Moldova’s security sector went through a prolonged period of a stagnation due to the political disengagement. Furthermore, the President in his October interview stated that Moldova as a neutral country does not require a national Army at all. But the 2014 Russian intervention in Ukraine was actually a wake-up call to rethink the security policy. However, the road to transformation was characterized by a series of disagreements between the key state institutions. The upcoming Parliamentary elections in 2018 will be yet another factor of uncertainty for Moldova and its partners as neither the governing coalition, nor the opposition parties presented a coherent security vision so far.

Understanding Moldova security sector

Understanding the Moldovan security sector is impossible without first recognizing the primary motivation behind the policy and decision making. As in the majority of countries with a hybrid political regime, the act of governance is largely subordinated to the private interest. Several political actors compete for the state resources. The defence sector was a low priority in the political competition as it provided little political, economic and reputational incentives. In Moldova there is no consolidated military establishment capable of pushing its own agenda, therefore the Ministry of Defence was a marginalised institution from the political perspective. Additionally, Moldova does not have a defence industry capable of generating the economic incentive to invest in the Armed Forces. The little of what remained from the industrial complex during the Soviet Union, was located in the Transnistria region which the Moldovan authorities lost control of after the 1992 conflict.

As a result, the Moldovan political establishment was largely disengaged from the defence sector. It was satisfied with a passive security policy based on the principles of neutrality because it required little effort to maintain, despite providing no security benefits whatsoever in its current form. Consequently, the Moldova defence sector was heavily under-resourced, the defence budget varied between 0.3-0.4% of the GDP , by far the lowest in the Eastern Partnership countries.

It is especially bothersome if taking into consideration the Transnistria “frozen conflict” which remains one of the main security challenges for Moldova. The wake-up call came in 2014 when the Russian Federation intervened in Ukraine by deploying a new type of the hybrid capabilities.

It is especially bothersome if taking into consideration the Transnistria “frozen conflict” which remains one of the main security challenges for Moldova. The wake-up call came in 2014 when the Russian Federation intervened in Ukraine by deploying a new type of the hybrid capabilities.

Moldova security policy post-Maidan

The 2014 Russia-Ukraine conflict profoundly affected the Moldovan national security changing the threat perception among the policy and decisions-makers. It highlighted three core changes: (1) the threat of a direct foreign intervention came back as a major security concern; (2) the intervention is hybrid in nature and countries proved to be unprepared to counter it; (3) the Eastern Partnership countries have deeply-rooted security vulnerabilities that enabled these types of foreign interferences.

With these three assumptions in mind, the Moldovan authorities needed to rethink its security policy and accelerate the defence sector reform. As a result, in 2014 along with Georgia and Ukraine, Moldova negotiated a new NATO assistance package – Defence Capacity Building Initiative (DCBI). The DCBI was split into two phases: in the first one it required an update of such strategic documents as the National Security Strategy, the National Defence Strategy and the Military Strategy, and in the second one, the NATO would provide its assistance in transforming the Moldovan armed forces.

The actual implementation of the DCBI package was hampered by the domestic political crisis (2015-2016). As a result, the strategic documents were not adopted, the security sector reform halted and no significant actions were taken to strengthen the country resilience. Furthermore, as the echo of the Ukrainian conflict subsided and further escalation contained, the Moldovan political establishment reverted back to a passive security policy. The election of a pro-Russian opposition President Igor Dodon in November, 2016 gave an excellent pretext to shift the attention to the internal power struggles.

President Vs. Government. Implications for the security sector

It is worth noting that despite the apparent incompatible political attitudes between Igor Dodon and the Governing coalition, these actors do not have a fundamental disagreement in term of the security policy, both largely adhering to the principle of the state neutrality. The divergence stems primarily from the political positioning and foreign policy preferences: on the one hand, a pro-Russian President, on the other hand, a pro-European Government backed by a Parliamentary majority. The situation is complicated by the fact that in the framework of the Moldovan institutional setup, the President is an influential security actor. When his agenda collide with that of the Government it creates major disruption for the security sector. This is exactly what happened in Moldova throughout the 2017. Initially the institutional divergence were held at the level of rhetoric, but escalated gradually to generate an institutional deadlock in autumn of this year.

The first considerable disruption for the security sector was the dismissal of the Defence Minister appointed by the governing coalition – a move tacitly approved by all stakeholders. The ministry lacked a key leadership figure for more than ten months which considerably weakened the institution and rendered it incapable of the efficiently promoting the reform agenda.

Both the President and the Governing coalition both largely adhere to the principle of the state neutrality

The second disruption was the withdrawal of the National Security Strategy, prepared by the previous President administration. It was a key policy document developed in the framework of the Defence Capacity Building Initiative, and its withdrawal slowed down the development of other strategic documents. The Government paid very little attention to this matter, largely because the political establishment was preoccupied with other issues.

The third disruption concerns the President refusal to approve the Moldovan troops participation in the international military exercises . It became a considerable irritant in the bilateral relationship with two of the Moldova leading defence partners – USA and Romania – who urged the Government to intervene, resulting in the first public conflict between the institutions. The Government overthrew the President interdiction and approved the troops participation in the military exercise. Furthermore, the President lost the legislative battle in the Constitutional Court which effectively undermined his authority.

The forth disruption, with the most public resonance, involves the appointment of the Minister of Defence. The President blocked twice the Government nominee, even after a repeated vote in the Parliament, triggering an institutional deadlock. The Government overcame it by appealing to the Constitutional Court which came up with an innovative solution to the problem. The Court decided to temporary suspend the President and designate an incumbent (in this case the President of the Parliament) for the single task of appointing the new Minister.

