Romania presents a case of balanced approach of using hard and soft security measures in forming its system of resilience to possible Russian aggression on various fronts. Although in hard security issues NATO remains the cornerstone of its resilience, in energy and informational sphere was able to develop its own capabilities – both legislative and practical. Still some additional measures should be considered in the sphere of state cooperation with civil society and within closer links with allies in terms o f new regional security projects.

Author:

- Oleksandr Kraiev, North America Studies Program Director, Foreign Policy Council “Ukrainian Prism”

Reviewer:

- Dorin Popescu, President and Founding Member of the Black Sea House Association

Editor:

- Hanna Shelest, Security Studies Program Director, Foreign Policy Council “Ukrainian Prism”

Contents

- Vulnerability in Hard Security

- Economic Vulnerability

- Informational Vulnerability

- Cases of Successful Operations to Detect and Limit Russian Influence and Manipulation

- The Threat of Reflexive Control Operations

- Recommendations

Vulnerability in Hard Security

Romania is showing significant level of resilience when speaking within the hard security sphere, although main part of this resilience comes from its enhanced cooperation with its allies. Romania’s armed forces are currently entering a new phase of strengthening and restructuring. The government just recently presented an updated National Security Strategy 2020-2024, according to which security conditions and threats of a new type are forcing Romania not only to expand and co-finance its own defence forces but also to look for new ways to adapt to these conditions.

In the press release (issued 1 March 2022), Romanian President Klaus Iohannis stressed the need to strengthen “containment and defence positions on the eastern flank” in the future. He repeated the same thesis on March 11 during a meeting with US Vice President Kamala Harris in Poland. Iohannis acknowledged that “security starts at home”, so Romania has committed itself to strengthening the transatlantic strategic partnership by strengthening defence measures.

As early as December 2021, the Romanian parliament approved a decision to strengthen the country’s military capabilities by increasing the defence budget to 25.9 billion lei (USD 6 billion), which ultimately reached 2% of GDP – the threshold of military spending set by NATO. Romania’s military budget for 2022 is about 55% higher than in 2016. In addition, it recorded an annual nominal increase in military spending of 14% compared to 2021. Nevertheless, the new security situation caused by aggression required additional economic interventions.

In recent years, official Bucharest’s defence investments have focused on tracked and wheeled armoured vehicles, missile systems, and new aviation development programs. Following such military programs, Romania plans to purchase 32 F-16 aircraft from the Royal Norwegian Air Force to supplement its fleet. In addition, Romania is also seeking a Patriot air defence missile system and a HIMARS high-mobility missile system from the United States. Finally, Shepard News noted that an additional budget for the Romanian military sector could help revive the Romania-Rheinmetall Agilis armoured car program, which is currently paralysed by a stalled procurement plan.

Bucharest sees NATO membership as a key element in its security. Today, Romania is one of the key states supporting security and stability on NATO’s Eastern flank. Romania’s areas of responsibility in the Black Sea region include air reconnaissance, patrolling and supporting the Alliance’s infrastructure capabilities. The multinational brigade in Craiova, for which Romania is the host country, forms a land component of the Alliance’s advanced presence in the east. So far, ten allies – Bulgaria, Canada, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, and Spain – have committed themselves to assisting the brigade headquarters in its work and coordinating enhanced staff training. Definitely, the presence of NATO bases and troops on Romanian territory intensively contribute to hard security resilience of Romania.

Following Russia’s unprovoked and unjustified invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the Allies sent additional ships, aircraft and troops to NATO territory in Eastern and South-Eastern Europe, further strengthening the Alliance’s deterrence and defence. This includes thousands of additional troops to NATO battlegroups, fighters to support NATO air police missions, strengthening the n aval forces in the Baltic and Mediterranean Seas, and increasing the readiness of troops to the NATO Response Force. At the extraordinary NATO summit in Brussels on 24 March 2022, the Allied Heads of State and Government agreed to establish four more multinational battlegroups, one of which is already stationed in Romania.

