the EU norms, considering recent changes in the EU acquis. The adoption of the law on consumer rights protection is also interlinked with product safety reforms. These activities aim to implement the EU-Georgia Association Agreement, thereby contributing to the EaP JSWD implementation.

Another important step, fully aligned with the JSWD priorities, is that the draft laws regarding amendments in the legislation for joining the Single Euro Payment Area were passed to the Georgian Parliament for approval.

In January 2022, the new law on entrepreneurship entered into force in Georgia. It introduced numerous innovations and changes, bringing Georgian corporate regulation closer to the EU norms in line with the EU– Georgia Association Agreement.

Moldova and Armenia share the third place in terms of the reported ‘reform speed’, adopting or implementing one reform every two months on average in 2022.

In Moldova, the critical legal changes focused on improving the business environment. The laws on zones of free enterprise and organisation and functioning Public institution “Organization for Entrepreneurship Development” (OED) were passed, complemented with the secondary legislation. The OED legislation aimed to conform the OED corporate governance to the best practices, taking into account the principles of corporate governance developed by the OECD, the recommendations of the European Parliament and the European Commission regarding corporate governance in financial institutions, the national regulatory framework regarding the organisation and operation of public institutions, and the recommendations of the World Bank and other international experts.

Armenia has focused its reform efforts on education, with the law on public education passed in February 2022. The law introduced new Government standards and programs for the public education sector and envisaged the modernisation of state education facilities and management systems of public educational institutions. The voluntary certification of teachers, linking their salaried with the confirmed qualifications, was introduced. In November, Armenia adopted the state program for the development of education in the Republic of Armenia until 2030.

Azerbaijan was the least active, reporting only one reform per four months. The critical change was the adoption of the Strategy of socio-economic development of the Republic of Azerbaijan for the period 2022-2026 in July.

Now let’s analyse the EU’s actions towards the EaP states. Our records indicate a total of 69 actions, mostly statements, EU program adjustments and allocations. Slightly more than half of the action were related to Ukraine, but here we see disproportionally higher number of conclusions, i.e., specific decisions allowing deeper integration. Noteworthy, the intensity of the EU decisions increased in the second half of the year.

In June 2022, the EU took the ground-breaking decision regarding Ukraine and Moldova by granting them the candidate status and thereby setting the region’s new – and much higher – integration benchmark. Georgia, which also applied, received the potential candidate status. At the same time, Armenia and Azerbaijan’s’ appetite’ for deeper economic integration integrating with the EU beyond existing agreements seems much lower, although for different reasons. Armenia is a member of the Eurasian Economic Union, the customs union dominated by Russia, while Azerbaijan is still not a WTO member.

The full-scale Russian war of aggression in Ukraine has triggered a series of EU actions aimed at supporting Ukraine’s exporters and the economy in general by providing better access to the EU market, in some cases temporarily. In May, the EU eliminated tariff rate quotas and other remaining tariff barriers on exports to the EU for a year, while in July, a temporary road transport agreement was signed, removing road permits for cargo transport. Earlier in March, the EU extended the coverage of the Temporary Protection Directive to include Ukrainian individuals. That granted displaced people fleeing the war in Ukraine the rights to work, education, social benefits, and medical care in the EU.

As for more durable integration steps, the EU launched the Solidarity Lanes initiative. Its priorities included additional freight rolling stock, vessels and lorries; capacity of transport networks and transhipment terminals; facilitated customs operations and other inspections; and provision of storage of goods on the territory of the EU as the short-term steps. In the medium to long term, the EC aimed to work on increasing the infrastructure capacity of new export corridors and establishing new infrastructure connections as a part of the reconstruction of Ukraine. The tasks embedded in the Solidarity Lanes are closely aligned with the connectivity tasks of the EaP JSWD. As mentioned above, in October 2022, Ukraine joined the European Common transit system.

Yet another critical dimension of Ukraine’s integration into the EU was joining several more EU programs. The country became a participant in the Customs Cooperation Program and the Tax Cooperation Program Fiscalis in September. In July, the EC announced the extension of four European Transport Corridors to the territories of Ukraine and Moldova.