This measure is a part of a larger effort by the governing coalition to undermine the President as a security stakeholder. Just before Igor Dodon taking office, the President was stripped of the control over two key institutions: the State Protection and Guard Office placed under the Government control, and the Information and Security Services (the national intelligence agency) placed under the Parliament control.

Consistently losing its authority over the security sector, the President adopted a more confrontation tone towards the Government and the defence institutions. In his recent interview to the Nezavisimaya Gazeta (The Independent Newspaper), he stated that Moldova as a neutral country does not require a national Army. It was an uncharacteristic claim for Igor Dodon, especially taking into consideration that the Armed Forces are the second most trusted institution in Moldova after the Church. In terms of its policy impact, the President rhetoric is indicative of the frustration over the recently lost political battles rather than an outline of the actual security policy he would pursue in the future.

Future prospects on Moldova security policy

The confrontational tone between the President and the Government reflected negatively on the security sector, nonetheless, there are some developments to look forward too. Soon after the Minister of Defence took its office, the Government approved the National Defence Strategy (NDS) designed to set up the policy framework for a new cycle of the defence planning. The strategy focused on the hard and hybrid security issues such a presence of the Transnistria paramilitary forces backed up by the Russian troops, information and cyber threats, protection of the critical infrastructure, fight against terrorism and control of illegal migration. In terms of the regional security, the strategy aims to deepen the partnership with the EU and NATO, and seeks out to expand the security cooperation with Romania, Ukraine, and United States. It also addressed the critical issue of the inadequate funding for the defence sector. The NDS initially envisaged a two-stage rise of the defence spending to 0.5% of GDP until 2020, and a gradual increase to an the European average of 1.4% of GDP after that.

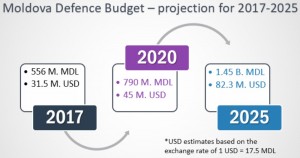

After the consultation with the Ministry of Finance, the final formula was agreed. The current defence budget of $31.6 mln (0.4% of GDP) should increase to $44.9 mln by 2020 and to $82.4 mln by 2025 (0.52% of GDP adjusted for the project GDP growth). Contrary to the President Dodon statement, Moldova does require a better equipped and more prepared Army to deal with the new challenges that the country faces today.

After the consultation with the Ministry of Finance, the final formula was agreed. The current defence budget of $31.6 mln (0.4% of GDP) should increase to $44.9 mln by 2020 and to $82.4 mln by 2025 (0.52% of GDP adjusted for the project GDP growth). Contrary to the President Dodon statement, Moldova does require a better equipped and more prepared Army to deal with the new challenges that the country faces today.

When it comes to the actual implementation, Moldova has a habit of writing good strategies on paper with a poor further implementation. The soon-to-open NATO Liaison Office (NLO) in Chisinau may provide just the necessary amount of the encouragement. The Office goal is to deepen the political dialogue and provide tailored assistance in reforming the defence sector. Even though it is a step forward in the Moldova–NATO partnership, further cooperation will be built with much caution, taking into consideration a generally negative public attitude towards the Alliance and the possible change of the political landscape after the 2018 Parliamentary elections with the possibility of Igor Dodon and the Socialist Party forming the new government.

Speaking about the President, after withdrawing the previous draft of the National Security Strategy in June, 2017 the Supreme Security Council, a consultative body for the Moldovan President, embarked on developing a new one by the end of 2018 . It is difficult to ascertain its content as Igor Dodon did not present a detailed outlook of his security vision, being primarily engaged in the anti-Western rhetoric. From what can be gathered from the public speeches, he firmly stands by the principle of the permanent neutrality and is set to keep Moldova out of any military alliances. However, it is uncertain whenever he intends to actually scale back the cooperation with NATO and other Western partners, as their support is essential in maintaining at least a minimal level troops preparedness by participation in the military exercises and the international peace keeping operations. Furthermore, the Euro-Atlantic community is the main development partner whose support Moldova cannot afford to lose regardless of the party or a leader in power. Another key partner for Moldova is Romania which the President has a special relation to. On numerous occasions, he singled out the Unionist movement as one of the core national threat, but whenever his view will materialize in an actual policy still remains to be seen. Any attempts to ban it at the official level will most likely strengthen the movement and considerably damage the relations with Romania.

Igor Dodon partnership portfolio with Russia does not mention any defence cooperation, and it is safe to assume that no such initiative will emerge in the near future

In contrast, Igor Dodon partnership portfolio with Russia does not mention any defence cooperation, and it is safe to assume that no such initiative will emerge in the near future. At the same time, Russia is a key stakeholder in the Transnistria conflict settlement as it holds a strong influence over the region in the political, economic and security terms. The Moscow’s ideal expectation of Transnistria is to reintegrate it in Moldova on the principle of federation with a far reaching autonomy in order to obtain a direct leverage over the Moldovan policy-making, creating in the process an international precedent to solve the other similar conflicts in the post-Soviet space. The necessary premises to achieve this goal may come during the next Parliamentary elections in 2018. However, the chances that the President and his Socialist Party will immediately deliver on this promise is rather slim because they will have first to compete over the control of the state institutions, secondly to overcome a public pushback from the pro-European electorate, and thirdly deal with the pressure from the international partners. Under these circumstances, the most-likely course of actions is the preservation of the current status quo which suits all the stakeholders. It also includes little chances of withdrawing the Russian troops from the territory of Transnistria, especially with the half-hearted efforts by the Moldovan Government so far.

What is required at a regional level is to improve the solidarity among the Eastern Partnership countries, in particular those with the pro-European aspirations. In the case of Moldova, the radical change of the Ukrainian approach to the Transnistria conflict shifted the momentum of the settlement process in its favour. The same results can be reproduced by the other EaP countries, if the policy makers develop joint projects to improve the resilience, and support each other during the crisis.