As of April 2022, there are 429 Romania’s servicemen on international missions. Largest deployment: 203 EUFOR Althea troops in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 101 NATO enhanced troops in Poland, and 54 KFOR troops in Kosovo. As of October 2022, 480 Romanian soldiers have participated in various missions and international operations outside Romania, of which 194 soldiers in 13 missions and training programs under the auspices of NATO (the most numerous participations: Poland 105 soldiers and Kosovo 65 soldiers), 262 in 9 missions and operations led by the EU (the most numerous participation: EUFOR-ALTHEA, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 213 soldiers) and 22 in two UN-led missions and operations.

Romanian National Security Strategy 2020-2024 identifies the Russian Federation as one of the threats to national security and stability of the political and security regional environment. Therefore, it was the policy of the Russian Federation in the Black Sea region that justified the beginning “of building robust deterrence and defence capabilities. This process is concurrent with the increase of our Armed Forces’ interoperability with the Allies, as well as with the strengthening of the institutional capacity to counter hybrid actions” (p.6). Romania also sees a threat in that “the attitude and actions of the Russian Federation carried out in violation of international law led to continued and extended divergences with a number of Western and NATO states and, represents a serious obstacle to identifying viable solutions for stability and predictability of the security environment” (p.19).

According to the Strategy, the following measures and actions respond to these threats:

- strengthening the Alliance’s containment and defence capabilities, especially on its eastern flank, through a North-South unitary approach;

- strengthening national defence and Romania’s active role on NATO’s eastern flank;

- enhancing the EU’s ability to work together and the US commitment to the security of the Black Sea region;

- providing sustainable solutions to ensure regional stabili ty;

- reaffirming the relevance of the Black Sea with its strategic importance in the regional security configuration;

- promoting regional cooperation on a wide range of humanitarian and economic issues.

Romania’s defence sector will benefit in 2023 from the allocation of 2.5% of GDP, according to the October 2022 decision of the Council of Security and National Defence (the CSAT) – an increase announced as early as March. Thus, according to the 2023 budget, approved on December 2022 by the Government and the Parliament, the Ministry of National Defence will receive a 35.3 billion lei budget – 52.3% more than in 2022. At the same time, the credits provided for in the budget of the Ministry of National Defence (MApN) amount to 68.2 billion lei, with about 30% more than in 2022.

So, for 2023, the budget will boost defence spending to 2.5% of GDP from the current 2.0% in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and raises budgets for intelligence services to counter hybrid attacks. “The strategic objective of the defence policy for the period of 2023-2026 is the modernization and adaptation of the Romanian Armed Forces to the specific risks and challenges of the current geopolitical context, as well as the consolidation of Romania’s profile as a relevant strategic partner at the level of NATO, the EU and within the strategic partnership with the US”, as it is mentioned in the budget sheet of the Ministry.

According to the military budget for 2023, the main ongoing programs (already contracted) are:

- High-range surface-to-air missile system HSAM – PATRIOT;

- Armoured personnel carrier (TBT 8X8);

- MLRS – HIMARS (Multiple Launch Rocket System) system;

- Air Force multi-role aircraft;

- System of mobile anti-ship missile launchers (SIML);

- Car transport platforms, multi-functional on wheels;

- Revitalization and modernization of IAR-99 aircraft;

- The main programs being signed or initiated:

- Multipurpose corvette;

- Continuation of equipping the Air Force with multi-role aircraft through the purchase of a package of 32 aircraft F-16 in M6.5.2 configuration, logistic support equipment and training services from Norwegian Air Force surplus;

- Security system and cyber defence;

- CBRN detection, warning, decontamination and protection (individual and collective) equipment and systems;

- Anti-aircraft missile system with very short range, portable – MANPAD;

- UAS systems (Bayraktar TB-2);

- Mobile electronic warfare system – SREM;

- Modernization of the OERLIKON Model GDF 103 anti-aircraft artillery system to the standard of anti-aircraft artillery system with CR AM capabilities;

- Main battle tank;

- Helicopters with surface combat capabilities type H215M;

- Minesweeper ships;

- Equipment required to equip forces for special operations;

While the increase in the military budget represents an important and effective measure, rare in NATO countries, one of the vulnerabilities is the systemic delays in the implementation of the main development programs, mainly those intended for the Navy (building four new multipurpose corvettes and upgrading the two existing frigates).