Ukraine has also received extensive financial assistance from the EU to address fiscal needs and some immediate rebuilding efforts. The EU provided EUR 7.2 bn of Macro-Financial Assistance to Ukraine in 2022, while the EBRD and EIB expanded their loan facilities to support business activities in the country.

Moldova ranked second in terms of the EU actions after Ukraine. Apart from the revolutionary decision about granting the candidate status, Moldova has also attracted assistance to address the negative economic shock related to the full-scale Russian military aggression against Ukraine. In July, the EC adopted temporary trade liberalisation measures for Moldovan agricultural products that are not fully liberalised by expanding duty-free tariff rate quotas. Moldova has also attracted several necessary infrastructure loans for the reconstruction of roads and road safety improvement.

The EU actions regarding South Caucasus countries were much less intensive compared to Ukraine and Moldova. For Georgia, the most prominent decisions were the launch of several projects like EU4Digital and EU4ITD – Catalysing Economic and Social Life in Pilot Integrated Regional Development Programme (PIRDP) Regions. Also, Georgia, alongside Ukraine and Moldova, became an affiliate member of CEN/CENELEC, the EU product standardisation organisations.

In Azerbaijan, the EU focused on new versatile initiatives, primarily focusing on new business and educational opportunities. For example, in September 2022, the first-ever investment project co-financed by the Eastern Europe Energy Efficiency and Environment Partnership (E5P) fund in Azerbaijan was signed. In December, Azerbaijan and the EU signed a Memorandum of Understanding to develop the Black Sea Energy submarine cable. The eTwinning project aimed at at fostering improved communication with European schools began.

For Armenia, the EU’s actions primarily focused on financial assistance. In August, the EU approved disbursements of EUR 14.2 million in grants for two budget support programmes – Support to Justice Sector Reforms in Armenia and The Covid-19 Resilience Contract for Armenia. In October, the EU announced EUR 300,000 in emergency aid for conflict-affected people in Armenia.

Conclusions and recommendations

Both reform efforts of the EaP countries and the EU actions reveal very different interests in economic integration within the region. This interest depends on the country’s current political and economic circumstances and long-term integration aspirations.

Ukraine is on one end of the spectrum. The country is keen to achieve EU membership fast, thus it is active in reforms despite the war and demanding/expecting a similarly proactive EU position. Closer trade links with the EU observed in 2022 result from not only the Black Sea logistic constraints but also the deliberate policy actions aiming to promote Ukraine’s economic integration into the EU market as a mitigation tool against the consequences of Russian aggression. It is expected that the economic integration maintains the speed or even accelerate.

Azerbaijan and Armenia represent the other end of the spectrum, featuring limited reforms and limited EU actions. Though, there are important nuances. For Azerbaijan, the EU is the largest export destination, but the export structure is heavily biased towards mineral fuels, a very peculiar commodity. Azerbaijan is interested in developing business initiatives, infrastructure projects, and training. However, the country has no integration ambitions. Thus, the existing level of cooperation is expected to remain in place.

Armenia has more elaborated trade relations with the EU, as the parties signed the Armenia-EU Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement (CEPA), and its implementation is among the EaP JSWD priorities. However, in 2022, Armenia’s export links with the EU somewhat weakened, as the country has become much more oriented on shipments to Russia. The EU actions in Armenia focused on financial assistance, predominantly needs-based rather than reform-driven.

Georgia and Moldova are in the middle but far less active than Ukraine. Moldova was the recipient of quite intensive EU actions while conducting limited reforms itself in 2022. And vice versa, Georgia has been more involved in reforms, driven by the Association Agreement implementation, but got less attention from the EU.

Considering the findings and trends of 2022, the following recommendations can be offered to EaP governments and relevant EU actors:

- To continue implementing a “more-for-more” approach, whereby the EU provides timely rewards for active reformers. The Association Agreements and DCFTAs implementation offers a positive progress path alongside a more sophisticated and, thus, slower accession process.

- To invest more in transport connectivity. The ongoing war of aggression highlighted significant transport and logistics constraints within the region. In 2022, several important initiatives were launched to address these challenges, and they must be fully implemented to alleviate the existing physical restrictions on trade.

- To pay more attention to SME development in the region. The improvement of the business environment, access to finance, and SME support are crucial targets for the EaP JSWD. At the same time, the analysis revealed that SME-focused actions were limited in all countries.

