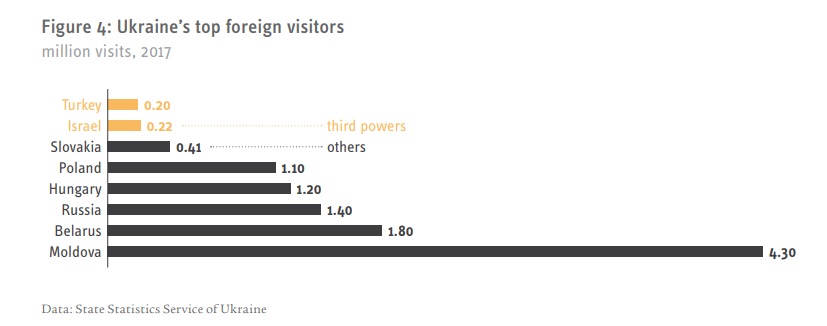

Introduction For the last four years, Ukrainian foreign policy has been wholly focused on the European and Euro-Atlantic dimensions. This has often negatively influenced its relations with other countries, where it has failed to demonstrate a strategic vision and proactive approach. While cooperation with the US and resistance to Russian aggression have ranked high on its list of priorities, Ukrainian interaction with such regions as the Middle East or China has been unsystematic and lacking in coherence. For almost a decade, Ukraine’s relations with third countries were either essentially reactive or dictated by the policies of its main strategic partners. As a result, by 2016, Ukraine had not substantively developed bilateral relations with many countries. While Ukraine’s previous approach of pursuing a dual foreign policy orientation (reaching out to both the EU and Russia) gave way to a drive towards European integration, relations with third countries were formulated separately and reflected several basic goals and motivations: the economisation of foreign policy, energy diversification and, since 2014, the quest for support in the face of Russia’s attempted annexation of Crimea and illegal actions in Eastern Ukraine, human rights violations committed against Crimean Tatars and ethnic Ukrainians in Crimea, and the restoration of Ukraine’s territorial integrity. Turkey In the last few years, Turkey has emerged as one of Ukraine’s leading partners. Although in the past, it had always been an important trade and economic partner, developments in the political and security sphere since 2014 have significantly upscaled the level of relations between the two countries. Despite ups and downs in EU-Turkey and Russia-Turkey relations, in which Ukraine at times risked becoming Third powers in Europe’s east a hostage to their political agendas, the two countries have managed to increase their cooperation. Back in 2014, Ankara actively supported the Crimean Tatars, but was not very vocal about Moscow’s annexation of Crimea,1 and did not want to join European sanctions against Russia. This cautious and restrained position might be explained by the long-term vision shared by both Ankara and Moscow that the Black Sea belongs to their natural sphere of influence: Turkey is aware that spoiling relations with Russia would lead to greater EU and NATO involvement in regional affairs as well as jeopardising trade and economic relations between Moscow and Ankara (in particular energy cooperation, tourism and agriculture, and projects for the construction of new nuclear plants). However, the situation changed dramatically at the end of 2015, when the downing of a Russian military warplane by the Turkish airforce led to a severe deterioration in Russia-Turkey relations. Ukraine availed of the opportunity to enhance political, economic and military dialogue with Turkey, and this resulted in the signing of a substantial number of agreements and contracts. These included: a Joint Declaration following the Fifth Meeting of the High-Level Strategic Council between Ukraine and Turkey, where special attention was paid to security and defence cooperation, as well as to the predicament of the Crimean Tatars in the wake of Russia’s annexation of Crimea,1 and an agreement between the governments of Ukraine and the Turkish Republic providing for the free transfer of surplus military property (including battle suits) from the Turkish armed forces to the Ukrainian military (March 2016). A Memorandum between the Ministry of Education of Ukraine and the Higher Education Council of Turkey was also signed, allowing for the joint training of specialists in strategic spheres, such as aviation, nuclear energy, the space industry, etc (March 2017). It is important to note that even after relations between Moscow and Ankara improved in summer 2016, the thaw in Russian-Turkish relations did not have a concomitant negative impact on the increasing cooperation between Ukraine and Turkey.2 Today, the range of projects on the bilateral agenda is quite broad and varies from creating joint enterprises in the defence and space industry sectors to common use of gas pipeline infrastructure, cooperation in the nuclear energy sphere, conducting joint naval and military exercises, exchanging information and sharing experience in countering terrorism.3 In 2015, the two presidents announced their goal to reach $10 billion trade turnover by 2023. While 2017 demonstrated a 20% increase in trade, the signing of a free trade area agreement between the two states has remained a key priority.4 While the initial goal was to complete the agreement by 2016, consultations are still taking place, with agricultural quotas among several difficult issues yet to be resolved in the negotiations, which are however entering the home stretch. Ukraine already enjoyed a visa-free regime with Turkey, and since summer 2017, citizens of both countries can cross each other’s borders using internal biometric IDs. This will not dramatically influence tourist numbers (currently around one million Ukrainians visit Turkey annually), but, nevertheless, it is further evidence of the high level of trust that has been built up between the states. People-to-people contacts have also intensified due to the Crimean Tatars issue, where Turkey plays a significant role. The report entitled ‘The Situation of Crimean Tatars since the Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation’, released in June 2015 by an unofficial delegation of Turkish members of parliament,5 attracted a lot of attention as no other delegations was allowed to visit Crimea. Ankara’s assistance in securing the release of two prominent members of the Crimean Tatars’ Mejlis from a Russian prison in October 2017, demonstrated both in Ukraine and in Turkey (where 4 million Crimean Tatars live) the positive role that Turkey can play in this context.