At the same time, the main effort of the Romanian defence and security system is aimed at strengthening the allied military infrastructure in the extended Black Sea region. The Black Sea region has a strategic significance for Romania and its allies, according to the National Defence Strategy for 2020-2024 (“The Black Sea region is of strategic interest to Romania and must be a secure and predictable area – essential for national, European and transatlantic security”) and the Alliance documents adopted (with a solid Romanian lobby in this regard) at the NATO Summit in Madrid in 2022 (the new NATO Strategic Concept).

For Romania, defining the Black Sea as a strategic area of interest for NATO reflects the fact that the Black Sea is at the centre of the aggressive action of Russia, with a high potential to deteriorate the security situation not only in the region but also in the entire Euro-Atlantic area. Therefore, NATO will continue to focus on this region as a priority, especially through consolidation and efficiency of the Allied presence on the Eastern Flank.

Economic Vulnerability

According to COMTRADE data, as of 2021, Russia was in the 19th place in the list of export countries for Romania, with a share of about 1.4% and a value of USD 1.21 billion, and the 7th country of import to Romania, with a share of 4.8% and a value of USD 5.62 billion. According to the Embassy of Romania in the Russian Federation, at the end of 2022, Russia ranked 42nd in the ranking of the countries of investors’ residence of companies with a foreign stake in Romania (600 companies, only about 0.25% of the total number). However, according to Europa Liberă’s analysis, this assessment does not reflect the real situation, and the presence of Russian capital is much greater because Russian investors operate in Romania mainly through intermediaries or subsidiaries in European countries.

Most experts note that the energy sector is one of the most important when assessing Romania’s economic cooperation and dependence on the Russian Federation. Compared to other states of Central and Eastern Europe, Romania’s energy dependence on Russia is significantly lower. Thanks to powerful local production, Romania meets about 80% of its natural gas needs, and only the remaining 20% is imported (for comparison, in Slovenia, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic, the share of own production is only about 3%, these countries import from 75% to almost 100 % of their needs). According to various data, the share of Romania’s natural gas imports from Russia is from 10% to 15,5%.

However, according to unofficial sources, in recent years, the share of Russian imports in Romania’s total gas consumption has increased, especially in the winter period, exceeding 20% in 2021. Instead, domestic production has been steadily declining since 1990. It is believed that Romanian gas reserves may be exhausted in 10-12 years at the current annual consumption. In this regard, Romania is working on alternative sources of production and supply.

At a meeting of the EU energy ministers in May 2022, minister of energy of Romania Virgil-Daniel Popescu noted that Romania has already identified other possible sources and routes for natural gas to reduce dependence on Russian imports. In particular, it is about the importance of functioning at maximum capacity of the Vertical Gas Corridor and the Trans-Balkan Gas Pipeline to ensure the gas supply from the liquefied natural gas terminals and Azerbaijan. Popescu also noted that although there were no problems with supply because Romania imports Russian gas through two intermediaries and did not have direct contracts with Gazprom, the country should properly prepare for the winter season, taking into account the precedent of Gazprom’s termination of gas supplies to Bulgaria and Poland.

In addition, Romania intensified work on gas extraction on the Black Sea shelf. In June 2022, the Romanian company Black Sea Oil & Gas (BSOG) announced the arrival of the first volumes to the country’s gas transportation system and its plans to secure annual gas production of 1 billion cubic meters in the next three year s (annual consumption is about 10-11 billion cubic meters).

The state also remains somewhat dependent on Russian crude oil. Romania imports about 70% of the crude oil it processes.

According to Eurostat, the share of crude oil imports from Russia is about 37% (or about 1/5 of total consumption). Crude oil imports from Russia to Romania increased to 323,000 tons in April from 272,000 tons in March 2022. But at the same time, the crude oil imports from Russia to Romania decreased to 79,000 tons in August from 259,000 tons in July of 2022, according to Eurostat.