- To develop and implement a monitoring system for annual measuring the level of achievement of post-2020 priorities proposed by the JSWD. This instrument could become helpful in avoiding/preventing further disparities within the EaP region in terms of the level of political commitment and intensity of internal activities on the way to resilient and sustainable economic integration.

SPECIAL VEW FROM BELARUSIAN CIVIL SOCIETY

Reality check for Belarus on EaP priority “Together for resilient, sustainable and integrated economies”

Belarus remains a laggard in terms of its structural transformation and conducted only limited economic reforms since the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The government has been slow to implement a reform agenda, focusing instead on stability and continuity as a background of Lukashenka’s regime propaganda. The only visible attempt of reform in the recent eight years was the macroeconomic stabilisation. The country’s economic crisis in 2015-2016 finally nudged the government to commit to macroeconomic stabilisation in its monetary and fiscal policies. The National Bank of Belarus abandoned the fixed exchange rate and planned a transition to inflation targeting since late 2010s. The government in mid 2010s limited soft budget constraint for state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Trade (without integration) with the EU and EaP countries remained on the wish list of the Belarus’ authorities to drive export and contribute to economic growth. Trade between Belarus and the EU, and Belarus and EaP countries (mostly, Ukraine) grew significantly (ca.70%) in 2021 and early 2022 as a response to post-COVID recovery and attempts of Belarusian sanctioned companies to maintain trade with the EU via EaP countries despite EU sanctions.

However, political turmoil since late 2020, increasing sanctions, and new wave of political and economic isolation after the start of war in Ukraine discharged previous achievements in reforms and trade. Investment in the less efficient SOE sector resumed since 2021, often at the cost of more public debt, decreased macroeconomic stability, and the loss of the benefits of competition, while at the same time not enabling sustained growth. Administrative price control instruments were used to fight growing inflation. The position of the private sector remains tenuous: the manufacturing sector has never been privatised, and remaining sectors compete heavily with SOEs, which produce over half of Belarus’ GDP. In the 2010s, the average GDP growth rate of was 0.9 % per annum, while income divergence with its more successful neighbouring countries (e.g., Poland, Lithuania, Latvia) created migration pressures. The war in Ukraine brought even more economic pressure for Belarus. The new wave of migration led to up to 150 thousands Belarusian migrants in the EU and over seven thousands of new companies with Belarusian beneficiaries registered the EU. In terms of trade structure, Belarus is getting more and more dependent on Russia, as its share in Belarus’ export grew from 41% in 2021 to 57% in 2022. Belarus’ export to Ukraine completely stopped.

In the current legal and political framework, EaP economic priority seems barely feasible for implementation inside Belarus. Trade and economic integration as well as investment are impossible due to economic sanctions and will predictably stagnate over time unless sanctions are lifted. Other dimensions for the activities within the economic domain of EaP priorities (access to finance, enhanced transport interconnectivity, and investing in people and knowledge societies) are significantly limited inside Belarus and often available for increasing Belarusian diaspora in the EU countries. Yet some of those dimensions remain of critical importance for independent Belarusian actors and Belarusians in general and should stand in order to: a) serve as a goal and a part of economic recovery plan for independent Belarusian actors when democratic changes will take place, and b) serve as a potential goal and opportunities for Belarusians that remain inside the country.

The EU could prioritise communication/cooperation with the independent Belarusian civil society the economic issues that correspond to the above two strategic aims, and made of:

- As a goal and a part of economic recovery plan for independent Belarusian actors:

- Framework and process of potential economic integration after democratic elections

- Better access to finance, including blending and guarantees, for SMEs outside Belarus

- Investing in cyber resilience programs and digital government transformation that can be implemented right after the democratic changes in the country.

- As a potential goal and opportunities for Belarusians that remain inside the country:

- Increasing mobility for people from Belarus to the EU countries, including visa facilitation and resuming flights to/from Belarus

- Investment in environment and climate resilience programs and initiatives, including energy efficiency initiatives inside Belarus undertaken by independent actors

- Investment in human capital development, including higher education exchange programs, vocational training in the EU, and visits of EU professionals to Belarus.

The experience of PACE shows that official authorities from Belarus might and should be replaced by the representatives of the democratic actors as it concerns participation in official EaP meetings.