In 2016-2017, when relations between the two countries deepened significantly, Ukraine found itself faced with the difficult prospect of taking sides in the developing crisis in EU-Turkish relations. As Ukraine needs Turkey as a reliable security partner in the Black Sea region and as an ally in protecting Crimean Tatars’ rights, it seems likely that Kyiv will refrain from getting involved in any rows between the EU and Turkey for as long as possible.

China

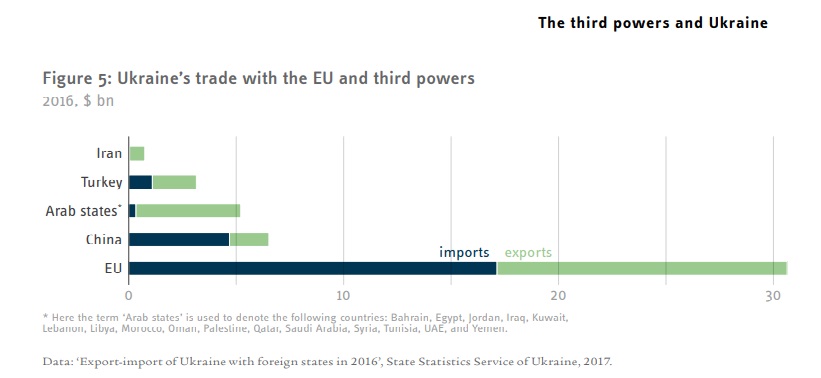

China has always remained a predominantly economic partner for Ukraine. In the crisis in and around Ukraine, Beijing has also remained aloof, preferring not to intervene in regions beyond its own sphere of interest in Asia and not to jeopardise relations with Moscow. Therefore, in March 2014, China abstained during the UN General Assembly vote on the territorial integrity of Ukraine, and in 2016 voted against the UN General Assembly resolution on human rights violations in Crimea. Despite the fact that at all bilateral meetings the Chinese have officially confirmed respect for the territorial integrity of Ukraine, there have been incidents such as the case of the Chinese company Jiangsu Hengtong Power Systems, which violated laws by providing high-voltage energy cables and staff for the construction of an underwater ‘power bridge’ between Russia and Crimea in 2015. As a result, a criminal investigation has been launched in Ukraine against the company and its personnel,6 but this has not impacted on the political dialogue between the states. After some intensification of relations in 2015, political and interagency dialogue with China entered a long-term hiatus. Only a significant bilateral interest in business and trade opportunities and the potentially important geostrategic position of Ukraine in the One Belt One Road project keep these relations from stagnating entirely.7 In the case of the Belt and Road project, the interests of Ukraine and the EU coincide. At the same time, Beijing is hesitating to invite Ukraine to join in the 16+1 format (Eastern European states + China). This is for at least two reasons: a desire to concentrate on developing relations with the EU member states, and the perception that Ukraine has recently attached more value to its relations with Japan, due to Japan’s readiness to provide Ukraine with political, humanitarian, technical and economic assistance, while China has preferred to engage in economic relations exclusively. It is also noteworthy that both Russia and Belarus are actively promoting themselves as main hubs and transit points for the One Belt One Road (on the alternative route bypassing Ukraine). However, in this situation China, despite its avowedly apolitical approach to the project, is carefully considering the risks due to the sanctions that the EU imposed against Russia following the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. Moscow has already tried to introduce a land blockade for transit goods from Ukraine to China, which was partially overcome by the introduction of the multimodal container train project on the Ukraine-Georgia-Azerbaijan-KazakhstanChina route.8