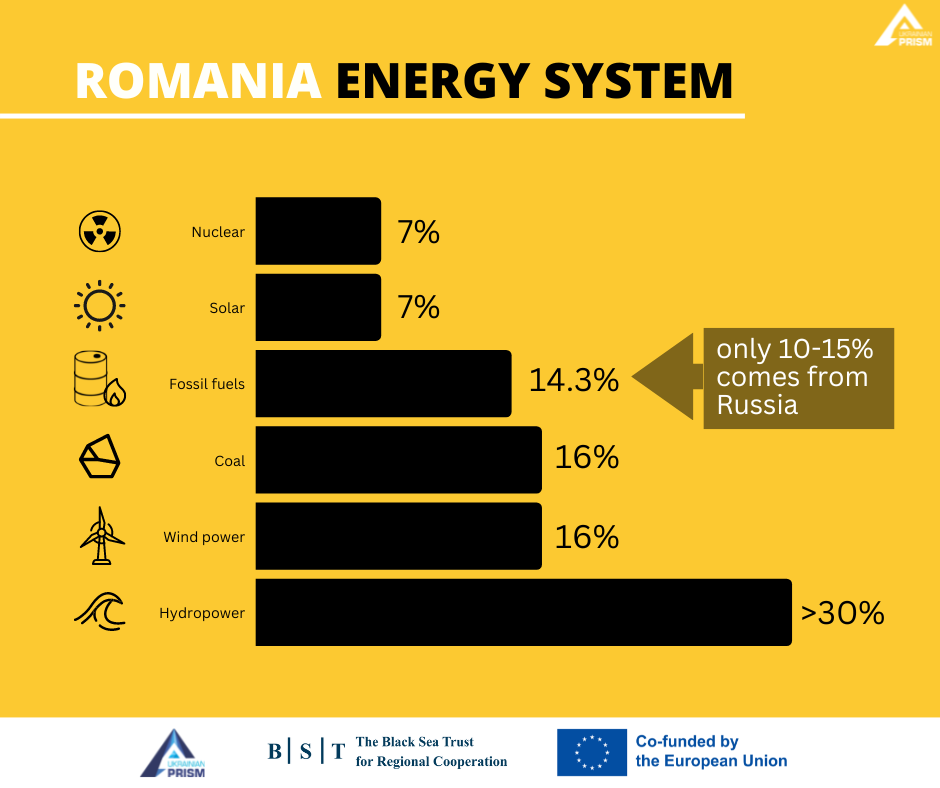

The Romanian government wants to transform the country’s energy infrastructure to attain energy independence, but experts warn there are still issues while environmental groups call for a bigger role for renewables. More than a third of Romania’s electricity production is provided by hydropower, followed by coal and wind power (approximately 16% each), fossil fuels 14.3%, and nuclear and solar energy contributions of just over 7% each. “Due to the country’s currently slow growth of renewable energy, projections show Romania will not meet the EU target of 32% renewables by 2030, even though their actual share in the energy mix is already 25%” – the 2022 Climate Change Performance Index shows, recommending policymakers to speed up policy ambition, as the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) includes phase-out for both lignite and hard coal by 2032.

At the end of 2022, Romania started providing electricity and natural gas to Moldova in an emergency procedure after Ukraine suspended energy exports to Chișinău because of the Russian shelling of its power plants. Romanian power producers sold electricity to Moldova at a capped price in October. In November-December, Romania provided between 80% and 90% of Moldova’s electricity needs.

Despite these successes, Romania’s external support capacity remains limited.

President Klaus Iohannis declared, at a meeting with his counterpart Maia Sandu, in November 2022, that “Romania is willing to continue supplying neighbouring Moldova with electricity as Russian shelling in Ukraine hits its energy supply, but insufficient interconnections are a challenge… Romanian-Moldovan interconnections are completely insufficient. Most of the power Romania is offering passes through Ukraine”.

Informational Vulnerability

Romanian society is not vulnerable to Russian propaganda. There are several reasons for this: weak cultural and economic ties with Russia, a language barrier, as well as a traditionally negative attitude towards Russia because the people of Romania consider the Russian Federation to be the main threat to national security.

According to a study conducted by INSCOP on May 16-21, 2022, 71.2% of Romanians believe that the Russian Federation is responsible for the war in Ukraine. 87.3% of Romanians believe that Russian political leaders should be found guilty of war crimes committed by the Russian military in Ukraine, and strengthening NATO’s eastern flank by transferring additional weapons to Romania is supported by 65% of Romanians. On issues fundamental to Romanian statehood, as of July 7, 83% of residents believed that their country should follow the West in matters involving political and military alliance.

Even before the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Federation, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Romanian government began to fight the spread of fakes and disinformation, passing a series of decrees that allowed the authorities to issue orders to remove articles and websites accused of spreading “false information” about the pandemic. The reason for this decision was the lack of media literacy among the population and the unprofessionalism of the mass media in general, which allowed the Kremlin to achieve its goals by undermining trust in European institutions. After February 24, the unpopular among the Romanian population, Russia Today and Sputnik, were blocked, leaving Russia without its two main media resources in the country. Our southern neighbour also blocked a number of other potentially dangerous websites, including: profitsmall.com, yourincome.site, citeșteșitu.com, cloudx.ro.

There are no Russian TV channels or other media directly owned by Russia and operating in Romania today, which is a consequence of the blocking of RT and Sputnik mentioned above. Since the most popular source of information in Romania is television, the coverage of which is 77%, the probability of delivering Kremlin narratives is minimal. Facebook is the second most popular resource, reaching 64%. Despite the popularity of this social network among the country’s residents, pro-Russian groups and pages are detached from the general canvas of the country’s information field. The Russian strategy in Romania is reduced to pedalling narratives designed to undermine confidence in Romanian democracy and Bucharest’s Euro-Atlantic partners. The third most popular information resources are websites with news – 58%. A study conducted by specialists of the Political Capital strategic research and consulting institute shows that the number of pro-Kremlin sites, including napocanews.ro, activenews.ro, flux24.ro, and others is limited, and their reach is very modest.

The situation with pro-Russian political fo rces is similar. There are no openly pro-Russian parties in Romania, and the radical right-wing discourse is much less widespread than in Hungary, for example.

The only relatively popular right-wing force is the Alliance for the Unification of Romanians, a nationalist opposition party with little representation in parliament – 9.1%. As a tool of information influence, the party actively uses Facebook, to which it owes its success. The number of followers on the official page in this social network exceeds 150 thousand people. George Simion, the leader of the Alliance for the Unification of Romanians, is even more popular: he is followed by 1.2 million people. The level of coverage is quite significant: thousands of people share and comment on each post. The total number of subscribers of regional branches of the party is more than 300 thousand people. Although the Alliance actively promotes anti-European narratives that partially correspond to the informational agenda of the Kremlin, Moscow did not officially support the party, and its leader called the Russian Federation the biggest threat to Romania. Another information channel from the Alliance for the Unification of Romanians is the Revista Rost website, which was initiated by party co-founder Claudio Tarzio. This resource represents the views of its founder and its political power, therefore Revista Rost is dominated by anti-European, but not pro-Kremlin discourse.

In the context of this study, it is also worth paying attention to Russian organizations that act in the interests of the Kremlin or are financed by it on the territory of Romania. Such is, for example, the Coordinating Council of Russian Compatriots in Romania (Координационный совет россический соотечественников в Руманиия), which is closely connected with Russian state structures, in particular the Embassy of the Russian Federation in Romania and the Russian House in Romania. The latter is a branch of Rossotrudnichestvo.

Also, the Chamber of Economic and Cultural Cooperation between Romania and Russia operates on the territory of the state and provides consulting services through experts in various fields, including banking, investment, legal, etc. Although this organization is formally non-governmental, it promotes Russian interests in the country of its establishment, in particular, on its Facebook page. Despite their activities, these institutions do not have a wide information influence because their main audience is primarily the Russian diaspora in Romania (which is, in accordance with the latest representative census, is around 24 000 people).