Both Beijing and Kyiv have a strong interest in cooperation in the agriculture, transport, and trade and investment spheres, but are hesitating to intensify such collaboration. Since 2014, China has been seen in Ukraine as a possible substitute for Russia, in terms of big infrastructural projects and for cooperation in the agricultural sphere. Meanwhile in 2015 China was among Ukraine’s five biggest trade partners, accounting for approximately 33% of Ukrainian exports to the Asia-Pacific region, and 57% of imports from the region.9 In terms of general trade turnover, China accounted for 8.6%. In 2013, it was just 3.9%; however, Ukraine’s overall trade turnover with other countries in absolute numbers was twice as big. The main exports from Ukraine are ore (32%), grain (30%), fats and oils (26%), whereas Ukraine’s main imports from China are electrical equipment (22%), and boilers and machinery (17%).10 Kyiv’s hopes of attracting extensive Chinese investment have remained unfulfilled as the Chinese share in total Ukrainian FDI is less than 1%. Military cooperation is also on the agenda, with China in certain years ranking as the third-biggest importer of Ukrainian weapons, being mostly interested in engines and aircraft (especially a deal on manufacturing the Antonov An-225 Mriya, the biggest carrier in the world).11

Arab states

While Ukraine has had a long history of contacts with many Arab states (since Soviet times), it has never prioritised these countries in its foreign policy. Never having formulated a clear Middle East policy, Ukraine also found itself in competition with Russia in the 1990s-2000s. Ukraine was seen as a new state without a historical connection to the region, but at the same time its products, equipment and universities were well-known in many Arab states. Russia, in its turn, had long-term relations with the political elites in many Arab states, although the dominance of the Soviet past has sometimes proved to be a complicating factor. So Russia and Ukraine have become competitors in the Middle Eastern military equipment and arms sales market, as well as for big infrastructural projects and energy resources. Ukraine’s two-year involvement in Iraq (2003-2005) did not bring significant benefits to the country, apart from raising its political profile. Having contributed the fourthlargest contingent of troops (up to 1,600 military) to the international peacekeeping operation, the Ukrainian authorities expected new military contracts and involvement in the reconstruction projects in Iraq to follow. Even more importantly, they hoped that this would lead to an improvement in Ukraine-US relations (previously overshadowed by several scandals, including the unproven allegation that Ukraine sold a sophisticated Kolchuga radar system to Iraq). However, Kyiv’s high expectations of new contracts have not been fulfilled, with only a few signed, and one of the biggest having failed. This was a deal concluded in late 2009, whereby Ukraine would provide Iraq with $2.5 billion worth of weapons and military equipment.12 However, problems began to emerge as early as 2011,13 amid revelations of Ukrainian corruption, the sabotage efforts of some pro-Russian Ukrainian top officials, competition between Russia and Ukraine for the delivery of BTR-4 armoured personnel carriers (APCs)14 and allegations of a Russian smear campaign aimed at discrediting Ukraine. Being able to pursue a policy based on economic pragmatism without any political conditions attached is what distinguishes Ukrainian relations with the Arab states from its relations with Europe. While before the Arab Spring, Egypt, Libya, Iraq and Lebanon featured among Ukraine’s main partners, Ukraine subsequently shifted its attention to the Gulf monarchies. For example, no meetings of the joint UkrainianEgyptian Intergovernmental Commission on Economic and Scientific-Technical Cooperation have taken place since 2010. Due to the security situation, the number of Ukrainian tourists visiting Egypt, for example, has dropped, while agricultural products and black metal have remained Ukraine’s main export goods. Around $2 billion of the trade turnover with Egypt in 2016 demonstrated a significant positive balance for Ukraine.15 Arms and aircraft sales, investments and energy links, and agriculture have always been among the key areas for cooperation with Gulf States. In November 2017, a new impetus was given to this cooperation by the visit of the President of Ukraine to Saudi Arabia (the first such visit in 14 years) and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). As a result, Ukraine and the UAE agreed to introduce a visa-free regime, and step up cooperation in the space industry sector,16 while Ukraine and Saudi Arabia agreed on participation in privatisation projects, Saudi investments in agriculture, and cooperation in the information and educational spheres.17 Aircraft manufacturing is a key aspect of the military-technical cooperation with Saudi Arabia, where Ukraine’s Antonov aircraft-manufacturing company together with Saudi KACST and Taqnia Aeronautics agreed on joint production of An-132D (initially in Ukraine with a later phase of manufacturing to be moved to Saudi Arabia). The new priorities set for cooperation with the Gulf States are the space industry, military-technical cooperation, aircraft manufacturing, and investments, especially in the agriculture and energy sectors. Moreover, in the context of these agreements both Saudi Arabia and the UAE pledged support to the Crimean Tatars and the territorial integrity of Ukraine. The issue of Islamic networks is less of a preoccupation for Ukraine than is the case in Europe. While naming the so-called Islamic State as a threat to international security in its National Security Strategy, Ukraine is not involved in international projects countering it, inter alia because Ukraine has not been confronted with the influx of migrants from the Middle East and North Africa that the EU has experienced in the past few years. Syria is the only security issue that features in the Ukrainian political discourse and negotiations between Ukraine and European leaders, but this is mostly in the context of Russia’s involvement in Syria and parallels between the Russian military intervention in Donbass and Syria. Here cooperation is possible, as the Ukrainian security forces and intelligence services possess experience and information that can be useful for planning future European activities in Syria. Recently a report of the Security Services of Ukraine was presented in Brussels, giving details of crimes committed by Russian private military companies in Donbass and Syria.18