In conclusion, it is worth saying that Romanian soil is not too favourable for the germination of Russian narratives, except for certain social groups. Potentially vulnerable are those who support the revisionist views of certain forces and members of the fearful generation who feel nostalgic for the communist past. Immunity to Kremlin propaganda is facilitated by: the negative attitude of Romanians towards the Russian Federation, the unpopularity of revisionist and anti-Western discourse, a high level of support for membership in NATO and the EU, the absence of pronounced pro-Russian parties and a narrow range of audiences for information resources and organizations that promote Russian interests. The opportunities of the Russian Federation are very limited, not so much due to the blocking of Russian media as due to the historical memory of Romanians and their views regarding the future of their country. All that left Russia with an option to present its narratives in a very dosed manner, concentrating rather on efforts to undermine confidence in Bucharest’s Euro-Atlantic course.

Cases of Successful Operations to Detect and Limit Russian Influence and Manipulation

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine forced the EU to reconsider its policy regarding Russian information resources. This also applies to Romania, which faced the same task. Romania blocked the Russian media RT and Sputnik, which were the main mouthpieces of Kremlin propaganda, as well as a number of Romanian outlets. Despite these actions, opposition to Russian narratives is generally rather sluggish. In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, Romania’s intelligence service, which is also tasked with combating disinformation, failed to cope with the influx of Russian propaganda, causing the vaccination campaign to fail because as of O ctober 2021, only 36.3% of the population received at least one dose of the vaccine. Corneliu Bjola, a professor of diplomatic studies at the University of Oxford, believes that the Romanian intelligence service was not always competent and sometimes showed tacit complicity.

Although pro-Russian and radical right-wing discourses are not very popular in Romania, there is still a single right-wing force represented in the parliament – the Alliance for the Unification of Romanians. On March 31, 2022, then parliamentarians from this party, Diana Shoshoake, Mihai Laska and Francis Toba, who were expelled from the Alliance for the Unification of Romanians due to differences with the leader of the political force, George Simion, met with the Russian ambassador in Bucharest, Valery Kuzmin, presenting a proposal for the so-called “position” of Romania’s neutrality in Russian-Ukrainian war. Together with the three politicians named above, there was also a member of the ruling Social Democratic Party, Dumitru Koarne. The latter was expelled from the party because he “crossed the red line by conducting a dialogue with the aggressor state.” Francis Toba was expelled from the defence committee, and there was no information about sanctions against Laska and Shoshoake.

Regarding Russian diplomats in Romania, in April 2022, the authorities of this country decided to declare ten persons who worked at the embassy as persona non grata, believing that their activities and actions contradicted the provisions of the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. The foreign policy department did not provide any other clarifications.

In addition, Romanian organizations regularly conduct investigations related to informational influences. Most investigations are devoted to the already mentioned political party – Alliance for the Unification of Romanians. Researchers say that the party’s Facebook groups spread narratives that resonate with Russian ones and are designed to undermine confidence in European values and authorities in Bucharest. Romanian investigators are al so paying attention to Russia’s influence in Moldova, as due to the language share and close connections, it can have a spill-over effect. We are talking about the study of the impact of Russian propaganda on the media space of Moldova, the public’s perception of mass media and the consumption of media content.

As for experts, Russian influences are studied and analysed, among others, by Ileana Racheru, Oana Popescu, Oana Despa, Bianca Alba, Radu Carp, Marius Diaconescu, Valentin Naumescu, Elena Calistru, Angela Grămadă, Laura Burtan and others. It is also worth paying attention to research centres that study the Russian Federation. Such are the Romanian Centre for Russian Studies at the University of Bucharest, Veridica and others. Special mention should be made of the Veridica project team, which is engaged in refuting Russian fakes and disinformation in Romania.

In conclusion, we can stress that blocking the two main Russian media resources in Romania shifted the role of the mouthpiece of Kremlin propaganda to the Russian Federation embassy in Bucharest. Therefore, it is not surprising that in May 2022, the amb assador of the Russian Federation was summoned to the Romanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs because of an article titled “About NATO’s barking at Russia’s borders and the main source of disinformation in the world.”

The Threat of Reflexive Control Operations

As noted in the previous parts of the work, Romania is sufficiently stable in the matter of resistance to negative Russian informational influence. Timely interruption of their broadcast channels and work with the population and the political opposition not only forced pro-Russian information influences to move into the shadows compared to the national media but also to move to work with rather marginal and specific topics. The general profile for the work of Russian elements of hybrid warfare is extremely disadvantageous and complex, which minimizes the possibility of applying reflexive control tools.

Despite the fairly optimistic picture of resistance to Russian informational influences, it is also worth pointing out those areas where the Russians can still have partial success in applying their own influence measures. Clarification: in the format of this study, we will consider the possibility of destabilization of the information space of the stat e and marginal influence on the part of its policy as a partial success. These areas of potential Russian activity are the following:

1.Energy

Although Romania is only 10-15% dependent on Russian fuel resources, Russia possesses effective tools for political and technical provocations related to the supply of these resources. The experience of other countries in the region shows that even with a minor overall impact of these specific deliveries, Moscow still has the opportunity to blackmail them by not fulfilling them and to use the technical features of the process to threaten unpredictable man-made consequences. Such a crisis will obviously affect the decision-making process in the Romanian establishment.

2. Black Sea militarisation

The Russian Federation’s aggression against Ukraine also involved a massive militarization of the Black Sea on the part of the Russian Federation.

The constant presence of warships, the mining of the water area, as well as the situation with the shelling of Romanian ships really became a matter of direct military threat to the economy and the citizens of Romania. Russia can use this leverage in its interests. Russia can also involve provocations against the ships coming to the Romanian ports or limiting navigation at the Danube entrance. Even if the latest became less possible after they lost control over Snake island, the constant shelling from the ships against the Ukrainian south can lead to accidents and raise risks for the Romanian coast as well.

3.Toxic political topics

The Russian information machine is used to working with toxic and complex topics, which in one way or another, can divide the society of the target country. It was for these reasons, as it was shown in the study, that the Russians at one-time bet on the Alliance for the Unification of Romanians because it was their rhetoric that could be effectively used to fragment certain political and social groups and cause both domestic political and regional instability. Of course, one cannot discount the scenario that Mo scow may try to repeat this model if necessary.

Recommendations

Given Romania’s existing strengths and potentially dangerous crisis situations that the Russian Federation may create, it is possible to propose the following programs and measures to strengthen Romania’s resistance:

- Expanding existing security programs with NATO by:

1.1. Scaling of infrastructure facilities and capacities of the Alliance on the territory of Romania; the development of the military mobility infrastructure on the territory of Romania;

1.2. Strengthening of the Air Force Group of the Alliance on the territory of Romania;

1.3. Broader involvement of the Romanian military in NATO ground forces (primarily – in the mobile response group);

1.4 Accelerating the equipment programs of the army, especially those regarding the Naval Forces (the Multipurpose Corvette Program and the modernization of the frigates).

- Strengthening the informational resistance of the state by:

2.1. Improving cooperation between the state and civil society;

2.2. Further evolut ion of legislation in the field of combating disinformation, taking into account the position of experts and civil society;

2.3. Continuation of blocking and sanctioning against Russian propaganda media.

In both spheres, it will be extremely useful to involve Ukrainian experts – both from the state and non-state sectors – to strengthen the expert and resource component of the relevant measures. It is Ukrainian experts in the field of security and information warfare who currently have unique experience in resisting Russian aggression.

Also, the specificities of Russian propaganda in Romania, Ukraine, and the Republic of Moldova require closer cooperation between state and private platforms in the three countries in the field of exchange of experience and best practices for combating Russian propaganda and disinformation.

It is also recommended that current opportunities to provide substantial national analytical input to the future development US Black Sea Strategy be exploited.

Maintaining and amplifying Romania’s lobby for an increased military, political and economic presence of NATO and the EU in the region can have substantial effects on the security of th e entire region, including Romania.

Closer cooperation between the naval forces of NATO countries in the Black Sea is desirable, based on multiple cooperation programs and initiatives.

This publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union and the Black Sea Trust for Regional Cooperation. Its contents are the sole responsibility of Foreign Policy Council “Ukrainian Prism” and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union and the Black Sea Trust for Regional Cooperation.