Iran

Iran has never featured prominently on the Ukrainian foreign policy agenda. Back in 1998, Ukraine cancelled its participation in the construction of the Bushehr nuclear plant (under US pressure), thereby opening the door for Russian involvement, and closing the door on what would have been the biggest Ukrainian project in the region. Since then, Ukraine has mostly fallen in with American policy towards Iran or correlated it with its own nuclear-free status and non-proliferation policy. As a result, it was only in 2016, after the lifting of international sanctions, that Ukraine resumed its cooperation with Iran, including restarting the Intergovernmental UkrainianIranian Joint Commission on Economic and Trade Cooperation, which had been frozen for 12 years. Ukraine is mostly interested in economic and energy cooperation with Iran. Here Ukraine and the EU are neither competitors nor partners as the long period of sanctions left a vacuum that still needs to be filled. Despite the Russian-Iranian tandem in the Syrian crisis, Iran chose a more careful position vis-à-vis Russia’s military intervention in Ukraine. In March 2014 the Iranian representative was absent from the vote in the UN General Assembly backing the territorial integrity of Ukraine and not recognising any change in the status of Crimea, but in 2016, after Kyiv lifted sanctions against Iran, Tehran officially expressed support for the territorial integrity of Ukraine.19 In the present situation where Donald Trump is again calling for Iran to be internationally isolated, while the EU will most probably continue with the policy of engagement, Ukraine will face a difficult choice. Considering its current economic interests, Kyiv will most probably align with the European position. The main argument in this case will be Iran’s stance vis-à-vis its nuclear programme, as for Ukraine this issue was the most important in terms of the application of sanctions. Conclusion In the political sphere, Ukraine’s relations with third countries generally have little impact on EU-Ukrainian cooperation, due to the ultimate goal of the European integration of Ukraine and the hopes that Kyiv has invested in the potential of the Association Agreement. Chinese investments in the country can sometimes compete with those of the EU; however, Beijing is not aspiring to a political or security involvement, so spheres of interest can be shared with the EU. Cooperation with Iran and the Arab states is too marginal at the current stage to influence Ukraine’s foreign policy agenda, despite the latest agreements and initiatives with Saudi Arabia and the UAE. None of the third players that are engaged with Ukraine, with the exception of Russia, is trying to undermine the leading role of the EU in Ukrainian politics. While economic projects may become an issue of competition in the future, none of the regional actors whose role has been analysed here have any aspirations to influence in the political sphere. Internal political dynamics and political competition are likely to be the biggest factors preventing closer EU cooperation with Ukraine. From Kyiv’s point of view, intensified cooperation with other regions is instrumental to its strategy of diversification of its economic and energy policies, expanding the geography of Ukrainian exports, as well as a necessity to build strong international support to counter Russia’s annexation of Crimea and aggressive actions in Eastern Ukraine.